Every Q-tips box has a warning label: “Do not insert swab into ear canal,” and if you’re going to use it to clean your ears, gently swab the outer part only.

But extracting wax from our ear canals is precisely why most of us buy Q-tips in the first place. The humble Q-tip was so perfectly designed for this purpose that it turned into a generic word for a product.

Yet, somehow, we use it for the very thing it specifically warns us not to do.

‘Q-Tips Baby Gays’

The origins of this strange consumer phenomenon can be traced to Leo Gerstenzang, an immigrant from Poland.

In 1923, Gerstenzang supposedly thought he could improve upon his wife Ziuta’s method of wrapping a wad of cotton around a toothpick to clean their newborn daughter Betty’s eyes, ears, belly button and other sensitive areas during bathing.

Gerstenzang started a company that year to develop and manufacture the first ready-made sterilized cotton swabs for baby care. Over the next couple of years, he worked to design a machine that could produce swabs “untouched by human hands.”

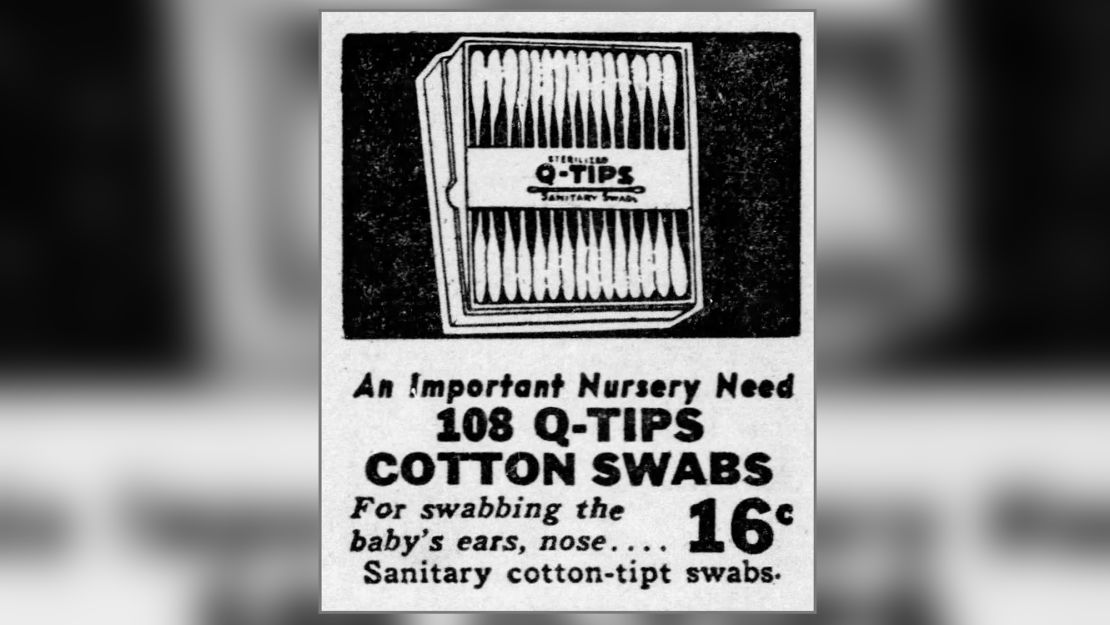

“Baby Betty Gays” was the original working name for the swabs because daughter Betty laughed when her parents tickled her with them, according to her 2017 paid obituary. By the time Gerstenzang put out one of the first newspaper advertisements for his invention in 1925 it was shortened to “Baby Gays.”

Soon, Gerstenzang changed the brand name to “Q-Tips Baby Gays.” By the mid-1930s, “Baby Gays” was dropped from the name.

There are competing histories to where the “Q-tips” addition came from. According to a spokesperson for Unilever (UL), the consumer goods conglomerate that bought Q-tips in 1987, the “Q” stands for “quality” and “tips” describes the cotton swab at the end of the stick (the first swabs were single-sided sold in sliding tin boxes).

But, according to Betty’s obituary, “Q-tips” was a play off “Cutie-Tips” because she was so cute as a baby.

‘Adult ear care’

Q-tips never told us to stick the swabs in our ear canal to clear out earwax. But, from its beginning in the 1920s, it made ear care a key focus of its marketing strategy. This trained generations of Americans to associate it with cleaning there.

