Just when Beth and Kyle Long received the worst news of their life, an Ohio law made their searing pain even worse.

For four years, the Longs tried to have a baby, enduring multiple rounds of grueling fertility treatments. In September 2022, Beth finally became pregnant.

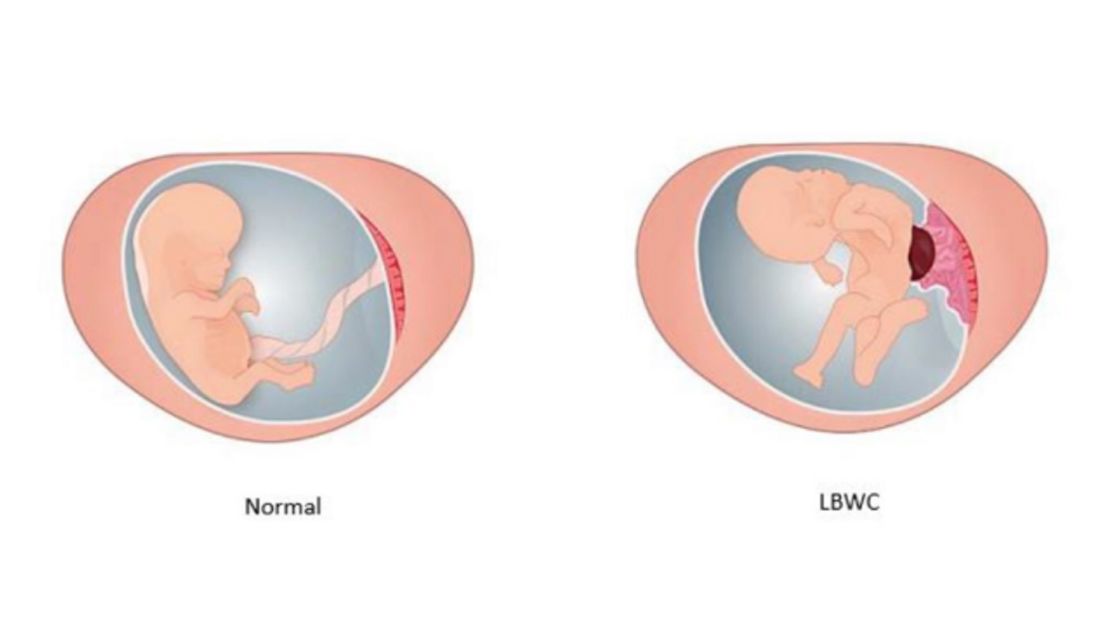

But an ultrasound four months later showed that most of the baby’s organs were outside the body.

The condition, called limb body wall complex, is rare.

“It’s just not survivable,” a doctor involved in Beth’s care told CNN.

“They will die. There’s no way there will be a life,” said Dr. Alireza Shamshirsaz, a spokesperson for the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, who was not involved in Beth’s care.

The condition posed dangers for Beth too, and the bigger the baby was, the higher the risk of complications, including dangerous bleeding that might require a hysterectomy. They say their doctor urged them to terminate the pregnancy as soon as possible.

But when the Longs tried to schedule the abortion, they found out that their insurance wouldn’t pay for it.

Beth takes care of breast cancer patients at a state-owned hospital. She’s employed by the state of Ohio, and state law bans her health insurance from paying for abortions except in certain cases.

Endangerment to the life of the mother is one of them, and although she was at an increased risk for potentially deadly complications, Beth’s life was not in imminent danger, and the Longs say their doctor told them the insurance wouldn’t cover the procedure.

Beth and Kyle would have to foot the bill: between $20,000 and $30,000. After spending $45,000 on fertility treatments, they didn’t have the money.

It took them three weeks to make arrangements to go to a hospital that could perform the complicated abortion at a lower price. It was hours away, in another state.

During that three-week wait – a wait they had to endure only because of the Ohio law – the risk to Beth of potentially deadly complications grew. Their ability to try to have another baby was delayed, and their “agony” couldn’t end, Beth said.

“I was in mental anguish,” Beth said.

“It felt very inhumane for both our baby and for my wife,” Kyle added.

The hospital they found was a three-hour drive away, in Pittsburgh. Away from their regular obstetrician, whom Beth had known for years; away from their doula; away from their friends and family. The Longs were alone.

‘The Long and Boring wedding’

Beth Boring and Kyle Long met on a dating app in 2015. Their first date was a storytelling event at a local arts organization.

Beth, who was 26 at the time, had been a teacher for special-needs children and was about to start nursing school.

“I loved her big heart,” Kyle says.

Kyle, then 30 and a wedding photographer, told Beth he’d bring her food when she started school. ” ‘I’ll bring you fries and dinner while you study and I won’t bother you at all,’ ” she remembers him telling her.

