Picture the scene.

A beach heaving with bodies. Sunbeds racked up alongside the pool. High tower blocks of rooms, one packed on top of another. Tourists clustered round the buffet. All in a complex gated off from the local community.

A classic example of the kind of travel that devastates the environment and gives nothing back to local communities? Hell for those of us who like to think of ourselves as responsible travelers?

Think again. According to experts in sustainable tourism, the all-inclusive package holiday could be the sustainable vacation of the future.

“In the past, package holidays – particularly all-inclusive – have been regarded as the least sustainable way to travel,” says Justin Francis, CEO of Responsible Travel.

But he says that all-inclusive resorts have the “potential” to be a highly sustainable way to accommodate mass tourism.

“Done the right way, there’s a real need for it,” he says.

Jeremy Sampson, CEO of the UK-based Travel Foundation, agrees. “I don’t think there’s a reality where everyone just goes to ecotourism lodges,” he says. “It’s not really feasible and doesn’t help destinations shift the pressure in other ways.

“In most cases, the infrastructure in ‘precious’ places isn’t that prepared, so there’s absolutely a place for mass tourism – we just have to think about doing it a lot better.”

So could a pile-‘em-high, cram-the-sunbeds-in beach holiday really be the green way to travel we’ve all been looking for?

Transport is already moving the right way

On one level, package holidays are already doing pretty well – and that’s the transport to the destination. Package tour operators tend to use budget flights or their own planes, and legacy airlines tend to have older fleets than budget airlines. Delta’s planes have an average age of 15.1 years, according to Airfleets.net. Austrian’s average 15.4 years, and British Airways’ average 13.8 years – although its fleet of 747s, which it plans to gradually phase out, has an average age of 22.5 years.

Norwegian Air’s fleet, in contrast, has an average age of 2.8 years, according to the airline’s website.

The difference? Newer planes tend to be more fuel-efficient. Budget airlines also tend to cram more passengers in, not least by axing space-greedy business class seats.

“Flying on a packed easyJet plane that’s three or four years old gives you a lower carbon footprint than a three-quarters-full 20-year-old plane with another airline,” says Francis.

At the other end of the flight, package holidays tend to bung guests into a coach or bus to transport them to their hotels. After trains, buses are the most environmentally efficient mode of mass transport.

The current situation: could do better

Unfortunately, as things stand, that’s pretty much as green as all-inclusive holidays get. Once in the compound, guests tend to stay there. They eat in-house, since they’ve already paid for it, so they rarely venture out to locally owned restaurants.

“It’s not as simple as the carbon from the flight,” says Jeremy Sampson.

“Some negative impacts are related to where they shop, the kind of transportation they take, where the food is sourced, what kind of food it is, and the quantity.

“It’s important that people start to look at the whole chain of activities they’re involved in.”

Staying by the pool, they’re unlikely to go out and visit cultural centers or buy from local artisans, either. The local community suffers the effects on infrastructure from tourism but sees no money from it.

Food in resorts tends to be in the form of buffets – a quick and easy way to cater to the high turnover of guests. But this leads to huge food wastage. What’s more, an insistence on international food at the buffet – rather than local dishes – means that ingredients are flown in from all over the world, increasing the carbon footprint.

In fact, a report by journal Nature Climate Change in 2018 found that shopping and food are “significant” contributors to your travel footprint, in some cases being as impactful as your journey to the destination.

Why we need package holidays

Tourist numbers are already at record highs. There were 1.4 billion leisure arrivals worldwide in 2018, according to the World Tourism Organization – up 6% on 2017, and with a 3-4% increase predicted for 2019.

