The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention warned US consumers on Tuesday to not eat romaine lettuce, as it may be contaminated with E. coli.

Thirty-two people, including 13 who have been hospitalized, have been infected with the outbreak strain in 11 states, according to the CDC. One of the hospitalized people developed hemolytic uremic syndrome, a potentially life-threatening form of kidney failure. No deaths have been reported.

People have become sick in California, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Ohio and Wisconsin.

The Public Health Agency of Canada has identified an additional 18 people who have become sick with the same strain of E. coli in Ontario and Quebec.

The US Food and Drug Administration, which is also investigating the outbreak, cautions that if you have any romaine lettuce at home, you should throw it away, even if you have eaten some and did not get sick.

FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb said Tuesday that it is “frustrating” that the FDA cannot tie the outbreak to a specific grower, but “we have confidence that it’s tied to romaine lettuce.”

“Most of the romaine lettuce being harvested right now is coming from the California region, although there’s some lettuce coming in from Mexico,” he said.

All brands and types of romaine lettuce

No one distributor or source has been identified, so the FDA is warning consumers to avoid all types and brands of romaine lettuce, Gottlieb said. Consumers should not eat any romaine lettuce product, including “whole heads of romaine, hearts of romaine, and bags and boxes of precut lettuce and salad mixes that contain romaine, such as spring mix and Caesar salad.

Retailers and restaurants also should not serve or sell any until more is known about the outbreak.

Illnesses in the current outbreak started in October, and it is not related to another multistate outbreak linked to romaine lettuce this summer.

A similar outbreak caused by contaminated romaine lettuce occurred in December, Gottlieb said, and affected the United States and Canada. “The strain in 2017 is the same as the strain in this fall 2018 outbreak, and the time of year is exactly the same. So It’s likely associated with end of season harvest in California,” he said.

What’s different this year is that the FDA has higher confidence that it’s romaine lettuce in both countries. “This year, we’re a month earlier, so we’re earlier in the process, earlier in the throes of an outbreak,” Gottlieb said. “So we’re able to actually get real-time information and conduct effective trace back and isolate what the source is.”

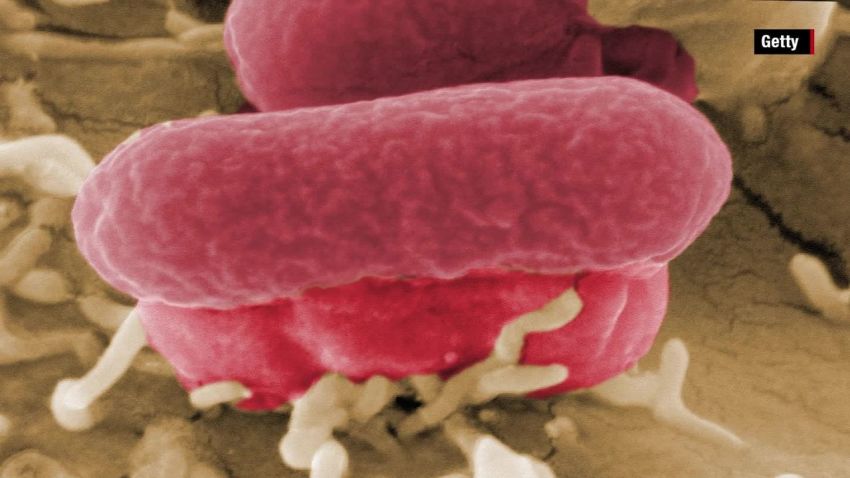

Symptoms of E. coli infection, which usually begin about three or four days after consuming the bacteria, can include watery or bloody diarrhea, fever, abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting, according to the CDC. Most people infected by the bacteria get better within five to seven days, though this particular strain of E. coli tends to cause more severe illness.

People of all ages are at risk of becoming infected with Shiga toxin-producing E. coli, according to the US Food and Drug Administration, which is also investigating the outbreak. Children under 5, adults older than 65 and people with weakened immune systems, such as people with chronic diseases, are more likely to develop severe illness, but even healthy children and adults can become seriously ill.

“That’s why we think it’s critical to get this information out,” Gottlieb said. “We understand fully the impact this has, not just on the growers and the distributors but also on consumers – consumers who are preparing meals for the holidays, who have product now that they’re going to need to discard, maybe food that they’ve already cooked.”

How does the US prevent foodborne illness?

Foodborne illness hits one in six Americans every year, the CDC says, estimating that 48 million people get sick due to one or another of 31 pathogens. About 128,000 people end up in the hospital and 3,000 die annually.

Preventing foodborne illness in the United States is the job of the US Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, which oversees the meat, poultry and processed egg supply, and the FDA, responsible for domestic and imported foods.

With frequent news of outbreaks, which are investigated by the CDC, many people might wonder whether foodborne illness is on the rise – and whether safety measures across the nation adequately protect our food supply.

As of Tuesday, the CDC has investigated 21 multistate foodborne illness outbreaks this year, more than any year in the past decade.

“I think that the issue isn’t that there’s more unsafe food,” Gottlieb said. “I think what’s happening is that we have better technology than ever before to link outbreaks of human illness to a common pathogen.”

In all 50 states, the CDC has the capacity to do genomic testing on samples from infected patients (such as blood samples). It also can genetically link the identified pathogens in human illness to actual food sources.

What is lagging is the ability to do track and trace to a single distributor or grower “because we don’t have as good a technology as we would like in our supply chain,” Gottlieb said.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

Another recent development in protecting the US food supply is the Food Safety Modernization Act, which became law in 2011. Gottlieb said the act represents a “paradigm shift,” as it is based on prevention instead of reaction.

“I think food is more safe now than it’s ever been. We have much more resources and additional tools to do effective surveillance.”