“He was so sweet and made a big effort to love everyone in my life, and that was important to me,” she said. “Kyle made me feel completely safe and respected.”

Kyle proposed on December 24, 2017, in Beth’s living room. She was stressed from studying for nursing school exams, with books and papers strewn around the room.

“She said that if I could love in the cycle of life she was in, [then] we should be able to make it through anything,” Kyle recalls.

Directly after the proposal, Beth and Kyle went to Christmas Eve services at Central Vineyard Church in Columbus and shared the exciting news with family and friends, jokingly inviting them to the “Long and Boring wedding,” which took place at the church in June.

Beth was now 29. They tried to start a family soon after, but after a year of trying, a doctor discovered that Beth had advanced endometriosis, and she had surgery in February 2020.

They then spent $15,000 on a round of fertility treatments that didn’t yield any viable embryos. A second round, at the same price, had the same result.

The process was grueling. Beth had to give herself shots of hormones, and for some of the treatments, they had to do a four-hour round-trip drive to the Cleveland Clinic. Between each round, they had to wait months to try again, with even more delays as doctors’ appointments often had to be canceled and rescheduled because of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Finally, a third round yielded three viable embryos: two boys and a girl.

“I just had a gut feeling we were supposed to transfer the girl” to her uterus, Beth said.

“She’s perfect!” the doctor said on September 20, 2022, just before he implanted the embryo into Beth’s uterus.

Inside her womb, the embryo was tiny and looked like it was blinking.

“She was just this little glowy dot on a screen, [and] she kind of looked like a shooting star, so we called her Star. She’s always been Star to us,” Beth said.

They waited seven weeks to see whether the implantation had worked.

“They did an ultrasound, and they confirmed her heartbeat,” Beth remembers. “The tech said it was perfect. Perfect heartbeat.”

“We’d finally made it to pregnancy,” Kyle said. “We’d spent years working on this, thousands of miles, thousands of dollars trying to get here, and it finally felt like it was worth it.”

Another ultrasound in December, when Beth was 16 weeks pregnant, also looked good, and they shared the happy news with their families at Christmas.

At that 16-week visit, Beth also had blood taken for routine tests.

They didn’t think much about that blood work until they received a phone call just after the new year.

‘Incompatible with life’

On January 4, the day before Beth’s 34th birthday, she received a call from her obstetrician.

“I could tell it was her serious voice,” Beth remembers. “She said, ‘Some of your lab work came back abnormal.’ ”

The doctor explained that the baby might have a neural tube defect, such as spina bifida.

Kyle started keeping a journal that day. “We are prepared to raise a child with any disabilities,” he wrote.

The next day, Beth’s birthday, “we meet with the genetic counselor, and she reassures us that she has seen a lot of fluke results and not to worry,” Kyle wrote.

And even if it wasn’t a fluke, “most potential issues seemed small. If there was a large issue, it could likely be fixed with surgery. It would require us to potentially temporarily move to a new city, but we both feel optimistic going into the scan,” Kyle wrote.

Still, “the scan felt like the longest 15 minutes of our life,” he wrote.

The ultrasound technician left the room and returned with a maternal-fetal medicine specialist, the genetic counselor and a nurse.

“We knew something was wrong,” Kyle wrote.

The doctor explained how the baby hadn’t developed a lower spine and the rib cage was large enough to hold only her heart, which was beating.

“There were organs outside her body. Her heart was inside her body, but it was abnormal,” said the physician involved with Beth’s care. “This is not compatible with survival.”

The doctor asked not to be named because the hospital where they work has not given them permission to speak to the media.

The Longs remember their doctors repeatedly using the phrase “incompatible with life” as they explained that the baby would probably die inside Beth or during birth.

At the ultrasound, the doctor “named a few more wrong things, but at that point I was more focused on Beth. At that moment we realized we were never going to have [our] baby girl,” Kyle wrote in the journal.

“We would have done anything to make her better,” Kyle said. But “there’s no surgery, there’s no magic pill that we could have done to make things better.”

The doctors assured the Longs that they’d done nothing wrong; Star’s rare condition was just by chance.

“We’re really good at winning the bad lottery,” Beth said.

The next day, the Longs met with Beth’s obstetrician. They said she explained that Star’s organs, besides her heart, had spilled out of a hole in her abdomen and were enmeshed in the placenta.

“[The doctor] explains to us that the sooner the pregnancy is ended the better it will be for Beth’s health. The longer the baby grows with these abnormalities, it will continue to have a worse and worse impact on Beth’s health,” Kyle wrote in his journal.

Beth said that if the placenta tore during the procedure, “I could have a lot of internal bleeding” because the bigger Star grew, “the more complicated and enmeshed [the placenta] was going to be, so time was of the essence.”

