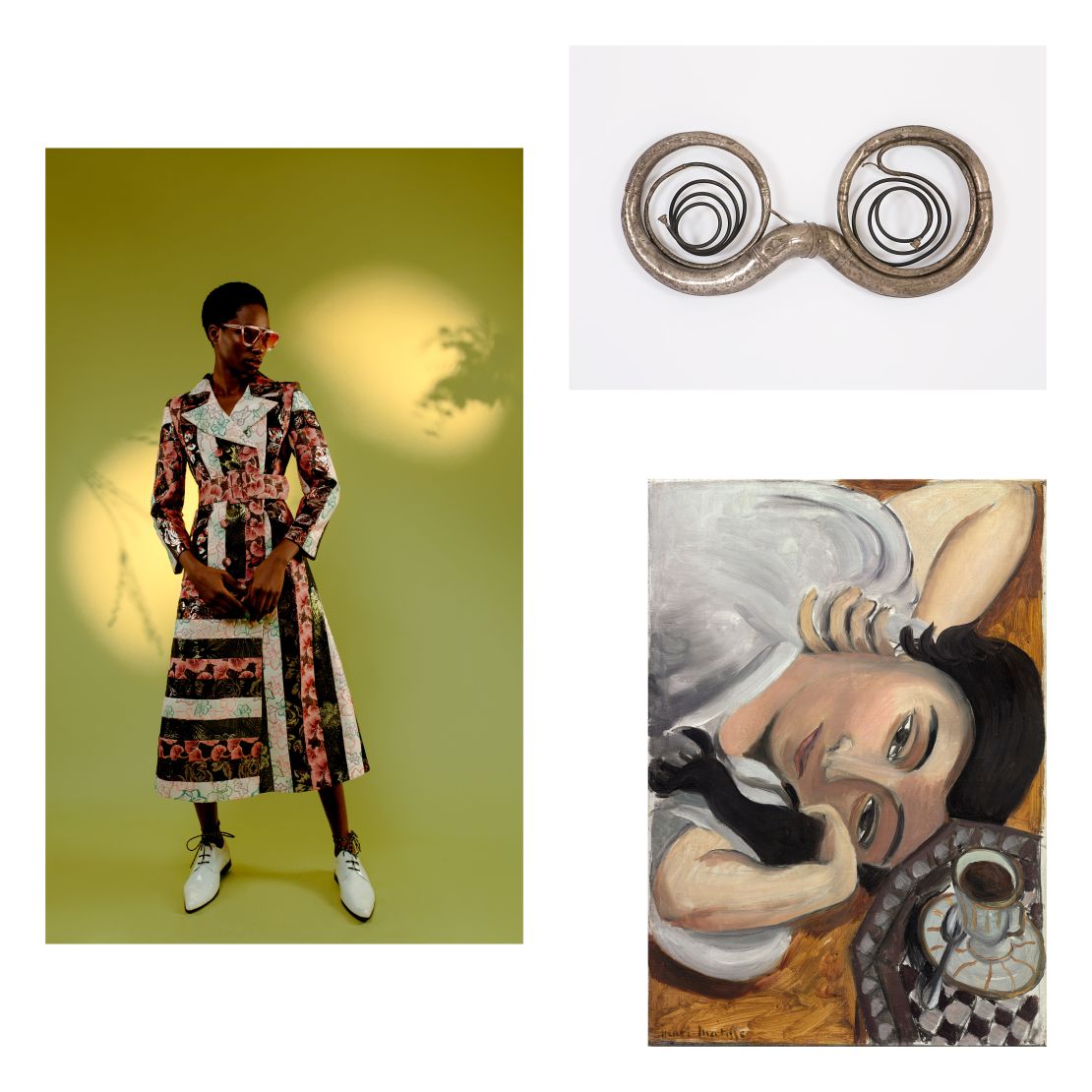

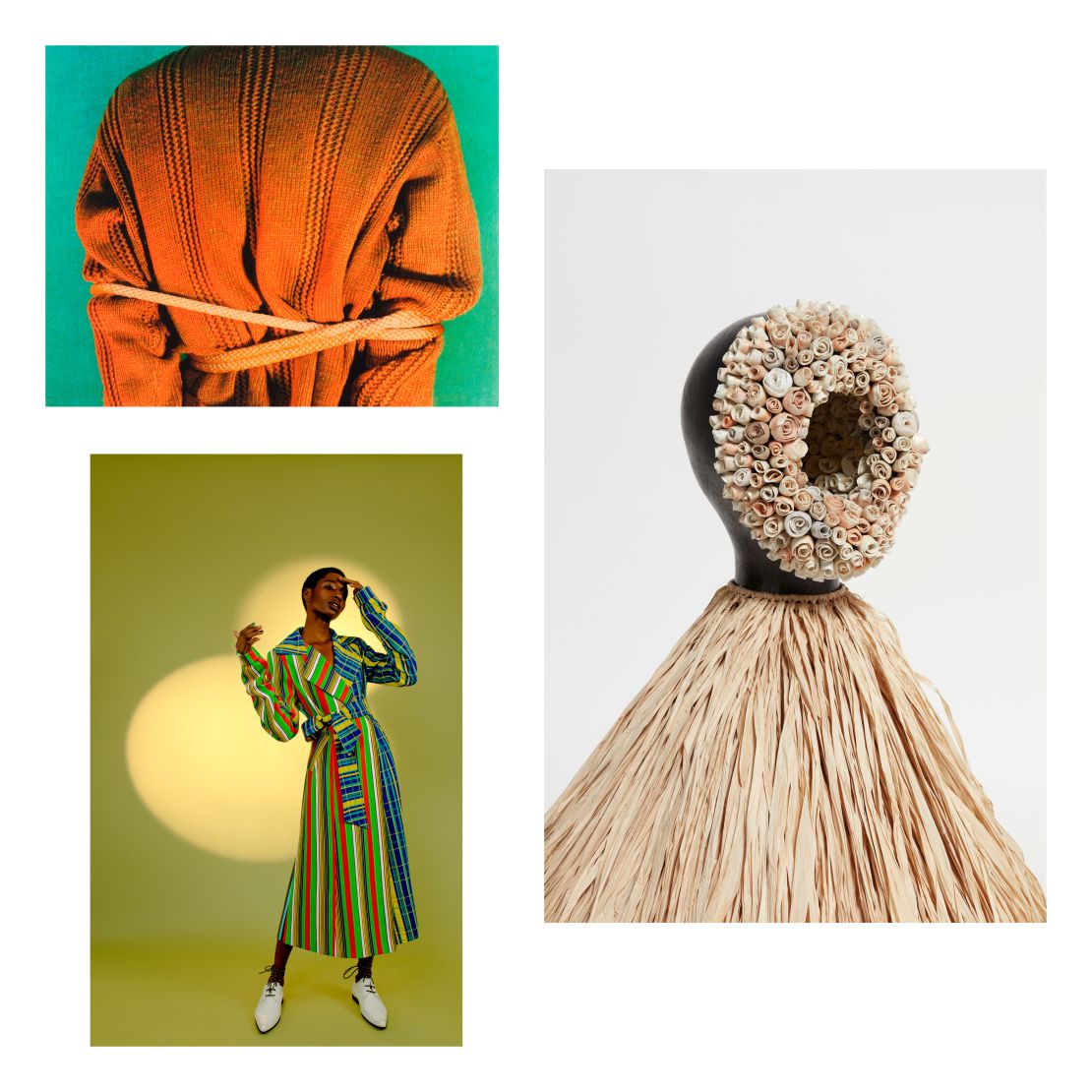

Editor’s Note: Valerie Steele is director and chief curator of The Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology. The following is an edited excerpt from the book “Duro Olowu: Seeing,” which was created to accompany designer Duro Olowu’s curatorial project with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. For the exhibition, Olowu combined his own work with objects from public and private art collections across Chicago that illustrate his point of view.

Ever since Nigerian-born British fashion designer Duro Olowu launched his eponymous label in 2004, his aesthetic has remained remarkably consistent. Known for his use of color and pattern, Olowu also favors the sharply tailored silhouettes of his multicultural 1970s upbringing, including fitted jackets, precision-cut wide-leg trousers, billowing capes and kimonos, and intricately cut yet liberating dresses with hemlines below the knee – all rendered in vivid and unusually juxtaposed fabrics, patterns, and textures.

His first collection included one dress with an empire-waist silhouette that combined vintage couture silks and contemporary fabrics of his own design. After editor Sally Singer featured the dress in American Vogue, it received international acclaim and sold out at Barneys New York, Ikram in Chicago, Browns and Harrods in London, and other international stockists from Milan to Japan. Dubbed the “Duro Dress,” it became Olowu’s signature look, and in 2005 he won New Designer of the Year at the British Fashion Awards – the only designer ever to have won this award before their first runway show.

