Thousands of historical images from across Ireland are being brought to life in color for the first time, thanks to a new AI-led photo project.

Combining digital technology with painstaking historical research, professors John Breslin and Sarah-Anne Buckley at the National University of Ireland, Galway, have been able to turn photos, originally shot in black in white, into rich color images.

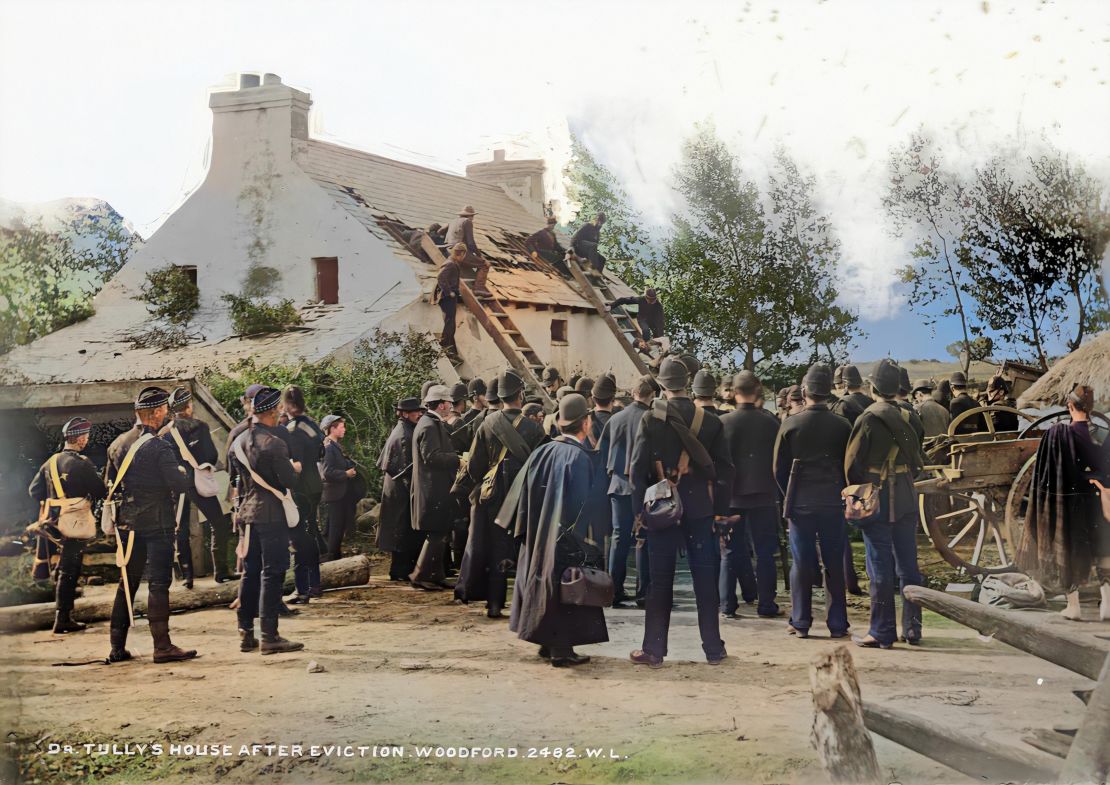

The collection spans centuries and regions of Ireland, as well as the country’s diaspora. It includes portraits of key figures like Oscar Wilde and poet W.B. Yeats, as well as defining moments in history, like the Titanic setting sail from the Belfast shipyard where it was constructed.

Yet, some of the most compelling photos depict everyday scenes – people herding pigs, spinning wool or packed onto the back of horse-drawn carts. And while poverty is evident in pictures of barefoot villagers crowding around for a photo, or of Dublin’s working-class tenement buildings, there are also well-to-do family shots and depictions of upper-class pastimes like fox hunting.

“There were many different social classes in Ireland, as in many countries, so I think it’s important to show the full range,” said Breslin in a phone interview from Galway, on the west coast of Ireland. “We have a mixture of the wealthier classes and the gentry, and then you’ve got people who are just trying to survive and gather water and turf (peat) to burn on their fires.”

The project, “Old Ireland in Colour,” now has dedicated social media accounts with tens of thousands of followers. A new book of the same title is also bringing together more than 170 of the images, painting a compelling picture of life on the island from the 1840s through to the 1960s.

Deep learning

The project began when Breslin started experimenting with old photographs of his grandparents for a personal genealogy project. After discovering an AI-powered colorization tool, DeOldify, he started applying the technique to photos from archives and libraries across Ireland.

Using a process known as deep learning, AI software can be taught how to colorize. The “training” involves analyzing thousands of normal color photos, as well as black and white versions of the same images, to help it understand which colors correlate to different shapes and textures, explained Breslin, who specializes in engineering and computer science.

Then, when the software encounters an image that only exists in black and white, it knows “what the colors should probably be,” he said. “So, for example, the grass or trees or the sea – it knows from those textures and shapes that they should be green or blue.”

AI has its limitations, however. There were certain idiosyncrasies to life in Ireland that the US-developed software was not trained to recognize.

“An average kind of color (of a roof), around the world, might be a terracotta, an orange or a kind of a brownish-type tile,” Breslin said. “Whereas in Ireland, the roofs were typically slate, which is gray or black.”

This is where his collaborator, Buckley, who specializes in Irish social history, came in. The pair researched everything from clothing and pigments available in Ireland at the time, to the uniforms worn by various military units, before manually changing colors and shades based on what they found.

For a photo of revolutionary politician Constance Markievicz, they even consulted passenger records from New York’s Ellis Island – where she was processed among the millions of Irish immigrants arriving in America between the 1890s and 1950s – to determine that her true eye color was blue.

Colorization debate

Despite the painstaking approach taken by the two researchers, photo colorization remains controversial among academics. Some historians believe software like DeOldify can produce misleading results that obfuscate, rather than enhance, the content of old photographs.

But the practice is “nothing new,” Breslin said, adding that people have been colorizing photos “since the advent of photography,” albeit without the help of AI or other software like Photoshop. He also argued that his images exist in addition to, not instead of, the originals.

“We’re not vandalizing the negatives,” he said. “You can always go back and find the original photograph, and throughout the book we provide pointers to the original collection.”

In making old images more accessible, Breslin hopes his and Buckley’s project can help engage people who may not otherwise be interested in history. If the success of their book so far is anything to go by (though not released in North America until next month, it was among Ireland’s best-selling titles in 2020), he may well be right.

“We’re being bombarded with so much information, knowledge, bite-sized media and content, so, for the younger generation particularly, it can be hard for history to compete,” Breslin said. “It’s important to be able to relate more to our history, and colorization definitely makes things more relatable.”

“Old Ireland in Colour,” published by Merrion Press, is available in North America from April 5, 2021.