Shamshirsaz, director of the Maternal Fetal Care Center at Boston Children’s Center and a professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, noted that a 21-week fetus is significantly larger than a 17-week fetus, so the three-week wait put Beth at a higher risk for bleeding and other complications.

“We know in obstetrics if we can do [an] earlier termination, the outcomes will be better. That is set in stone,” he said.

Dr. Erika Werner is the chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Tufts Medical Center in Boston and a spokesperson for the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine.

“I’ve had lots of patients who never thought they would consider termination that have ended up terminating because of this diagnosis,” said Werner, who was not involved in Beth’s care.

Beth’s obstetrician said she wouldn’t be the one to do the abortion. She would reach out to one of the few specialists in Columbus who could do the complicated and risky procedure.

Over the next few days, the couple grieved for their lost baby daughter. As Kyle photographed a wedding, he watched little girls dancing with their dads during the father/daughter song, and he knew he’d never have that chance with Star.

They gave their baby a full name: Cordelia Poppy Star Long, with Star as a nickname because that’s what she looked like at the implantation and Corn Pop “because it was cute,” Kyle wrote in his journal.

While they waited to hear back from the obstetrician, Kyle called a local funeral home to arrange for Star’s cremation while Beth knit and crocheted tiny dresses for Star.

On January 9, three days after their appointment with the obstetrician, the Longs signed a form so they could officially begin Ohio’s 24-hour waiting period before an abortion.

The termination was supposed to take place in the next day or two, and while they dreaded it, they hoped it would mark the beginning of a recovery period, and then they try as soon as possible to implant one of their other two viable embryos.

But that didn’t happen.

Kyle wrote this in his journal: “Tuesday, 1/10 – The doctor calls and lets us know that none of it will be covered by insurance.”

‘It was horrifying’

The doctor explained that while it was legal for them to have the abortion, a 1998 Ohio law made it illegal for state employees’ insurance to cover the procedure except in certain narrow cases. The mother’s life being “endangered if the fetus were carried to term” is one of them, but the law doesn’t define what “endangered” means.

In his journal, Kyle wrote that the doctors gave them four options: One, pay the $20,000 to $30,000 and have the abortion right away in Ohio with the specialist their obstetrician had selected; two, wait until the baby died inside Beth, and then insurance would cover the abortion; three, wait until Beth’s life was at sufficient risk that the insurance would cover it; or four, find someplace else where they could do the procedure for less money.

“Kyle was ready to whip out a credit card” and pay for the procedure to be done soon at the hospital they were already familiar with in Ohio, Beth said.

“I was so motivated to just shell out the money and get it done,” Kyle added. “Just so it would be easy on us from a mental standpoint.”

Beth appreciated her husband’s efforts to protect her, but she wanted to save money for implantation of their remaining two embryos and for fertility treatments to create more embryos if those didn’t take. She’d already taken unpaid time off work during her pregnancy, and she was about to miss more work.

“For Beth it made more sense to put the focus on our future children,” Kyle wrote.

They decided to try the last option: finding a qualified doctor who would do the procedure for less money.

“It was horrifying because we were experiencing the hardest pain that anybody could have, and on top of that, of our grieving, we’re having to handle all of this ourselves and coordinate all of this ourselves,” Kyle said.

A race against the clock

Beth was now nearly 19 weeks pregnant. She and Kyle were racing against the clock.

Ohio law allows for abortions up to 22 weeks of pregnancy. Plus, with each passing day, the baby was growing larger, putting Beth at increasing risk of potentially deadly complications when it came time for the termination.

To spare Beth more anguish, Kyle made calls to Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio and various hospitals in the state. He wanted to be as close to home as possible so they could be near friends and family for support and so Beth wouldn’t have to endure traveling and staying at a hotel.

When he failed to find a place for Beth to have the procedure, he was once again resigned to putting it on his credit card.

But then he received a call back from Leah Mallinos, a social worker and patient navigator at Planned Parenthood of Greater Ohio. She said UPMC Magee Women’s Hospital in Pittsburgh would do the procedure for $2,500.

But it couldn’t happen immediately. There needed to be a virtual appointment with a Magee doctor and a transfer of medical records, and they needed to wait for availability at Magee.

While they waited, they grieved the loss of their daughter.

Beth bought a fetal Doppler to listen to Star’s heartbeat. She listened to it over and over.

“She had a good, strong heart. I was so proud of that heartbeat,” she said. “She had worked really, really hard to grow.”

On Instagram, Beth posted a video of the Doppler on her belly, recording Star’s heartbeat.

“I love her,” she wrote in the post. “And I refuse to let her suffer or be in pain for even a moment when she’s on the outside of me. Abortion is the most loving thing I can do for her as her mother, even if it shatters my heart.”

