Story highlights

The USA Freedom Act will ultimately end the bulk collection of millions of Americans' phone records

The government will need a targeted warrant to obtain any phone metadata from phone companies

The Senate vote came after a dramatic fight that saw Sen. Rand Paul adored and hated

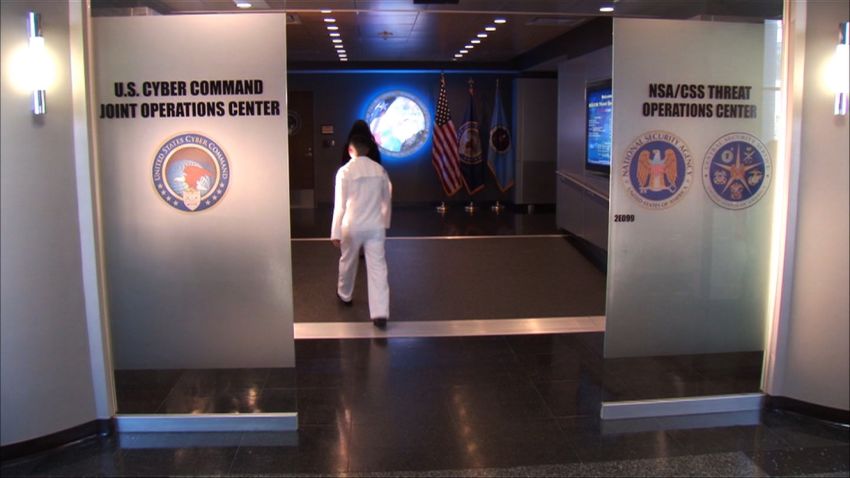

The National Security Agency lost its authority to collect the phone records of millions of Americans, thanks to a new reform measure Congress passed on Tuesday. President Barack Obama signed the bill into law on Tuesday evening.

It is the first piece of legislation to reform post 9/11 surveillance measures.

“It’s historical,” said Sen. Patrick Leahy, D-Vermont, one of the leading architects of the reform efforts. “It’s the first major overhaul of government surveillance in decades.”

The weeks-long buildup to the final vote was full of drama.

Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul assailed the NSA in a 10-hour speech that roused civil libertarians around the country. He opposed both renewing the post 9/11-Patriot Act and the compromise measure – that eventually passed – known as the USA Freedom Act.

Meanwhile, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, and defense hawks such as Sens. John McCain and Lindsey Graham, had hoped to extend the more expansive Patriot Act, arguing it was essential for national security.

RELATED: Are post 9/11 politics shifting?

The Republican infighting broke out during two weeks of debate on Capitol Hill and on the presidential campaign trail. And in part thanks to Paul’s objections, certain counterterrorism provisions of the Patriot Act expired late Sunday amid warnings of national security consequences.

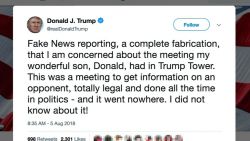

Obama welcomed the bill’s final passage on Tuesday, but took a shot at those who held it up.

“After a needless delay and inexcusable lapse in important national security authorities, my administration will work expeditiously to ensure our national security professionals again have the full set of vital tools they need to continue protecting the country,” he said in a statement.

Now that Obama has signed the bill, his administration will get to work getting the bulk metadata collection program back up and running during a six-month transition period to the new data collection system.

Senior administration officials described a two-step process: The first is the technical process – essentially flipping the switches back and coordinating the databases of information stored by the government – which takes a full day.

RELATED: McConnell refuses to blast Rand Paul

The second is a legal process that could take longer. The government needs to make a filing with the special secretive court – which has authorized the bulk metadata collection program since 2006 – to verify that the metadata programs are legal under the new law.

It’s unclear how long the process would take, but one official estimated the process could take three or four days.

Final passage of the compromise bill was in question until Tuesday, until the Senate successfully rebuffed with three amendments which could have thrown a wrench into the works.