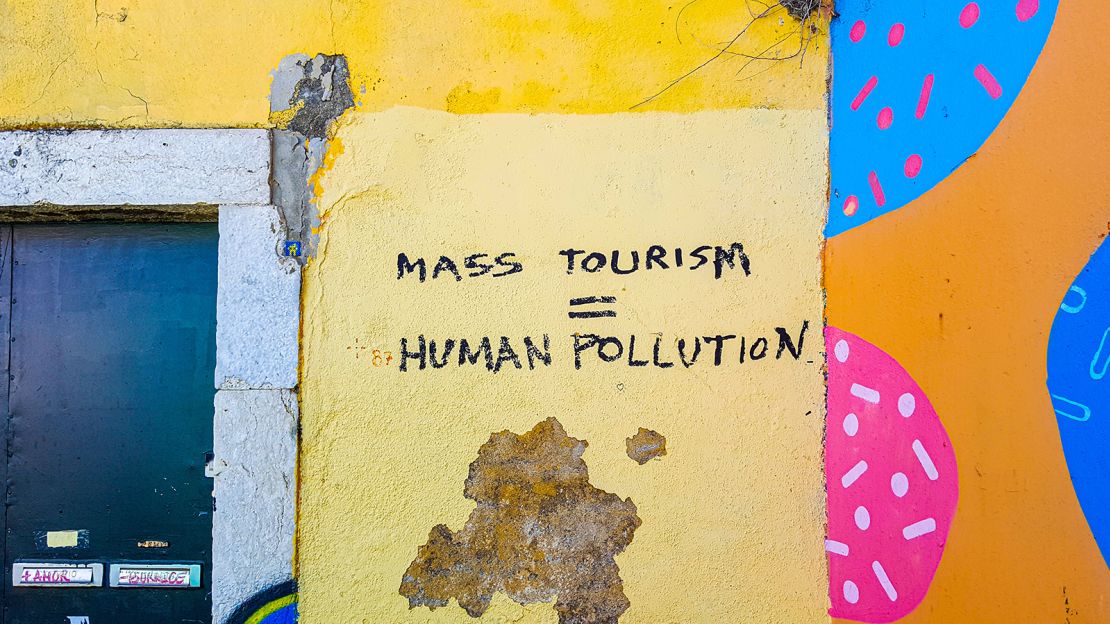

Yet destinations cannot cope. Overtourism risks ruining destinations from Venice to Bali. Amsterdam’s 867,000 residents are dwarfed by the 18 million visitors who descend on the city each year.

Inhabitants of popular cities from Barcelona to Lisbon report being squeezed out of their homes as developers buy up real estate in order to rent it out on Airbnb.

So although the idea of tourists enclosed in a compound away from locals has traditionally been frowned on, it’s time to look at it a little differently, says Justin Francis.

“Residents are saying that having too many tourists in the places they live is degrading the quality of their lives,” he says. “The places they want to rent or buy are being taken out of the market, the price of living is going up, and the streets are becoming overcrowded.

“There’s noise, disturbance and bad behavior.

“All-inclusive models don’t have much impact on local residents because there are no local residents. It was previously thought that keeping tourists in a compound was a bad thing, but it eliminates potential issues in destinations where locals are trying to live alongside large numbers of tourists.”

What’s more, a significant number of vacationers will always want to do little more than fly and flop. “All inclusives can make a lot of sense for some destinations and allow for the kind of visitor who just wants to relax on the beach and have things prepared for them,” says Sampson.

And with tourist numbers rising, current destinations simply don’t have the infrastructure to accommodate everyone who wants to travel.

This is where standalone resorts for package holidaymakers can save the day.

“We need to take the pressure off crowded destinations,” says Francis. “Places like Disneyland or all-inclusive resorts could be part of the solution.”

That is, if they can change their behavior.

Eating local

The traditional all-inclusive model – where almost everything is sourced from outside, and guests plow little money into the local economy – doesn’t have to be the future, according to Justin Francis. “There isn’t any reason why hotels couldn’t buy food locally,” he says. If they did, they’d not only put money into the local community, but also slash the carbon footprint of the food served in resorts.

Some progress is already being made toward this. Ikos Resorts, which has three all-inclusive properties in Greece and one in Marbella, sources 60% of its produce locally and works with local suppliers to produce its own-brand organic olive oil, wine and honey.