From the outset, the designer’s self-taught vision – Olowu trained as a lawyer – was bold, fresh, and elegant, a reflection of a refined aesthetic eye and firm philosophical grounding: “I really want people to understand what fashion and the culture of style could mean if one thought beyond the usual boundaries but also always about the wearer.”

This responsiveness to the individuality of bodies and the aspirations of those who wear his clothes is informed by lessons learned at a young age about the power of fashion. Regardless of where he was in the world, he was exposed to people who dressed intentionally, presenting themselves in ways that spoke volumes about their identity.

This includes his Jamaican mother – who mixed clothes from Yves Saint Laurent’s Rive Gauche line “with pieces made from fabrics she picked up in Nigeria, Switzerland, and London that she would have run up by tailors in Lagos” – but also the other women who surrounded him as a child in Lagos, Nigeria, as well as his cousins and aunts in London.

Using both his singular aesthetic and business acumen to carve out a niche in the industry, Olowu has attracted an impressive clientele of powerful and loyal women. And underlying his creation of fashion for women is a form of radical respect: “I’m just amazed by how women can do so much regardless of natural or imposed obstacles, and I feel that it’s my duty to make sure they look good and feel comfortable doing it… Whether I’m initially inspired by Eileen Gray, Miriam Makeba, Pauline Black, or Amrita Sher-Gil, I always end up designing for women of all ages and ethnicities, women whose way of life and work I respect. Then I hope that the clothes I’ve come to, with them as inspiration, would be of interest to them.”

“Duro Olowu: Seeing,” published by Prestel and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, is out now.