Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from the prologue of John Blake’s new book, “More Than I Imagined: What a Black Man Discovered About the White Mother He Never Knew.” It contains language that some readers may find offensive.

I was about five years old when I was abducted. It was one of the most beautiful days of my childhood.

A couple of strangers lured me away from my front porch that summer afternoon. I knew they were intruders, but they somehow felt familiar. I wasn’t afraid.

They were white — a young woman and an older man. I hardly ever saw white people in my Baltimore neighborhood, where most residents viewed them with suspicion, if not outright hostility. Yet they slipped past my family, took me by the hand, and led me to a baseball diamond across the street. They steered me toward the middle of a lush, sprawling field, where the woman gave me a white paper kite.

What happened next is just a fragment in my memory: squinting at the summer sky as I chased the kite, seeing the sunlight reflect off the blond hairs of the woman’s pale forearms, watching as a gust of wind caught the kite and wondering if I, too, would be lifted into the air. As I peeked over my shoulder, I caught my abductors standing back to appraise me, nodding and smiling with approval. I felt wrapped in a cocoon of love.

And then it was over. I somehow ended up back at home without the strangers ever bidding me goodbye.

I never mentioned that afternoon to anyone, because I thought I would get into trouble. And a part of me hoped that someday my mysterious visitors would return.

I kept that memory tucked in my back pocket until one day, forty years later, when I was going through an old family photo album. I decided to try to solve the mystery. I called several relatives about that strange encounter. “Who was that couple?” “Why didn’t anyone stop them from taking me?”

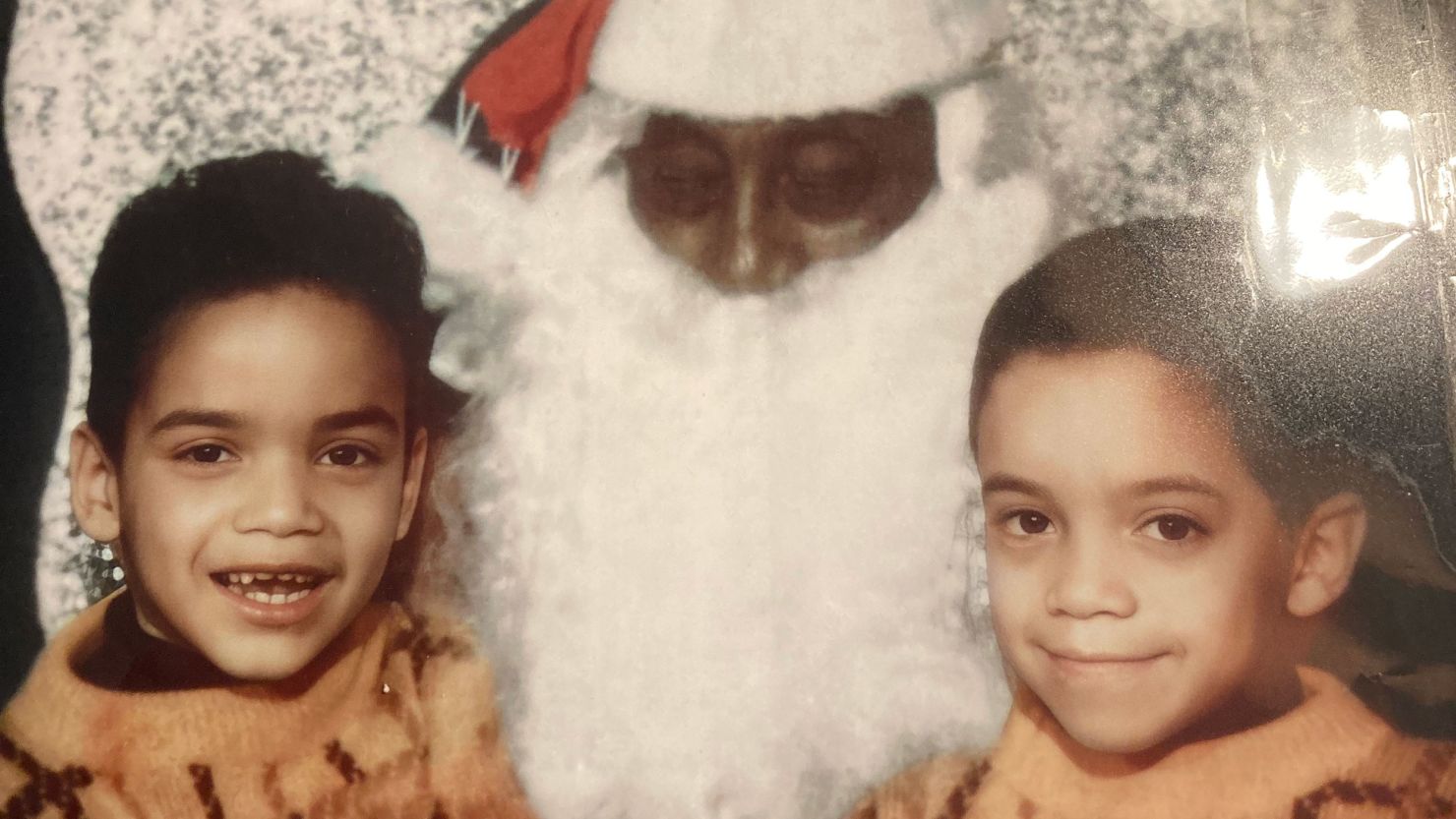

No one knew what I was talking about. Not even my younger brother, Pat, who was always at my side when we were children.

