Famous and aspiring artists alike have made their mark on New York City in the form of public murals, from Banksy’s “Hammer Boy” on the Upper West Side to Keith Haring’s enduring “Crack is Wack” sign, which has stood in East Harlem since the late ’80s.

Some murals have been lost to history, such as the massive, unfinished Diego Rivera painting commissioned for the Rockefeller Center in 1932. Rivera’s patron, Nelson Rockefeller, fired the artist after he refused to remove a portrait of Vladimir Lenin, and Rivera’s work was later replaced by Josep María Sert’s idealistic “American Progress,” which still stands today.

Murals are an opportunity for bold, highly visible statements. Following the waves of worldwide protests responding to the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, new public artworks have sprung up across the US and other parts of the world to send messages of hope, anti-racism and solidarity, including the bright yellow lettering of “Black Lives Matter” in front of Trump Tower in Manhattan.

The recently re-published book “Murals of New York City” features historically significant murals at sites ranging from the Harlem Hospital to the Metropolitan Opera. The pages feature the work of celebrated artists, including the six listed below, and capture the rich cultural history of the city.

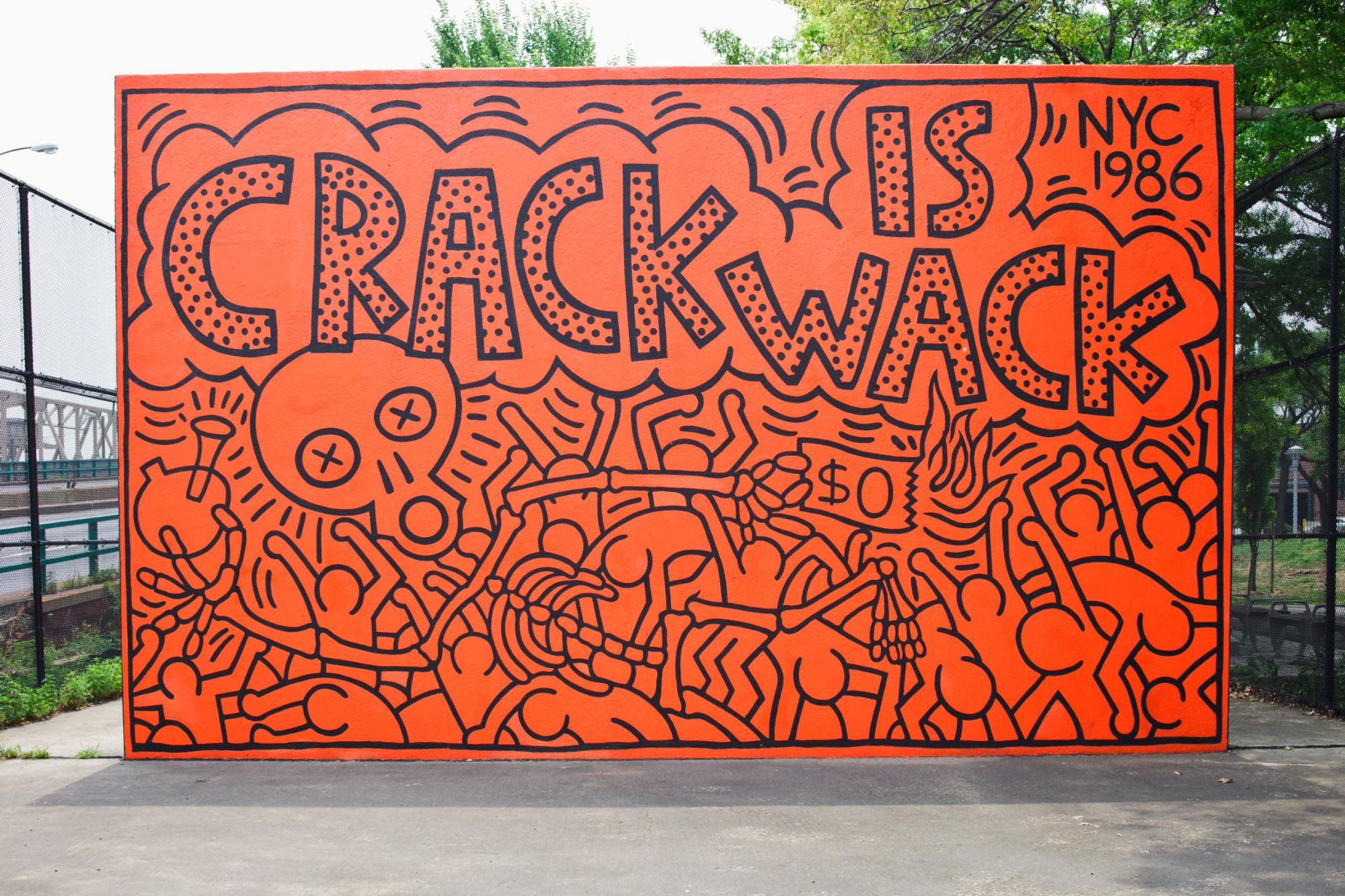

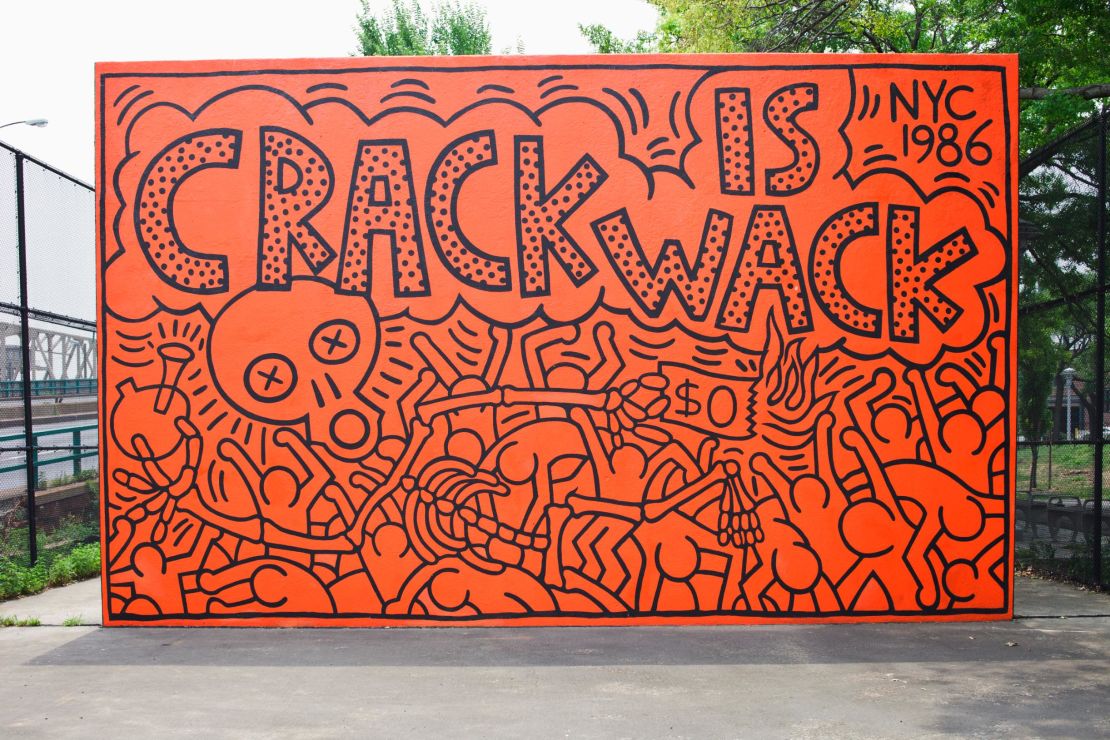

“Crack is Wack” by Keith Haring, East Harlem (1986)

