Growing up in South Africa in the 1950s and ’60s, it was inevitable that Penny Siopis’ work would be political.

The multimedia artist was born during apartheid, South Africa’s period of legislated segregation, and began her career in the 1980s when anti-apartheid activist (and later president) Nelson Mandela was imprisoned. The “momentous changes of the country” fundamentally shaped her art, said Siopis.

“You’re not just painting or making work about the empirical changes that you witness, but actually the psychological changes,” she said.

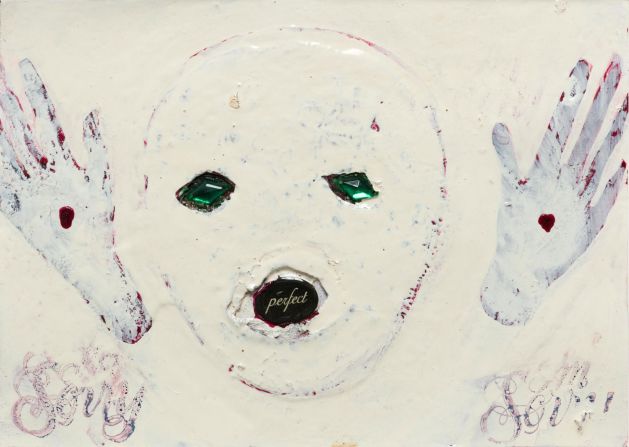

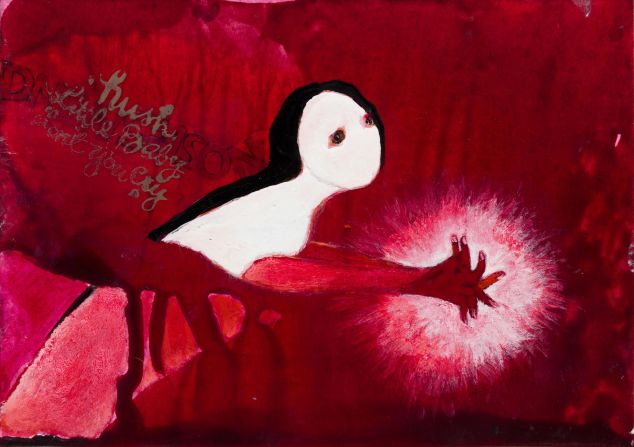

Siopis expressed some of those psychological changes in her series “Shame.” Comprising 165 paintings created over three years between 2002 and 2005, Siopis said the series was a response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission – a government body established to investigate human rights violations that took place during apartheid – that explored the “questions around culpability, vulnerability and shame that the Commission raised.”

Now, nearly two decades after starting on the series, Siopis revisited “Shame” earlier this year in a digital art work, examining gender-based violence in South Africa.

The psychology of shame

Dynamic, abstract figures dominate the paintings in shades of orange and red, contrasted against the sharp white background. Siopis used lacquer and oil paint to create a “distressed” and “agitated” look, along with phrases from rubber stamps she found in a children’s craft store.

Shame is a universal emotion that plays out both privately and publicly, said Siopis. It’s that dichotomy that she delves into in each tile-sized painting. Examining the “complicity” of the individual in apartheid South Africa, Siopis tries to give form to the mental and emotional turmoil of the period – and the scars it left behind.

“I think people in the larger world are very interested in South Africa being a kind of microcosm of social-political experiences across the globe, but they often don’t have the sense of what it is: the psychological complexity of what it might mean to have lived in a society like ours, and still live in a society like ours,” said Siopis.

Shame revisited

Revisiting the topic earlier this year, Siopis zeroed in on the “psychosexual” element of shame. “Shadow Shame Again” is a six-minute digital film created during the coronavirus pandemic, as South Africa reckons with what its president Cyril Ramaphosa calls “another pandemic”: violence against women. Gender-based violence has been on the rise in South Africa in the past year, with the country already having one of the highest rates of rape in the world.

Using “found footage” – fragments of 8mm and 16mm film Siopis bought at flea markets – the film was commissioned by the Peltz Gallery in the School of Arts at Birkbeck, University of London.

Splicing together home video footage of women and girls against words and music, the video is dedicated to Tshegofatso Pule, a 28-year-old pregnant woman whose murder in June 2020 started national protests. “The mental image became a rallying cry in protest, and a locus of national shame,” Siopis writes in the film.

While shame is a “toxic” feeling, Siopis believes it is also the foundation of empathy. “(People) find in these artworks a space to imagine what it might have been like, and what it might be like in South Africa, rather than just to take the given media narrative,” she said.

Taking the viewer “beyond the empirical or statistical,” Siopis hopes her art can spark conversations and create a new story for South Africa.

“We’re often afraid of change,” she said. “It always amazed me when people said under apartheid, ‘Oh, we can’t change overnight.’ Well, what the pandemic has said is yes, you change overnight: you can, we all do, it’s possible. And this is the global change. I embrace change, and I think my medium, the way I work with the medium, somehow gives a physical form to that embrace.”