Crucially, it includes local restaurants in its all-inclusive program. All guests have to do is book in advance.

On a wider scale, pilot projects are being overseen in popular destinations, usually as a result of private-public partnerships.

The Travel Foundation works with large tour operators and resorts around the world to integrate local communities into mass tourism. Their small-scale partnership projects get hotels and resorts sourcing products from local suppliers, trickling money into the local community.

Its Taste of Fethiye project, launched in 2010 on Turkey’s Turquoise Coast, matched 40 local farmers with up to 24 resorts across Fethiye, supplying them with up to 85% of their produce. Hotels marketed the project to guests as a plus point, and put on special “local food nights” and craft fairs, where tourists were able to buy direct from artisans.

Today – three years after the project officially ended, and the Travel Foundation’s support finished – it’s still going strong, with 15 hotels working with the new local organizers.

In Mexico’s Riviera Maya, the Travel Foundation partnered with tour operators including Tui, Thomas Cook and Karisma Hotels to place locally made jams and honey products in hotel shops.

Jam sales rocketed from £300 ($372) a year to £16,000 ($19,834), helping 69 members of the Mayan community. The honey producers made £17,000 ($21,074) in sales to just five businesses in their first three years of trading.

And the Travel Foundation has used what it learned from Taste of Fethiye for its current three-year Flavors from the Fields project in Turkey’s Muğla region, run in conjunction with the Tui Care Foundation. In an area where hotels typically source less than 15% of their produce locally, and agriculture is rapidly declining, they’re again bringing local growers and hotel kitchens together.

What’s more, having seen that over half of local producers don’t add value by processing what they grow – by turning fresh olives into oil or bottling them, for example – the project is helping growers make more money out of their produce, developing a range of goods to be sold in hotel shops, amongst other places.

“We wanted to see if that was a better way of spreading out the economic benefits of tourism,” says the Travel Foundation’s head of communications, Ben Lynam.

Fifty hotels and 150 farming families are already taking part in the scheme, with 800,000 tourists expected to get the chance to eat locally sourced food while on holiday.

Projects like this can take a while to set up, says Lynam – it can take time to get everyone on board – but once they get going, most of them keep going.

Part of what the Travel Foundation does before they finish the project is to change hotels’ sourcing process, so that if someone who’s excited about sourcing locally leaves, the farmers don’t risk being left high and dry when new hotel staff come in.

They also change the payment processes to ensure suppliers are paid quickly for their produce.

And he believes it could be done on a wider scale: “There’s no good reason why proactive, local sourcing shouldn’t be business as usual across the hotel industry globally.”

In Crete, nine hotels are working with 190 local farmers – as well as a local monastery – to produce wine, oil and bread. The hotels have tastings and cooking sessions for guests, as well as using it in their kitchens.

The project is run by Futouris, another sustainable travel initiative, in conjunction with the Tui Care Foundation, and was recognized as one of the best practice examples in sustainable tourism by the European Commission.

Sustainable outside activities

When we think of an all-inclusive vacation, we think of tourists rarely straying further than the pool or the bar, or taking coach tours on escorted trips. But is that really so bad?

“There’s a lot to be said for guiding groups around places, managing their behavior, and where they go and when – it can help with overcrowding and in sensitive places,” says the Travel Foundation’s Ben Lynam.

“In a historically significant place, it might be an idea to recommend that people can only visit in groups. It’s a more managed process, and you can know how many people are going, how that should happen and manage the conditions around it.”

Properties could also revise the kind of excursions they offer, adds Justin Francis – adding in trips to local projects and places that support cultural heritage (yes, that means that museum you might normally skip for a cocktail by the pool). There’s no reason why tour reps – who are based at hotels, on hand to deal with customers’ needs – shouldn’t be local either. Currently, they tend to be expats.