“It was a dream,” Pat said, “or wishful thinking.”

I was baffled. I had the kite. I had stored it in a corner of my bedroom and kept it as a memento for so long that the paper disintegrated. I had relied on the memory of that golden afternoon to help me get through the many tough days that made up my childhood.

Was Pat right? How could such a vivid memory be an invention? And how could I explain the kite that I kept as a souvenir?

My bittersweet return to West Baltimore

On Monday, May 4, 2015, I found myself wading through a crowd of angry protesters in Baltimore, still chasing that memory. As a journalist at CNN, I’d been assigned to cover violent racial protests that had erupted in my childhood community.

But another story also drew me home. It was a story about my family, about how I’d tried to move past the same kind of anger that had engulfed my neighborhood — to feel as free as I did when I was a child flying a kite on that postcard-pretty summer day.

I peeked at my cellphone. It was 4:36 p.m., and I was about to go live on national television. A sweaty, bearded CNN technician attached a microphone to the lapel of my navy-blue polo shirt. I cleared my throat as I glanced behind me at a crowd of protesters and curiosity seekers who had gathered to watch my interview. We were standing outside Baltimore’s city hall complex, in a tiny park where the national media had camped out.

For more than two weeks, violent protests had rocked the city after a young Black man named Freddie Gray died in police custody. West Baltimore was filled with burning stores, smashed police cars, and at least three thousand National Guardsmen and police in riot gear facing off against angry protesters.

I’d been asked to appear on air because I’d written a first-person account for CNN of what it was like to grow up in the neighborhood where Gray had lived and where the racial protests had erupted.

To prepare for my television appearance, I took a quick drive to my old neighborhood to assess the damage. It was the first time I’d set foot there in about fifteen years.

I was stunned. Half the homes on the block where I grew up were vacant, boarded-up husks, some with collapsed walls spilling onto sidewalks. The sprawling baseball field where I’d flown my kite was choked with weeds and fenced off with locked gates. The constant hum of street life that I remembered — neighbors gossiping on the porches of their row houses; young men and women flirting on the corners; “Arabbers,” or Black fruit vendors, calling out prices as they led their lavishly decorated horse-drawn carts down the street — was gone.

I expected looted stores and charred buildings. What I didn’t know was that my community had died long before the Freddie Gray protests.

Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. West Baltimore had one of the highest murder rates in the nation and had become a symbol of Black criminality and urban decay. It was the setting for the brutal HBO series, “The Wire.” It had also become a popular conservative talking point: Here’s what happens when Black mayors run Black cities with “failed liberal policies.”

When some white people learn where I’m from, their eyes widen with surprise before they ask two questions: “How real was ‘The Wire?’” and “How did you get out?”

The story I didn’t know how to tell

Poppy Harlow, the CNN anchor who was assigned to interview me, had questions of her own. Her head was bowed as she flipped through a stack of papers. She looked up and turned to me with a bright smile.

We went live. Harlow and I talked. As we approached the end of our interview, she asked me, “Just very quickly, John, I want to ask you personally, What was it like for you to come back here on assignment?”

I lowered my head and sighed. There were so many feelings to sort through.

“It was very bittersweet,” I said. “It’s always good to see home, but it’s not good to see home like this. I feel like there are kids here who are like I was, fifteen or sixteen, and I wonder, Can they make the journey I made? I have doubts about that, and that’s very sad.”

Harlow thanked me. Our interview ended. I unclipped the microphone and stepped away, shaking my head in disappointment. The interview went so fast. There was so much more I wanted to say.

But what would I have told Harlow, knowing what I know today? I would have told her that if you think growing up as a young Black man in my neighborhood was tough, try doing it as the son of a Black father and a white mother in a place where many despise white people.

And if you want to talk about Black anger, Harlow, I have a little experience with that topic. Try reconciling with your white family while they claim they were never racist — even though they thought that Black and white people should be kept separate and even though one referred to your father as “this nigger.”

Harlow invited me to appear on her show because my essay attempted to explain why so many Black men had disappeared from inner-city Baltimore. But I never told her or CNN’s audience that my white mother had vanished without explanation after my birth.

That’s the story I wanted to tell, but I didn’t know how.

My life doesn’t fit into a tidy narrative

I’ve covered the biggest stories about race in America for the past twenty-five years, and most of those stories follow a pattern: Angry Black or brown people indict white people for their racism after something terrible happens. Chastened white people experience a “racial reckoning.” The wave of moral outrage passes, the news cycle moves on, and Black and brown people continue to seethe. I get those stories. I’ve felt that anger.