Known for his playful, cartoon-like figures and dynamic silhouettes, Keith Haring’s street art commented on social issues including apartheid, LGBTQ life and the AIDS epidemic. During a brief but explosive career, before his death at 31 from AIDS-related complications, Haring left his mark on the city with a series of murals that still stand today.

One of his most famous is the bright orange “Crack is Wack” sign, from 1986, that greets passersby on Harlem River Drive. When he first painted it as a response to the city’s drug crisis, Haring was arrested and fined $25.

But the mural you can still see is not, in fact, the original. After another artist changed the wall art’s wording to “Crack is It,” New York City maintenance workers painted over the entire design. When the city’s parks commissioner Henry Stern contacted Haring to apologize, he offered him the chance to paint more murals around the city.

Haring repainted “Crack is Wack” in the same place, along with a number of other large-scale artworks across the city. In 1986, he donated a mural to the Woodhull Medical Center in Brooklyn in acknowledgment of its research into HIV/AIDS. Three years later, he created an erotic composition to celebrate LGBTQ New Yorkers, in Greenwich Village, to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

Various Artists, Harlem Hospital Center (1936)

As the Great Depression leveled US industries, including the arts, the Works Progress Administration’s (WPA) Federal Art Project commissioned over 500 murals to be painted for New York’s public hospitals during the 1930s.