Constructing sustainability from the start

The resort of Belek, 25 miles east of Antalya on the Turkish Riviera, has prioritized environmental issues from the day it was founded in 1989. No fewer than 52 biological diversity programs are currently in progress, including sea turtle protection projects and one to conserve the pear of Serik, an endemic plant that’s found nowhere else in the world. The Belek area is home to over 120 species of birds – a quarter of Turkey’s entire bird population.

Belek’s Calista Hotel was the first in the country to win a “green star” – awarded by the government to hotels with ecologically-friendly initiatives – and has energy management certificates, too. It sits on a blue flag beach and protects the loggerhead turtles which nest there.

Nests are also provided for birds, squirrels and local cats, there’s recycling in public areas, and guests are encouraged to use public transport. Rooms have aerators to reduce water usage, and the pools use minimal chlorine (chlorine-free pools are not allowed in Turkey). Excess food will be sent to a food bank – just as soon as another property signs up to the scheme.

“Actually, the most efficient way to manage water, energy and waste is probably in large resorts,” says Justin Francis. “Denser living creates efficiencies because the rooms are closer together.”

But he says we could also go further.

“There’s no reason hotels couldn’t reflect local architecture and be made from sustainable materials, and there’s no reason fixtures and fittings couldn’t be made sustainably,” he says. “The art and décor is currently made to look local, but there’s no reason why it couldn’t be local.”

The Marriott Port-au-Prince, for example, has local art on the walls. Its soaps and amenities are made locally using herbs, nuts and fruits from Ayiti Natives, coffee is from Haitian growers, and 90% of the kitchen produce comes from a local cooperative.

It’s also the only hotel in Haiti to recycle plastic bottles. Next month it’ll start recycling paper coffee cups and straws, too. The hotel, which was newly built for its 2015 opening, also has thorough insulation, gets part of its energy from a solar farm, and warms 60% of its hot water through solar panels.

Nontoxic waterworks

Sewage is probably the last thing you want to think about on vacation, but if you’re wondering why the coral around your hotel is dying, or there’s little marine life in the water, it might not just be to do with the climate crisis.

Dr Craig Downs from Haereticus Environmental Laboratory calls himself a “forensic investigator” of the depths. He can analyze seawater and tell not just what’s polluting it, but where it comes from. And he says that inadequate sewage and wastewater treatment is decimating the seas.

Everything from the sunblock and body cream you slather on to chemicals from the medication you take and excrete ends up in the surrounding land and sea, he says, if hotels aren’t processing it correctly.

Effective wastewater systems cost money, however. The same goes for non-polluting golf courses – the fertilizers and fungicides used on the grass can leech into the ground, but lining them can prevent the worst from happening.

Downs says that installing membrane bioreactors – which combine microfiltration with a biological process – can reduce the pollutants by up to 90%. But a state of the art model would cost in the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

A smaller, modular membrane bioreactor – which would take up an acre of land, complete with a settling pond and plant odor scrubbers – can cost around $10,000, he says. That’s a significant investment for a small hotel – but less so, potentially, for a big chain planning an all-inclusive.

Hotels wanting to go greener should also avoid white linen, so they don’t have to use bleach, which can harm bioreactors, says Downs.

So if an all-inclusive hotel invested in a decent sewage system and switched the clinical whites for colored sheets and towels, they’d have a significant – and positive – effect on the environment.

Why we need it

“People make assumptions about mass tourism, and they really shouldn’t,” says the Travel Foundation’s Ben Lynam. “There’s unsustainable niche and solo traveling, and there are sustainable and unsustainable hotel models.

” ‘Mass tourism’ as a concept sounds bad, but I’d argue we’re at mass tourism levels with most forms of travel anyway. It’s more about the way you manage those impacts.”

Justin Francis agrees. “Big all-inclusive resorts aren’t bad by definition. Most aren’t sustainable, but theoretically they have the potential to be.

“And the only way we get real change through is not with tiny businesses, but with all forms of travel – including mass tourism.

“Maybe that’s a modern solution to the problems we face. Done the right way, there’s a real need for it. Otherwise, overtourism will become an impossible problem.”