Beth prepared for her daughter’s death.

“I don’t think I’m ever going to forget the feeling of my baby girl kicking inside of me while I was looking for urns on the Internet for her ashes,” Beth said.

Still, she would have to wait another two weeks before she could have the abortion in Pittsburgh.

On January 23, she and Kyle made the drive, bringing with them for comfort Mr. Darcy, Beth’s dog of 11 years, and the dresses that Beth had made for Star.

The next day, they signed papers for Pennsylvania’s 24-hour waiting period.

Because Beth was so far along in her pregnancy – by this time, she was 21 weeks – it was a two-day procedure.

On January 26, the dresses Beth had made lay on her stomach as she was waiting to go into the operating room. Kyle kissed his wife’s head as she cried and then went to her belly to tell his daughter goodbye, that he loved her and that he was sorry he and her mother couldn’t save her life.

Heather Bradley, a doula who specializes in helping grieving parents, took close-up pictures of Star’s feet wrapped in one of the dresses Beth had made.

Bradley, founder of Pittsburgh Bereavement Doulas, said she is usually able to control her emotions even in the saddest of situations, but this one was different.

“I felt myself tearing up,” she said. The Longs had made “the worst decision anyone ever has to make, and then to deal with all the other logistics they had to deal with was just ridiculous.”

She said the Longs were “hanging by a thread” after the procedure as they headed back to Columbus.

“They’re traveling in a car for [three] hours after having an abortion. Things can happen. You should be resting and being monitored, sleeping, letting your body heal. You shouldn’t have to be worrying about where we’re going to stop to eat or the expense.”

Planned Parenthood gave the Longs $500 for the hotel and the Abortion Fund of Ohio gave them $1,800 toward the $2,500 hospital charge for the procedure, but the Longs say they paid $1,150 out of pocket, which included the rest of the hospital charge and travel expenses. In addition, they expect bills from the anesthesiologist and other specialists involved in the procedure.

“It was a tough drive. We drove there with our child, and we were driving home without her,” Kyle said.

Reaching out to lawmakers

Kyle has reached out to his elected representatives, including Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine and Sen. JD Vance, both Republicans.

He told them that Ohio law had “turned a difficult situation into something nearly unbearable.”

“I am a lifelong Republican, but this has turned me into a one-issue voter for those that support reproductive rights.”

“I’m writing you to please reconsider how you approach reproductive rights going forward. There are a lot of unintended consequences for families from these laws, and while I can understand you come from a good place, care should ultimately be left to the parents and their physicians. We loved our baby girl and would have done anything to keep her,” he wrote, adding that Ohio abortion laws “prevent grieving parents from the healthcare they need.”

He says he never received a response from either DeWine or Vance.

Spokespeople for DeWine and Vance told CNN that they plan on responding to Kyle’s email. DeWine noted that the law banning state insurance from paying for abortions was enacted before he took office.

A spokesperson for Beth’s workplace, which owns the insurance plan, says it will continue to comply with the law while providing exceptional patient care.

Beth belongs to the Ohio Nurses Association, a union affiliated with the American Federation of Teachers.

What happened to Beth is “an abomination,” federation President Randi Weingarten said. “The results of not getting proper and timely care due to egregious systemic roadblocks and financial constraints not only causes bodily harm but trauma that will last a lifetime.

“Reproductive care must be a decision that belongs between a patient and a doctor, not with politicians,” she added.

Trying to help others

Nearly two weeks after the abortion, Beth and Kyle are filled with both grief and anger.

“We wanted more than anything to have this baby, and the laws in place prevented us from getting the proper health care that we needed,” Kyle said. “It delayed us being able to lay [Star] to rest and grieve our baby for three weeks.”

As soon as Beth’s doctors tell them it’s OK, they plan to implant one of their two remaining embryos in the hopes of starting a new pregnancy.

In the meantime, they’re mourning Star and want to help other families who might be in their situation.

First, they want them to know that there are resources to help, such as Planned Parenthood and groups like the Abortion Fund of Ohio.

Second, they’re reaching out to state legislators who support the “heartbeat bill” that passed the Ohio legislature in 2019. It banned nearly all abortions after fetal cardiac activity is detected, about the sixth week of pregnancy, but a judge in Cincinnati issued an injunction in October, and now in Ohio abortion is allowed up to 22 weeks.

They say they hope their story will help change legislators’ minds.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“I don’t want any other families to have to go through this,” Kyle said. “I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy, and something needs to change,”

Beth adds that she thinks all women should have the right to an abortion, not just women like her whose babies have fatal abnormalities.

“It was the most dehumanizing experience of my life,” she said.

CNN’s John Bonifield and Nadia Kounang contributed to this report.