When Sorawut Kittibanthorn describes his innovative protein alternative, it’s mouth-watering.

“High-quality meat is tender and juicy – it has a melt-in-the-mouth texture,” says Kittibanthorn. “So I wanted my meat to have these aspects.”

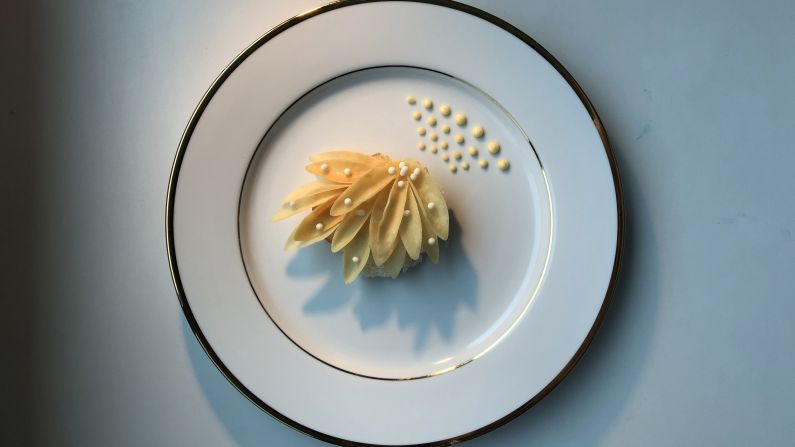

Visually, the meat substitute lives up to the description: it’s used to make a rich, red, raw-looking “beef tartare” and a salt-water infused “fish fillet.” Delicately plated, the dishes wouldn’t look out of place in a chic Manhattan restaurant.

But the protein’s central ingredient is more often found in landfills or on the kill floor of slaughterhouses: chicken feathers.

The human body can’t digest feathers, but they are 90% keratin – a protein that’s found in nails and hair – and packed with nutritious amino acids. Kittibanthorn makes feathers edible by breaking down the protein using a process called acid hydrolysis.

The protein was created earlier this year for Kittibanthorn’s Material Futures master’s project, “A Lighter Delicacy” at London’s Central Saint Martins art school. With roughly two million tons of chicken feathers discarded every year, the Thai design student wants to challenge the perception of what’s considered waste – and showcase the potential of this unusual ingredient.

Changing perceptions

In 2018, a study of keratin extracted from poultry feathers tested its use as a sports supplement. While researchers found that it didn’t boost performance in athletes, it did increase users’ lean body mass.

It was this high-value protein content that first got Kittibanthorn’s attention. Partnering with food scientist Keshavan Niranjan from the UK’s University of Reading and biology lab technician Shem Johnson from Central Saint Martins, he developed a 13-step process to break down the feathers into a digestible form.

The feathers are cleaned, pulverized and placed in a water bath with acid and keratinase – an enzyme that severs keratin’s strong chemical bonds. The solution is gently heated and constantly stirred for 12 to 24 hours, before being filtered and cooled.

In his experiments with the feather-based protein, Kittibanthorn created carb-free pasta and wraps, and protein bar biscuits. He also tested different binding agents to create a texture, color and consistency that would mimic high-quality meat. The feather “meat” has no taste, says Kittibanthorn, and relies on seasoning for flavor.

After winning the Mills Fabrica Techstyle Prize this summer, Kittibanthorn is hoping to collaborate with chefs on recipes, as his next step, he says.

Trash to treasure

Around 10% of a chicken’s weight is its feathers. Most end up in landfills where they can cause environmental issues like soil and water pollution, while some are incinerated, contributing to global carbon emissions.

This huge amount of waste creates an opportunity for those embracing a zero waste mentality – and Kittibanthorn isn’t the only one to see it.

Swedish biotech startup Bioextrax converts feathers into a digestible, high-protein animal feed using a microbe-based hydrolysis process to break down the keratin.

The chemical and physical properties of feathers mean they have a lot of other potential uses, says the company’s CEO, Edvard Hall, adding that Bioextrax is also conducting research into feather-based bioplastics and insulation material.

Hall says Bioextrax hopes to license its technology to slaughterhouses and waste management companies to help them create a “circular protein system.”

While the company has pursued turning feathers into animal feed because the market is more “straightforward,” Hall says there’s no reason that it couldn’t also work for people. “It could be used as a protein supplement for humans, without any changes in the process,” he says.

Cultural perceptions are still a barrier, though. Hall compares the feather-based protein to food made from insects, and says that “some people might find it a bit disgusting.” Additionally, as it’s derived from animals, it misses out on the vegan market. But in the long run, he doesn’t see this as a problem.

“It derives from something that is currently being thrown away and not utilized,” says Hall, “so from a sustainability perspective, it’s definitely a good protein source.”

Another challenge is legislation. In the EU, new food products need to undergo extensive analysis and risk assessment, and it can take up to nine months to obtain authorization.

While we might not be seeing chicken feathers on our dinner plates any time soon, Kittibanthorn hopes his novel approach to waste and the elegant presentation of the sample dishes will help people accept quirky ingredients like feather “meat.”

The technology is out there already, he says, but our attitude and approach to waste in the food ecosystem needs to change. Zero-waste food products like the feather protein are a “symbol” of how we can improve the the future, says Kittbanthorn.

“It’s showing empathy for the world,” he says. “It’s showing what we stand for.”