Story highlights

Hurricane season began June 1 and ended Monday

Pacific saw above-normal number and intensity of storms; Atlantic activity was below average

Meteorologists say El Nino is the reason for both trends

This year’s hurricane season has officially come to an end, and it was a tale of two oceans. The Atlantic saw another relatively quiet year, while the Pacific, fueled by a strong El Nino, broke a number of records.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration released its final numbers Tuesday, and for the second consecutive season the Atlantic yielded below-normal activity.

In the Atlantic, the season saw 11 named storms, four hurricanes, and two major hurricanes – storms that are Category 3 or higher, and typically the most dangerous.

This fell just short of average, which is 11.5 named storms and 6.1 hurricanes. This was the second year in a row that the Atlantic saw below-normal activity. You’d have to go back over 20 years to find the last time that happened.

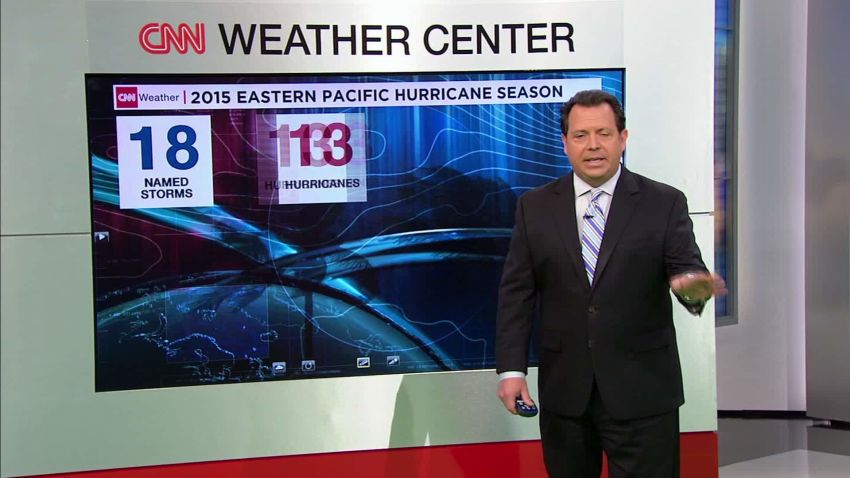

In contrast, the Pacific Ocean hurricane season was well above average, and in fact the eastern and central Pacific shattered previous records.

Record ocean temperatures in the eastern Pacific not only fueled an increase in the number of storms, but also increased the intensity, allowing for a record number of major hurricanes – nine. One of those major hurricanes, Hurricane Patricia, became the strongest hurricane ever to form in the Western Hemisphere, with sustained winds of 200 mph and one of the lowest pressures ever recorded. The central Pacific also shattered its record with 14 named storms, more than tripling the normal number.

El Nino was the biggest factor

NOAA scientists point to El Nino as the leading influence that drove this year’s season, which began on June 1 and ended Monday.

El Nino, which is a pronounced warming along the equator near the coast of South America, has been building to near-record numbers over the summer. This naturally occurring climate cycle changes weather patterns all over the world.

According to Gerry Bell, the lead NOAA hurricane forecaster, “El Nino suppressed the Atlantic season by producing strong wind shear, strong sinking motion, and drier air across the tropical Atlantic. This makes it difficult for storms to form.”

The opposite conditions occur in the Pacific during El Nino years. The record warm water in the Pacific and the low wind shear led to ideal conditions for hurricane formation. “This year was the weakest wind shear on record,” Bell added.

Pacific storm power off the charts

Meteorologists use a measure called Accumulated Cyclone Energy or ACE to measure the potential destructive power of storms. The index takes into account the wind speed, strength and duration. Once again, the Atlantic was well below normal at only 60%. One storm, Hurricane Joaquin, accounted for nearly half the total. Joaquin struck the Bahamas and notably sunk the cargo ship El Faro.

The Pacific ACE numbers, on the other hand, were off the charts. The eastern and central Pacific numbers were more than double the average. The Indian Ocean number was even higher, at nearly triple the average. Two noteworthy cyclones struck Yemen within a week, a remarkable occurrence considering there had been no record of any cyclone with tropical storm or hurricane force winds ever hitting the country.

Meteorologist Ryan Maue posts the ACE numbers, which show that globally the ACE is 140% of normal, meaning that hurricane, typhoon and cyclone activity around the world was well above normal. The Atlantic basin had by far the lowest activity.

Lack of U.S. landfalls

Colorado State University hurricane researcher Phil Klotzbach points out some interesting numbers about the U.S. and its recent lack of hurricanes:

- No major hurricane landfalls in over 10 years. The U.S. had never gone 10 years without a major landfall since records began.

- 10th consecutive year without a hurricane impact in Florida, a record.

- Only 12 total hurricanes in the last three years, the lowest total since the 1992-1994 three-year period.

Will this trend continue next season? It’s too early to tell, but long-term forecasts show the El Nino will likely be finished by next summer and could be replaced by its counterpart, La Nina. Meteorologists and coastal residents will need to watch closely to see how this plays out.