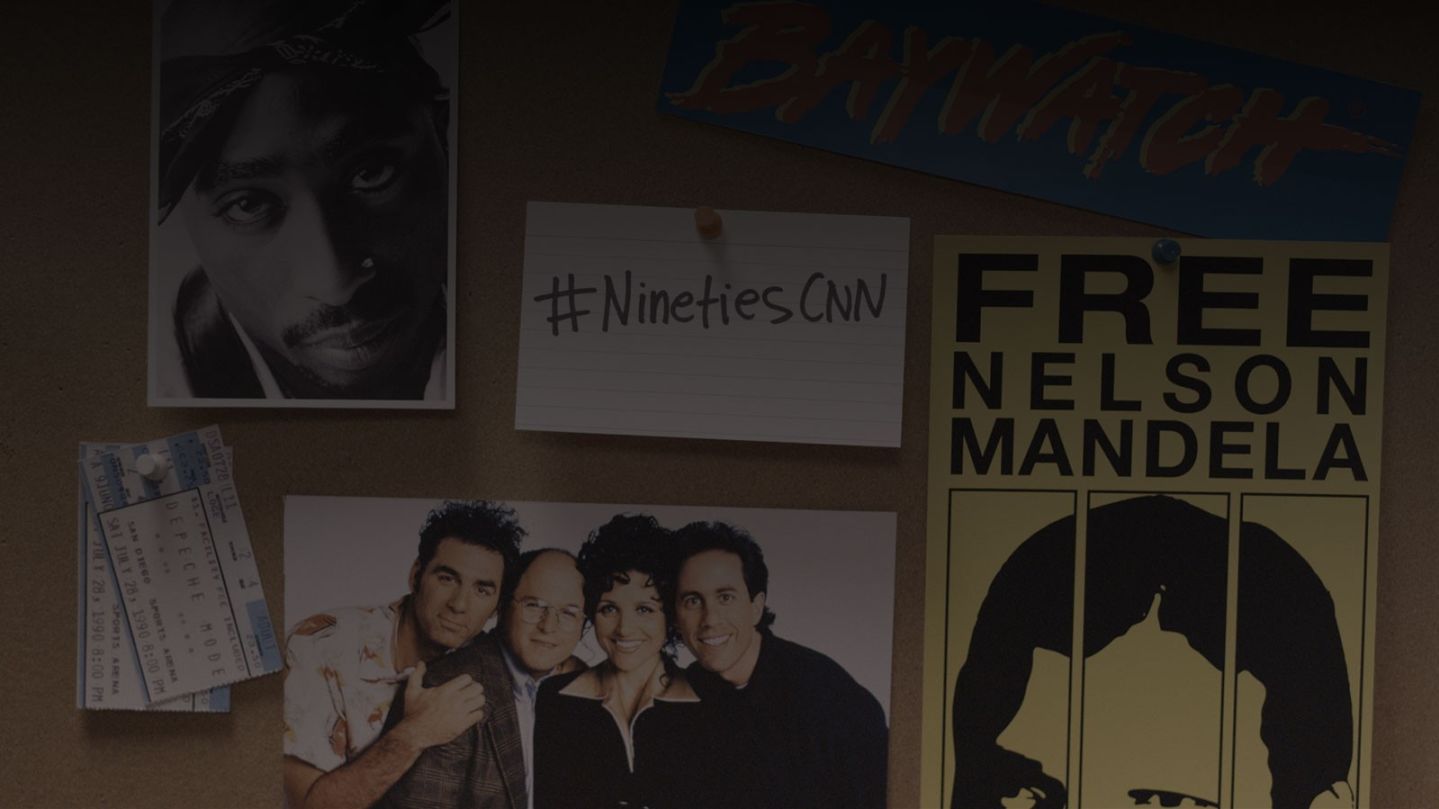

For more on the Rodney King beating and the Los Angeles riots that followed, tune in to CNN Original Series “The Nineties” this Sunday at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

It’s been 25 years since the Los Angeles riots, an event already marked by numerous TV specials, with more to come. Yet one relatively under-covered aspect of the unrest is the role TV and video played – and the jarring realization, played out in multiple cases since, that seeing wasn’t always believing.

The riots that began on April 29, 1992 preceded the ubiquity of cellphone video and the expansion of 24-hour cable news (only CNN existed at the time). In some respects, though, the coverage previewed the age of viral video, which has magnified the sense of injustice surrounding more recent scenarios of young African-American men killed by the police.

A quarter-century ago, the African-American community had long cited abuse faced at the hands of the Los Angeles Police Department, which, under then-chief Daryl Gates, operated like a paramilitary organization.

The advent of video cameras, however, made documenting such excesses more possible. In the riots’ precipitating incident, that was the 1991 beating of motorist Rodney King by what looked to be a group of out-of-control officers, captured by a nearby resident.

“This video camera revolution, finally, they got it,” recalled one community member in the Showtime documentary “Burn Mother—-er Burn!” Smithsonian Channel’s “The Lost Tapes: LA Riots” describes the King beating as “one of the first viral videos.”

Television played those images again and again, raising expectations of guilty verdicts. The community’s anger was further stoked by widely seen surveillance video of 15-year-old Latasha Harlins being shot to death by a store owner, who was convicted but given probation as a sentence.

The officers’ acquittal in the King beating by a predominantly white jury produced “a kind of spontaneous combustion,” as civil rights activist Jesse Jackson said at the time.

Perhaps foremost, though, the shock stemmed from the fact that even confronted by seemingly irrefutable video evidence, African-Americans couldn’t expect protection from the justice system.

“Today, this jury told the world that what we all saw with our own eyes wasn’t a crime,” said then-Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley.

Similarly, the Rev. Cecil Murray called the verdict “a brutalization of truth … whitewashing something that the whole world has witnessed.”

In the years since, the ability to document and distribute perceived police abuses has grown. Not only does practically everyone now walk around with a camera, but many have the ability to disseminate live video – as seen last July, when Diamond Reynolds used Facebook Live to live-stream the aftermath of a Minnesota police officer shooting her boyfriend, Philando Castile.

One recurring argument in response to these caught-on-tape events is that a snippet of video doesn’t always tell the entire story. Those defending the police have seized on details regarding how people behaved in the off-camera build-up to fatal encounters that have often proven persuasive to juries, as well as those inclined to support the police in the court of public opinion.

If there’s a welcome aspect to the glut of made-for-TV Los Angeles Riots anniversary projects, it’s bringing a wider context to what happened.

In “LA 92,” airing Sunday on National Geographic Channel, that includes going back to the Watts Riots in the mid-1960s, and the conditions that persisted after. The same goes for ABC’s “Let it Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992,” getting past the tendency – in the real-time landscape of cable, the web and social media – to zero in on a tragedy and just as quickly move on.

“It wasn’t just one night. It wasn’t just one thing,” “Let it Fall” director John Ridley told ABC Radio. “It was something that built up over time.”

The tools for chronicling such events have become more instantaneous – and thus potentially more volatile. The unsettling corollary of that is the gap between what is seen and believed – filtered through today’s age of media divided into ideological silos – has, seemingly, only grown wider.

“Let it Fall: Los Angeles 1982-1992” and “LA 92” air April 30 at 9 p.m. on ABC and National Geographic Channel, respectively.