With African Americans routinely being denied work, influential Harlem Renaissance artist Charles Alston and Harlem Artist Guild president Aaron Douglas urged the WPA to help Black artists gain employment and recognition.

In 1936, three Black artists – Alston, Vertis Hayes and Georgette Seabrooke – as well as Sicilian immigrant Alfred D. Crimi, were commissioned to create a collection of murals for Harlem Hospital. The sketches proposed by Alston, Hayer and Seabrooke were, at first, rejected by the hospital supervisors for their depictions of African American history and contributions to society. After the Harlem Artists Guild sent letters of complaint to the mayor and President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the artists’ murals were painted as originally planned.

Hayes’ eight-panel mural “Pursuit of Happiness” chronologically follows the history of African Americans, transporting viewers from Africa to America, then from the the agrarian South to the industrialized North. Alston painted two murals, titled “Magic in Medicine” and “Modern Medicine,” which together form a dialogue between African folk medicine and Western medicinal practices.

Seabrooke, the youngest artist and the only woman of the group, painted a near 20-foot-long mural titled “Recreation in Harlem.” The artwork was meant to show Black residents enjoying daily life in upper Manhattan, but, at the insistence of hospital officials, she added White figures as well.

Following Harlem Hospital’s relocation in the 2000s, the artworks were moved and restored, finding a new home at the Harlem Hospital Center’s Mural Pavilion.

“The Triumphs of Music” by Marc Chagall, The Metropolitan Opera (1966)

In 1966, modernist artist Marc Chagall painted two colorful, large-scale murals for the newly opened Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center Plaza. Chagall was born to a Hasidic Jewish family and grew up in Montparnasse, France, during the golden age of Modernism. When Nazi Germany invaded France during World War II, he and his family were smuggled into New York in 1941 with forged papers.

Chagall gifted the Metropolitan Opera “The Sources of Music” and the “Triumphs of Music.” Both feature a swirling mix of mythical creatures, bright colors and depictions of musical instruments. The vivid yellow “Sources of Music” shows King David playing a harp, while the red “Triumphs of Music” illustrates an angel blowing a trumpet, with ballerinas, an orchestra and animals in the background. The monumental murals hang on the north and south sides of the lobby, covering two stories of the building.

“Table of Universal Brotherhood” by José Clemente Orozco, The New School (1931)

Painted by Mexican artist José Clemente Orozco, the five murals at The New School in Greenwich Village comment on revolution, world leaders and the contributions of artists, scientists and laborers to society.

Though Orozco was unable to fight in the Mexican Revolution himself, due to health issues, his works nonetheless contributed greatly to Mexico’s post-revolution muralist movement, alongside those of his contemporaries Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros.

Orozco’s murals bring together revolutionaries including Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin, Yucatán governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto and Indian poet and activist Sarojini Naidu. His mural “Table of Universal Brotherhood” depicted 11 men of different nationalities and ethnicities – including men of Sikh, Tartar and African American heritage – sitting together in unity. His composition “Struggle in the Orient” shows African and Asian slaves protesting their bondage alongside representations of the overlapping Mexican and Russian Revolutions.

Over 20,000 people came to view the murals in the weeks following their inauguration in 1931. At the height of the “Red Scare,” however, Orozco’s murals sparked controversy for their inclusion of Lenin and Joseph Stalin. The New School administration covered the portions of the artwork featuring the Soviet leaders with a yellow curtain until students and faculty members compelled them to restore the work.

The Waverly Inn and Garden mural by Edward Sorel (2009)

Since The Waverly Inn opened as “Ye Waverly Inn,” a year after Prohibition became law in 1919, the New York watering hole has become a Greenwich Village landmark. In 2006, former Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter bought and refurbished the establishment. Three years later, he tapped famed illustrator Edward Sorel, known for his caricatures in the New Yorker and other magazines, to paint a mural in the inn’s dining room.

Sorel’s mural features nearly 50 of the Village’s most famous regulars from the last 150 years, including Marlon Brando, Jackson Pollock, Fran Leibowitz and Bob Dylan. Instead of painting directly onto the wall, Sorel created a separate watercolor, which was then digitally enlarged, printed and installed like wallpaper onto the Waverly Inn’s interior. As a result, when part of the work was destroyed in a fire in 2012, it was easily replaced.

