It started out as a project for National Science Week at his children’s British primary school – a way malaria researcher Jake Baum could teach the kids the difference between a herbal remedy and true medicine.

“So if my mum or my grandma says they’re going to give me this tea and it’ll make me better, and somebody comes along saying, ‘Oh, that was just hocus pocus, I’ll give you a real medicine,’ what’s the difference?” asked Baum, who is a professor of infectious diseases at Imperial College London.

“We decided the difference is evidence: If you take a natural remedy and you test it and it works, it’s now also a medicine,” Baum said. “So we came up with the soup project. We asked kids to bring in the traditional soup their family would make when someone was not feeling well.”

The soup project

Sixty soups arrived, all incredibly diverse. Children of Eden Primary School, which Braum’s son Gilly and daughter Rudy attended, caters to families from across Europe, the Middle East and North Africa.

All were supposed to be broth-based vegetarian, meat or chicken soups that the family had passed down through the generations because of their restorative properties.

“Kids bought in the lumpiest soups even though we told them not to,” Baum said. “The idea was to try and get some kind of clear extract from it.”

Which soup did he think would win? His Jewish family’s chicken soup, “designed to cure all aliments,” he said. After all, there is some science behind the idea that chicken soup can cure a cold.

Working with the children, Baum was able to successfully filter 56 of the soups, which he took back to the lab to test for their medicinal attributes.

A deadly parasite

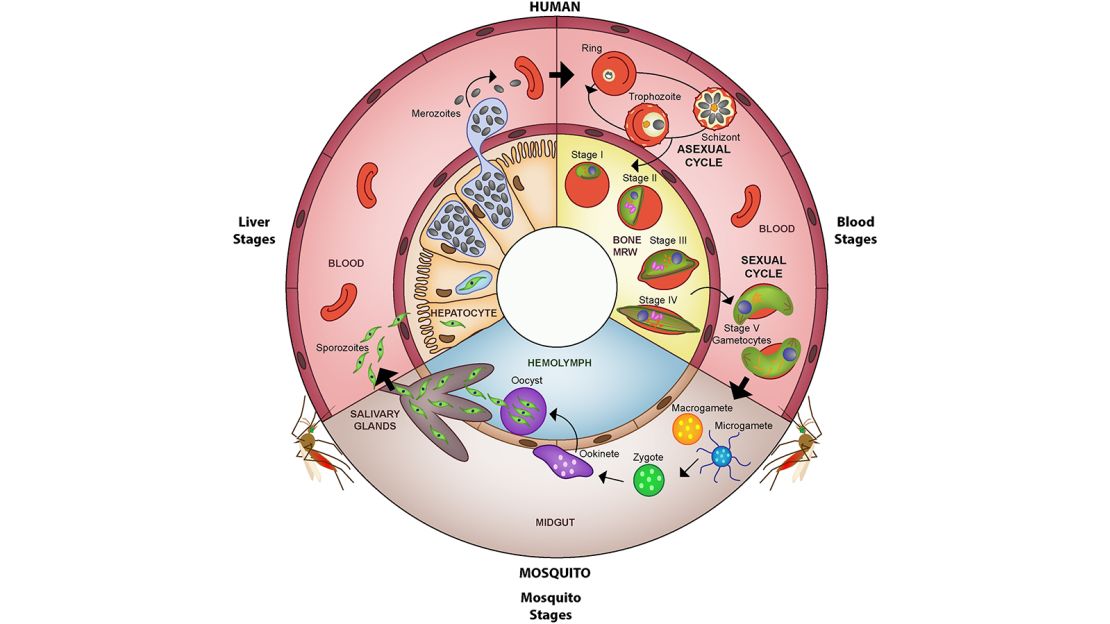

What would be the test? Why malaria, of course, since that is Baum’s life’s work. He and his team at the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial College study the most deadly species of malaria parasite, called P. falciparum, responsible for 99% of malaria deaths.

According to the World Health Organization, in 2017 there were an estimated 219 million cases of malaria transmitted by infected mosquitoes in 2017, affecting 87 countries. There were 435,000 deaths that year as well.

Every year, nearly half a million children die from malaria transmitted by infected mosquitoes, Baum said. Most are under five years old.

“We’re currently at a sort of crossroads in global malaria control,” Baum said. “We’ve had decades of progress in reducing the number of deaths from the turn of the millennium. But we’ve kind of reached this point where we sort of stalled in our progress and there are some worrying signs of emerging drug resistance, just like you have antibiotic resistance to bacteria.”

Even the frontline antimalarial drugs, called artemisinin-based combination therapies, or ACT, are beginning to lose their effectiveness as the parasite evolves resistance.

“The malaria parasite is one of the very ancient parasites,” Baum said. “It’s a very complicated creature: it can change its shape, it can change its biology, and that makes it much harder to develop new drugs and new therapeutics.”

A surprising result

At first, Baum and his team didn’t plan to carry out all 56 tests; after all, no one expected a soup to kill a malaria parasite.

“We thought we’d just give it a go,” Baum said. “And we were quite surprised, a few of the soups had really good activity against the parasite.”

In fact, five of the 56 soups blocked parasite growth in the human blood stage by about 50%; two of those were as effective as a leading antimalarial, didydroartemisinin. Four other broths were able to block the male parasite’s sexual development by around 50%.

“One of the soups that was most effective was a vegetarian soup with a fermented cabbage base,” Baum said. “And you know, people do sing the praises of kimchi and other fermented cabbages, so maybe there’s something in that.”

Baum published the soup project results Monday in the journal BMJ. Will he go on to discover the antimalarial ingredients in the soups? No, that project is for others, he said.

“There are a lot of people working on testing purified natural products that have been taken from plants, from traditional remedies. Every now and then you come upon something that really works,” Baum said.

One of the challenges, he continued, is that plants make extremely complex molecules science can’t yet synthesize, much less deliver in the massive scale needed to combat worldwide malaria transmission.

“But that shouldn’t deter us from looking,” Baum said, pointing to his simple elementary school experiment.

“It just shows that there may be medicines yet to be discovered and we shouldn’t turn our eyes up at traditional medicine just because it’s not tested yet.”