I saw racism as an either/or proposition. Either you’re a racist or you’re not. There was no in-between. But my experience with the white members of my family didn’t follow that script. My white relatives ended up showing me that I wasn’t immune to racial prejudice and that they could teach me something about empathy and forgiveness. I never saw that story coming.

I didn’t know how to tell Harlow any of that because my story doesn’t fit traditional narratives about race or identity. There are elements that are too contradictory, embarrassing, and strange to share. Journalists are expected to be sober-minded operators who care only about the facts.

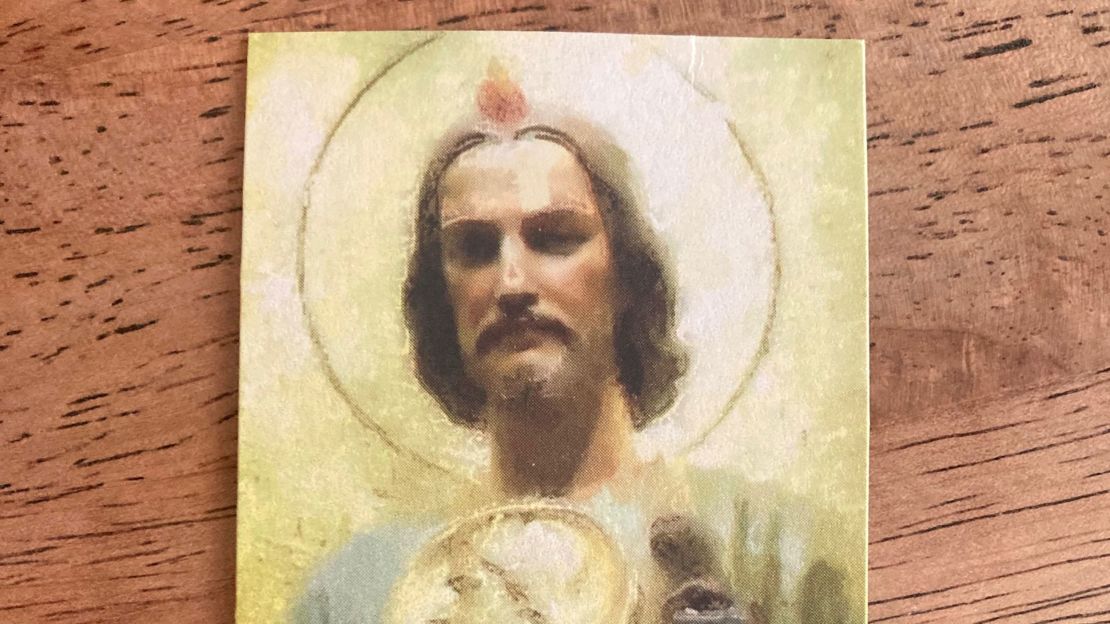

How odd would I have sounded, telling millions of TV viewers about a series of inexplicable encounters that forced me to ask a minister one day, “Can a person seek forgiveness from beyond the grave?” How could I have explained in a sound bite that a scar over my heart, which I thought was a birthmark, turned out to be a clue to my mother’s disappearance?

And how could I have described why a chance street-corner encounter with two strangers — a young Black man and a white man — did more to help me overcome my anger toward my mother’s family than all the books on racial reconciliation I’d ever read?

I wouldn’t believe half of it if someone told me the same story. Sometimes I still have trouble believing what happened — and I was there.

My personal journey was driven by a question: Where do I belong?

My return home forced me to ask questions I’d avoided for years. Now I know why my childhood abduction meant so much to me — real or not. I’ve yearned most of my life to feel what I felt that day: whole, not divided, free of anger at white people for what they did to me.

I know what that type of anger does to people. I see it virtually every day in the newsroom. We’re in the middle of a political and cultural civil war. Friends and family no longer talk because of politics. According to one political leader, our democracy is “in danger of imploding” because we’ve given up on the pursuit of a more perfect union. How can we find a way forward when we live in such separate worlds?

My family was split by the same racial hatred that divides America today. We found a way to move forward and heal. If we can heal, so can others.

I’m encouraged by something the Israeli historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari said: “The only thing that can replace one story is another story.”

Mine is another story.

I used to think that if more white Americans had more information — if you showed them enough videos of unarmed Black people being harassed or killed, if you cited enough history and facts about racism — they would change. But facts don’t change people; relationships do.

My white family members didn’t change because I shamed them with an impressive lecture on systemic racism. And facts didn’t change me. There was no diversity training I could call on to help me confront my feelings of betrayal and rejection — or the white relative who terrorized me.

I couldn’t lift that kind of weight with intellectual muscle. I needed spiritual tools. I first had to join a community where racial reconciliation was demanded and build relationships with people I regarded as enemies. I had to experience what one scholar called “radical integration.”

That kind of personal journey might sound complicated. But it was driven by two simple questions I had as a boy: “Where is my mother?” and “Where do I belong?”

That story begins with a tipsy Black man wearing a panama hat, driving his beat-up Ford truck home one night…

Excerpted from MORE THAN I IMAGINED © 2023 by John Blake. Published by Convergent, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.