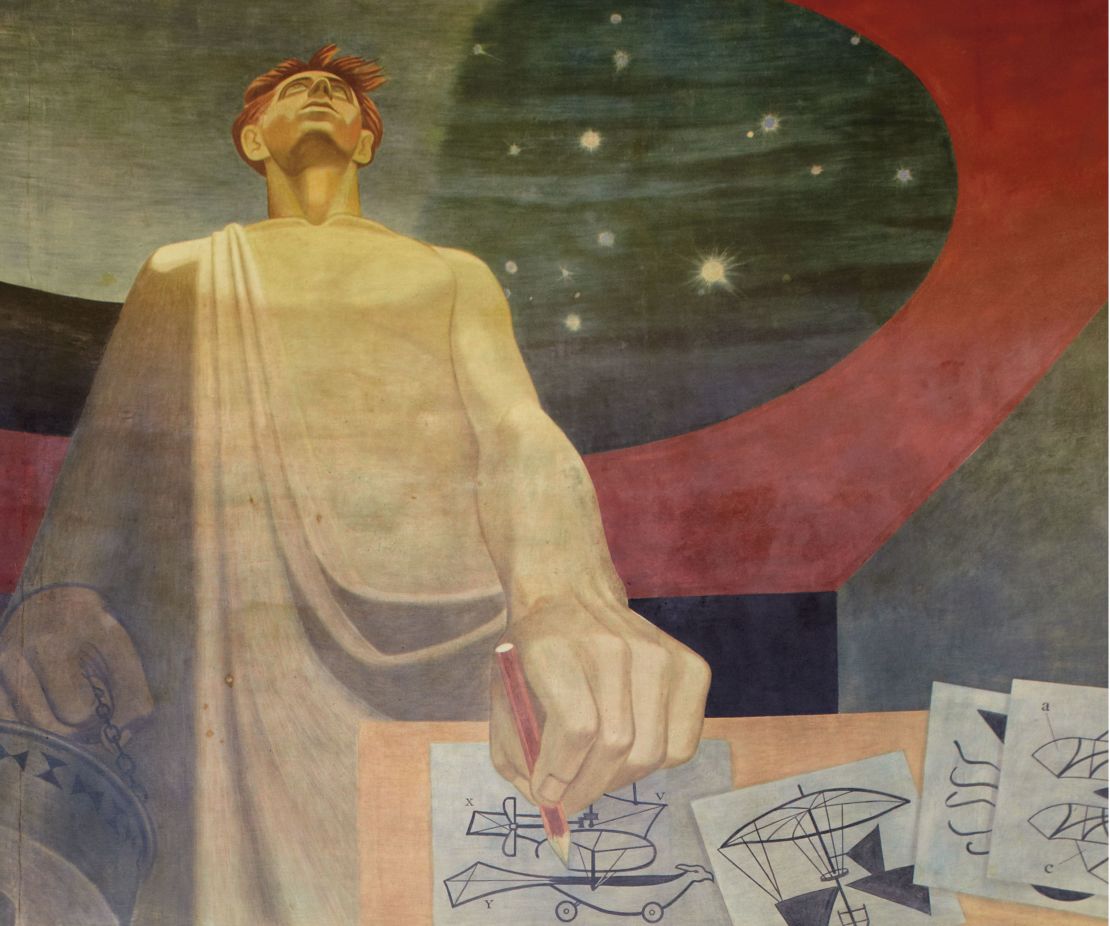

“Flight” by James Brooks, Marine Air Terminal (1940-42)

Terminal A of LaGuardia Airport is where you’ll find artist James Brooks’ Depression-era public artwork, “Flight.” The 235-foot, circular mural, painted between 1940 and 1942, was the largest and the last mural produced with WPA support.

With “Flight,” Brooks illustrates the evolution of aircraft technology and humankind’s quest to conquer the skies, shown through depictions of Greek mythological characters Icarus and Daedalus, artist Leonardo da Vinci and Pan Am seaplanes.

During the peak of McCarthyist anti-communism, however, the city’s Port Authority deemed the mural too socialist. The artwork was painted over in gray in 1952. But because Brooks added a varnish to his mural, the new paint did not permeate the work.

By the late 1970s, aviation historian Geoffrey Arend rediscovered the artwork and began campaigning for its restoration. In 1980, businessman Laurance Rockefeller and Reader’s Digest founder DeWitt Wallace put up $75,000 to have the mural restored (Brooks was then in his 80s). His mural has since become a New York City landmark.

“Murals of New York City,” published by Rizzoli, is available now.