Editor’s Note: Karen Karbiener is a Walt Whitman scholar who teaches at New York University. Her works include an edition of “Leaves of Grass,” a book introducing children to Whitman’s poetry, and “Live Oak, With Moss,” an edition of Whitman’s secret same-sex love poems illustrated by Brian Selznick. She is president of the Walt Whitman Initiative, and is spearheading the campaign to grant landmark status to Whitman’s only standing residence in New York City (99 Ryerson Street in Brooklyn). The views expressed in this commentary are her own. View more opinion on CNN.

This week marks the 200th birthday of Walt Whitman (1819-1892), often referred to as “America’s Poet.” But what are we celebrating, and why does Whitman deserve this title?

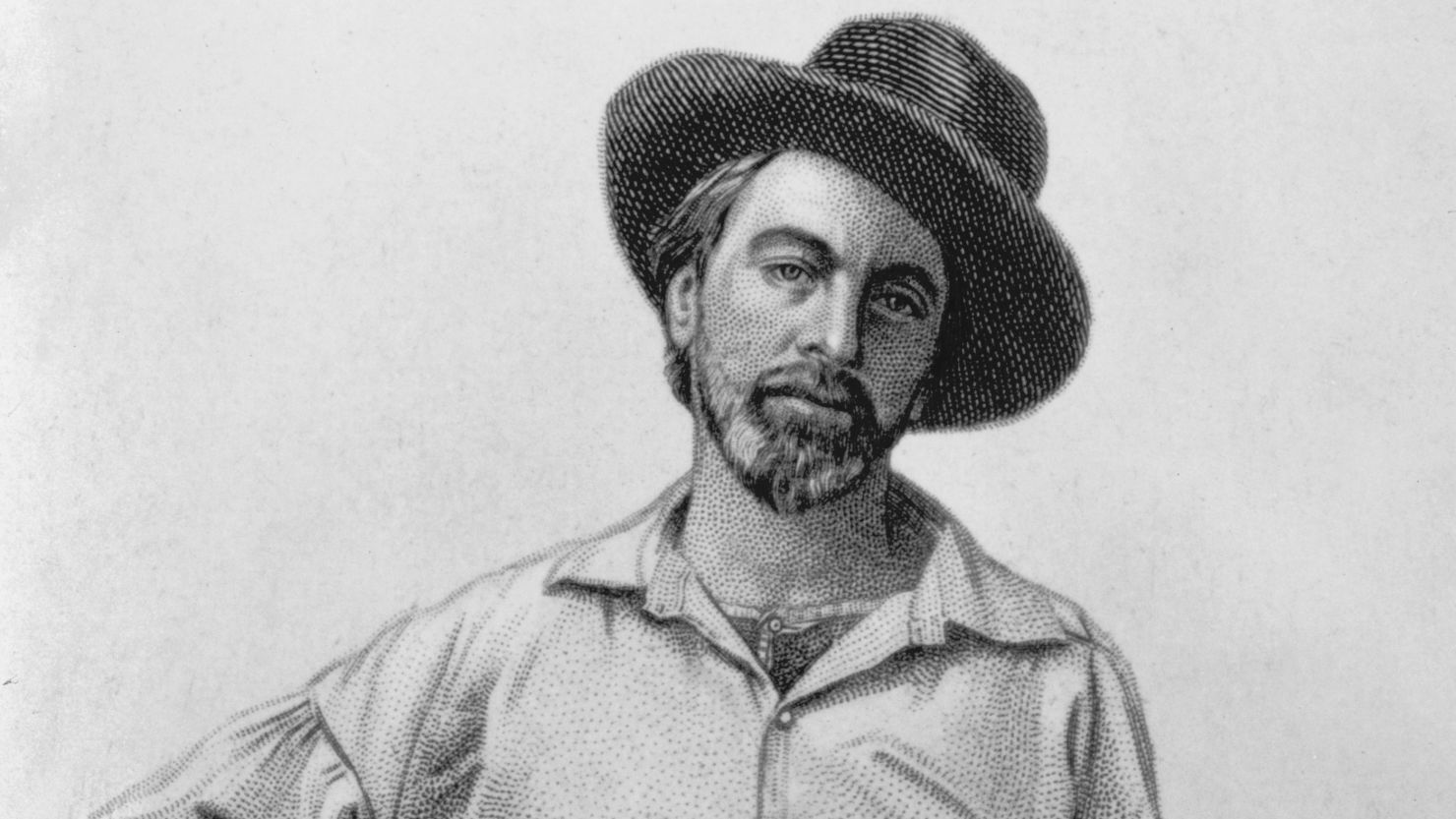

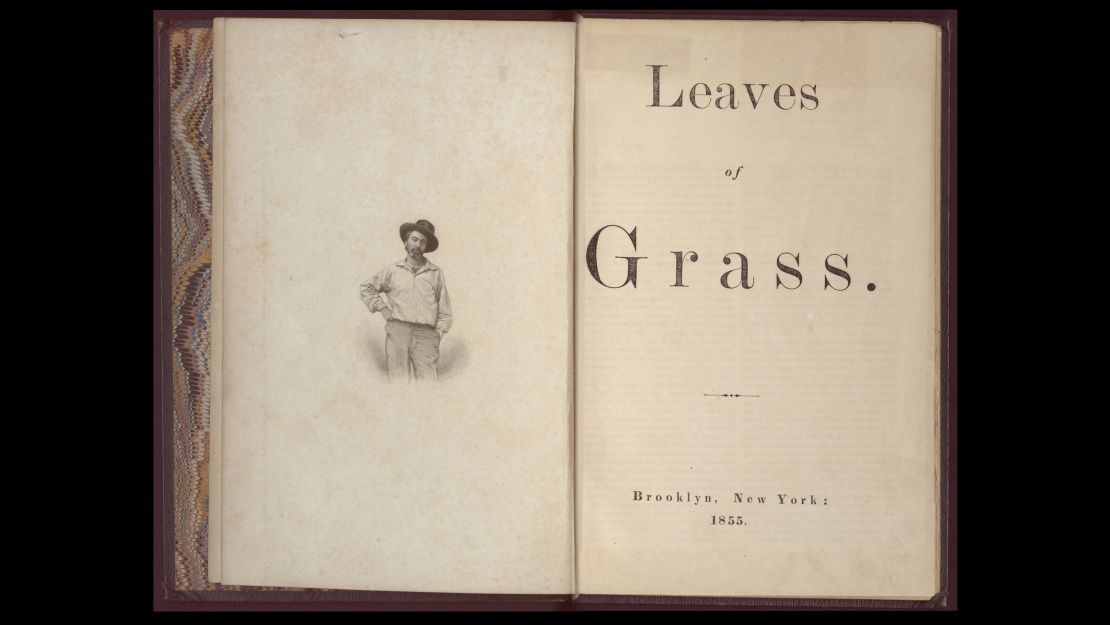

Around 1890, Thomas Edison allegedly recorded Whitman declaiming his poem “America.” That voice is known by millions of people, thanks in part to a massive advertising campaign for Levi’s jeans. As the 1855 frontispiece image of Whitman has become iconic, so have his words. They have been reprinted in thousands of books in hundreds of languages and have shaped the ideas of “old and young, the foolish as much as the wise.”

Today, Whitman helps sell Brooklyn-made ice cream, luxury cars and at least nine types of beer. His words are quoted by presidents, poets and celebrities (Madonna, Lana del Ray, Iggy Pop, Tupac Shakur and, yes, even Bill Murray). They are carved into stone in Canada’s Bon Echo Provincial Park, displayed under his towering bronze likeness in Moscow, and around the New York City AIDS Memorial. And the conversations they sparked on democracy, freedom, and humanity’s common bonds still fire hearts and minds. Walt Whitman and his words are with us — even a little ahead of us.

At the same time, this bicentennial moment is not the moment for uncritical hero worship. It is an occasion to reflect on what being “America’s Poet” actually means. To celebrate Whitman as the poetic embodiment of unsettled democracy must also be to acknowledge his stature as an exemplar of the long history of America’s political polarization. Whitman represents the most inclusive — and the most insidious — aspects of our national character.

Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” (1855) is, in many ways, our cultural declaration of independence. It paved the way for a distinctly American literature at a time when the United States was still fumbling to forge a national identity on the world stage. Between the book’s covers, 12 unrhymed, unruly poems celebrate America as a “teeming nation of nations” — a community of equals across race, gender, economic class, politics and sexual preference.

Whitman, in many ways, lived out that radical vision of equality in his poetry and in his life. Decades before the word homosexual was in common parlance, over a century before the dawn of America’s organized LGBTQ movement, whose work we honor with Pride Month in June, Whitman declared his intention to “celebrate the love of comrades” and to establish a community of same-sex lovers in the “Live Oak, With Moss” and “Calamus” clusters of poems.

Befriending activists, including Abby Hills Price and Paulina Wright Davis at the very start of the women rights movement, Whitman also wrote poems that honored women’s central role in the establishment of a democratic society and demonstrated that the female body — and even female desire — are fitting subjects for poetry (consider the enduring shock value of “Unfolded Out of the Folds,” an extended meditation on the physicality of birth and sex, and the “28 Bathers” passage of “Song of Myself,” in which one woman fantasizes about not one but 28 potential partners).

More generally, Whitman trained his poetic eye on those left marginalized by society. He defended “the rights of them the others are down upon” (to quote Section 24 of “Song of Myself”) by breaking long-held literary convention. He got personal with readers instead of maintaining a safe distance across the page and liberated poetry from rhyme and meter, writing in long lines that sound — even look — natural and free.

His radical democracy represents the Whitman many of us know and love. And yet in recent years, an important conversation has developed about another Whitman — for some an unfamiliar voice, one easier to dislike. While he equally considered “red, black, or white” in such poems as “I Sing the Body Electric,” openly defied the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act in Section 10 of “Song of Myself” and portrayed the righteousness of active vengeance against slavery’s supporters in 1855’s “The Sleepers,” some of his prose writings and statements made later in life denigrate African Americans in a way that can only be described as racist.

He seems to have been captivated by racist pseudoscience after the Civil War, and while he opposed slavery, he defended the exclusion of black Americans from Western territories of the United States.

After a music student at Northwestern University refused to perform a setting of Whitman’s “I Hear America Singing” because he declared the poet racist, others have either denounced Whitman or tried to understand why he would have penned and said such lines. Their efforts to grapple honestly with Whitman’s legacy on race has posed the question, as an essay in JSTOR Daily put it: Should Walt Whitman be “cancelled?”

I recently debated this question in a panel discussion with poets and activists at the Brooklyn Public Library. The discussion was open, charged and swelled to anger at times. Can we attribute it to the inherent racist attitudes of his time, the same racism we can also recognize in the words and deeds of significant 19th-century figures like Abraham Lincoln and Harriet Beecher Stowe? And who can we believe in if our so-called poet of democracy may not have been so radically democratic after all?

For me, the answer is to approach Whitman and his work not as a hero or a villain but as a mirror. “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes),” announces the narrator of “Song of Myself.” Walt Whitman the man was as conflicted and complex as the country he sought to embody.

He may still be regarded as a representative American — but representative of who we have been and continue to be, not just who we claim we are (“His crudity is an exceeding great stench, but it is America,” announced Ezra Pound, himself an anti-Semite, misogynist and fascist). When examining Whitman’s racial slurs alongside his most egalitarian poetic lines, we should feel discomfort and regret and the need for renewal and change.

This complicated and conflicted American also envisioned, described and celebrated a truly democratic society that neither his era nor our own has yet realized. What could America need more right now than a poetic figure whose work spotlights the chaos and division that have long defined what it means to be an American?

It is this voice that we honor this year, the voice that sympathetically pondered, “What is it then between us?” in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” We honor the creator of a passionately political 52-section “Song of Myself” that dreamed of “form and union and plan” for a nation at the brink of civil war — and when that hope was dashed, spent years tending wounded soldiers and writing hundreds of letters to their families.

We honor the open-hearted, all-embracing poems that will be read, recited, and discussed more this year than ever before — from Los Angeles to the UK, in the Great Hall and in our greatest cemeteries, on bridges, beaches and canoes, by everyone from Patti Smith and Robert Pinsky to you and me.