Editor’s Note: Lindsay M. Chervinsky, Ph.D. is a presidential historian and a Senior Fellow at the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University. She is also the author of “The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution” and can be followed on Twitter @lmchervinsky. The views expressed here are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

July 4th is always a moment to consider what it means to be an American – and who counts as a citizen – but this year also offers a unique opportunity to consider the holiday’s legacy and how we might live up to its potential. As the country continues to grapple with the systemic racism inherent in so many of our political and social institutions, we cannot overlook the persistent second-class status of Puerto Rico, Guam, the American Virgin Islands and other US territories.

From 1898 to 1917, the United States acquired territory in Puerto Rico, Guam, the American Samoan islands, and the Virgin Islands through peace settlements ending the Spanish-American War, military conquest, and a purchase from the Kingdom of Denmark. Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands and Guam all remain unincorporated territories.

The history of US White supremacy lingers at the center of these territories’ legal status. Nothing is more fundamental to citizenship than equal rights under the law, but for the last century, citizenship in these territories has been limited and conditional – an institutional vestige of imperialist decisions made in the past because of race and ethnicity and reinforced by politicized racism today. The federal government must offer full and complete statehood or independence to the residents of these territories. The choice of whether to accept it should be theirs, as it should have been 100 years ago.

Washington DC is another key example that comes to mind, with nearly 700,000 citizens living in the Federal District. They pay federal taxes, yet they are not fully represented in Congress. The District has one delegate, with limited voting privileges, and no senators representing its interests.

Washington has advocated for full statehood as well and has found strong support among some Democratic lawmakers. Efforts to obtain DC statehood have stalled in the Senate, however, largely because of Republicans’ fear of losing political power, since the District’s predominantly Black population reliably swings overwhelmingly Democratic. But it’s not the only territory with limited status. Guam, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, American Samoa and Northern Mariana Islands are all technically affiliated with the United States or part of the Union but exist as second-tier territories.

This week is the perfect opportunity to consider full citizenship for residents of these territories. The Biden administration is, an official told CNN, introducing a strategy to “encourage US citizenship” for eligible immigrants. What about those living in these territories? Meanwhile, voting rights are very much also in the news with state legislatures around the country passing restrictive voting laws which will make it more difficult for communities of color to access the ballot boxes. Look no further than Thursday’s Supreme Court decision upholding voting restrictions in Arizona. These measures and recent developments have been met with appropriate outrage on the left, but deafening silence largely persists about those in US territories and limitations on their citizenship.

In all, over 3.5 million people live in these territories but don’t enjoy the full rights and benefits of citizenship. For example, many Puerto Ricans pay federal taxes, but they can’t vote in US presidential elections, nor can they elect representatives or senators for Congress.

As nationals, American Samoans have a looser legal relationship with the United States, but no less commitment to patriotic service. American Samoans enlist in the military at a higher rate than citizens from any other US state or territory. The territory is largely self-governing by its own governor and legislative body but remains under the auspices of the secretary of the interior, who retains the power to approve constitutional amendments, override the governor’s vetoes and reject the nomination of judges.

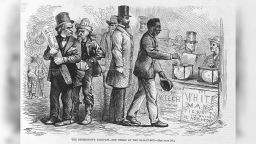

Why do these weird, antiquated territorial designations even still exist? White supremacy. In 1899, the United States began to seek additional territories beyond the continental borders, scooping up imperial acquisitions in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean. But these acquisitions provoked an identity crisis. Historian Daniel Immerwahr, in his book “How to Hide an Empire,” has demonstrated how three core values dominated the political landscape at the turn of the 20th century: imperialism, White supremacy, and republicanism (not the Republican Party, but rather the belief in self-government). Those three values proved to be incompatible with one another.

In the 19th century, the federal government lured White settlers to new territories with the offer of cheap land seized from Native nations. Once enough settlers had arrived, they formed a provisional government and a proposed state constitution, which Congress usually accepted as a new state.

For example, in 1820, Congress accepted a compromise that admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state to retain the balance of power between the North and the South. But that same process didn’t apply to the territories acquired beyond US borders. White settlers weren’t interested in residing in many of the more tropical regions, nor did most officials think natives could manage self-government.

For example, Secretary of War Elihu Root argued that Puerto Ricans couldn’t be trusted with republican government until they learned “the lesson of self-control and respect for the principles of constitutional government;” a process he expected to take some time, as “they would inevitably fail without a course of tuition under a strong and guiding hand.” As Immerwahr writes in his book and discussed with me in a podcast interview, many congressmen also didn’t want brown or Black colleagues sitting in the storied desks in the Senate chambers.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Accordingly, the US government had three options: they could maintain their White supremacy and imperial designs but would have to abandon their republican values; they could retain their White supremacy and republican values but would have to abandon their dreams of empire; or they could still expand their territorial holdings and encourage republican self-government but would have to welcome new governments run by non-White citizens as their equals. Perhaps unsurprisingly, republicanism was the easy target.

Over a century later, these warring impulses still divide this nation. The federal government still wants to retain control and access to territories across the world, but many political figures oppose including them in the Union as equal members. If we share the streets of DC with fellow Washingtonians, we trust American Samoans to serve in our military, and we expect Puerto Ricans to contribute to the national budget, surely, we can extend the benefits of citizenship. We can acknowledge our imperial past and grant full independence or complete statehood.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly dated the time period over which the US acquired its unincorporated territories. It was from 1898 to 1917.