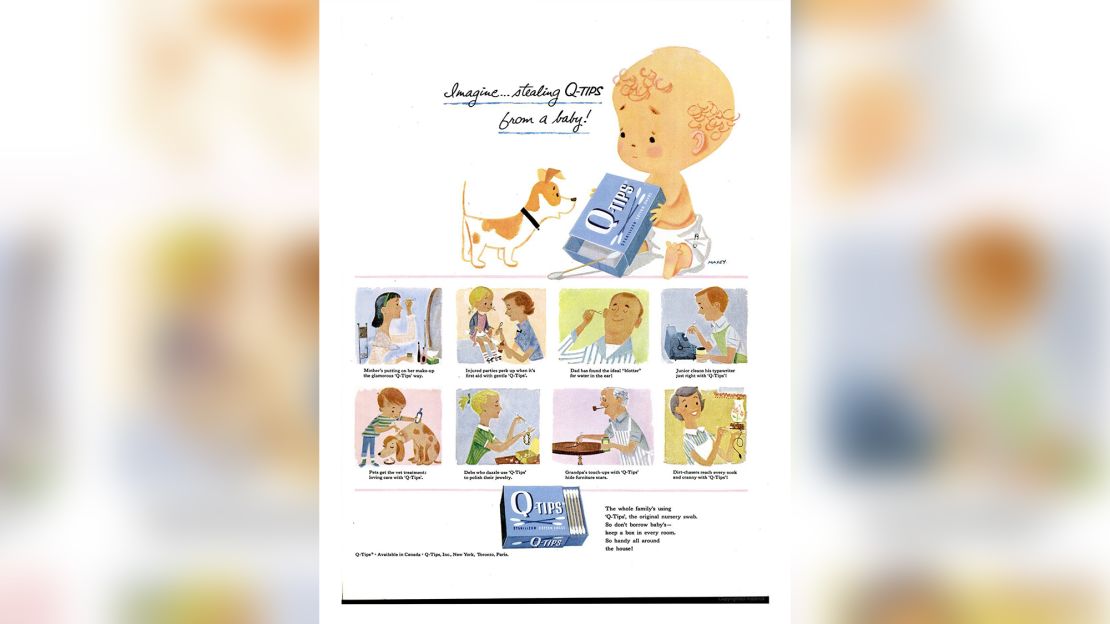

Mid-century advertisements often featured illustrations of men and women cleaning their ears or their babies’ ears with them, including one depicting a man removing water from his ears after a swim.

Old versions of boxes listed “adult ear care” as a main use for the product.

Even Betty White later appeared in television spots for Q-tips in the 1970s and 1980s, promoting them as the “safest and softest” swabs on the market for your eyes, nose and ears.

Q-tips are almost addicting to use to clear out wax and it becomes a vicious cycle when we do so, said Douglas Backous, a neurotologist specializing in treating ear and skull conditions. Removing earwax creates dry skin, which we then want to scratch with — of course — a Q-tip.

Sticking Q-tips in your ears also can damage the ear canal. Most people do not actually need to remove earwax, as well, because ears are self-cleaning. Inserting a swab can traps earwax deeper inside, he said, and “you’re actually working against yourself by using it.”

It wasn’t until the 1970s, under previous owner Chesebrough-Pond’s, that Q-tips added a warning about not sticking the thing in your ear. It’s unclear what prompted this change.

“The company has no details on why they did this, and our search of the records turns up no publicized case of anyone with a swab in the brain,” the Washington Post reported in 1990. “Something must have happened, and Chesebrough-Pond’s didn’t want to be blamed.”

But by the time Q-tips added that warning label, it was too late. Consumer habits had become impossible to break, and Q-tips controlled around 75% of the market for cotton swabs.

“It was just accepted that that’s how people were using it,” said Aaron Calloway, the Q-tips brand manager at Unilever in 2007 and 2008.

‘Beauty assistant’

So what should you use Q-tips for? The company has several suggestions. For decades, it has tried to emphasize the versatility of cotton swabs.

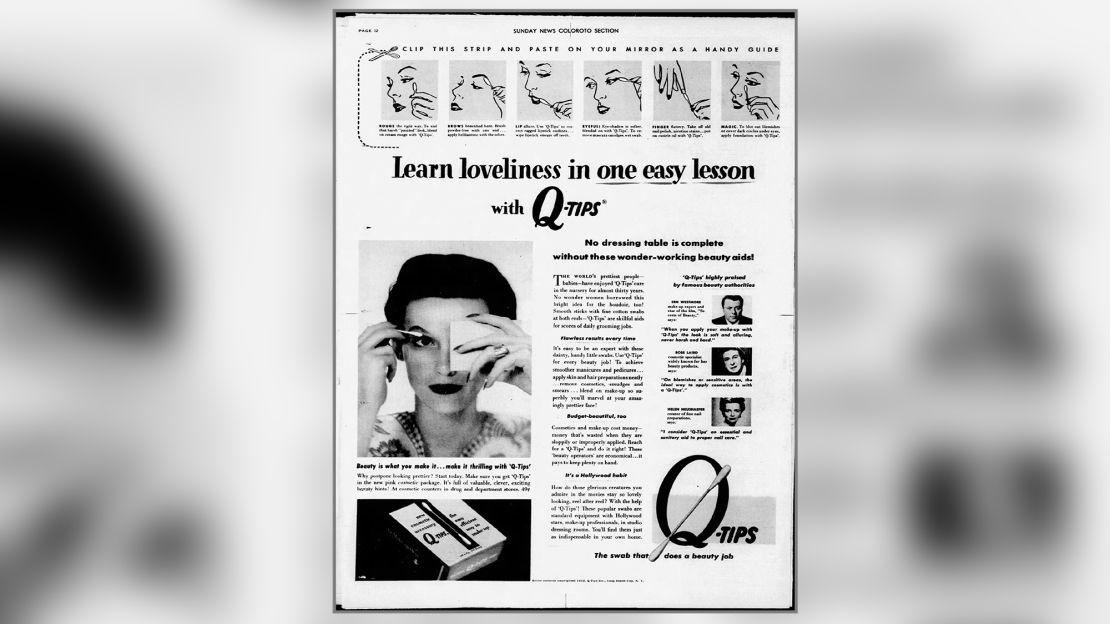

During the 1940s, Q-tips were positioned as an essential tool for women’s cosmetics and beauty routines.

“Mommy, do you know you can use Q-tips for many things?…You can use them yourself when using cream or make-up, too mommy!” read a 1941 print advertisement.

Another print advertisement, a decade later, described Q-tips as a “beauty assistant” for women.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Q-tips began to tell consumers they were for more than just for babies or women – they were handy for just about any project around the house or in their lives.

“For lubricating power saws and drills…guns and fishing reels…mending a tea cup and cleaning jewelery…Antiquing furniture,” read a 1971 ad.

Today, there are no ears in Q-tips’ advertising. A spokesperson for the brand says 80% of consumers use Q-tips for purposes other than personal care.

CNN’s Leidy Cook contributed to this article.