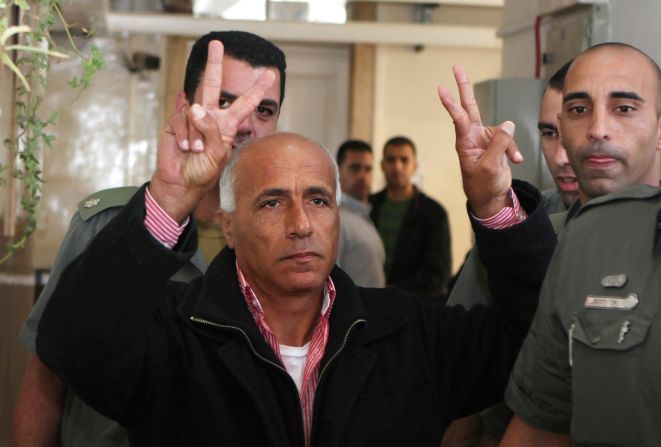

The bill’s passage is the culmination of efforts to reform the NSA that blossomed out of NSA leaker Edward Snowden’s 2013 revelations.

“This is the most important surveillance reform bill since 1978, and its passage is an indication that Americans are no longer willing to give the intelligence agencies a blank check,” said Jameel Jaffer, deputy legal director at the American Civil Liberties Union.

Congress had failed last year to pass a similar reform effort.

The legislation will require the government obtain a targeted warrant to collect phone metadata from telecommunications companies, makes the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (known as the FISA court) which reviews those warrant requests more transparent and reauthorizes Patriot Act provisions that lapsed early Monday.

The bill, though, passed over the strong and impassioned objections of security hawks in the Republican Party and from some former members of the intelligence community.

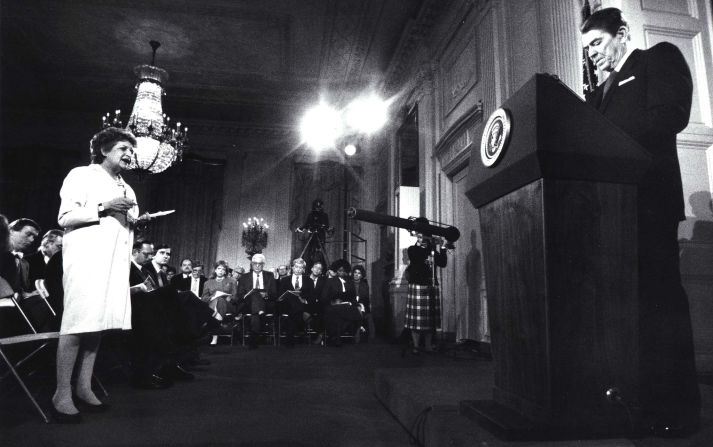

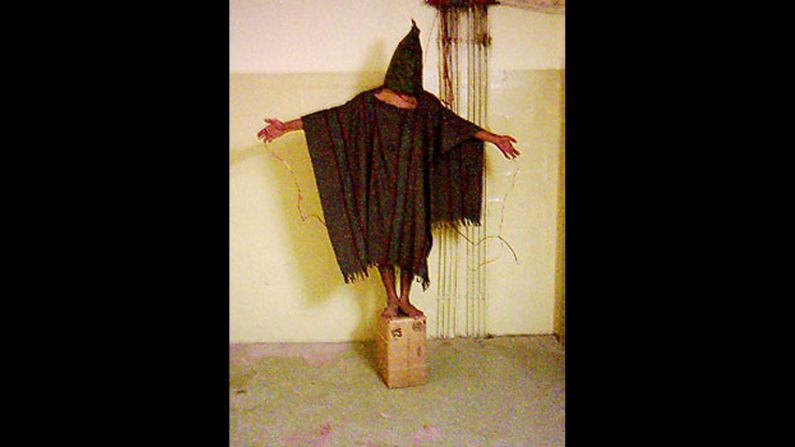

Notable leakers and whistle-blowers

But as the June 1 deadline to renew expiring provisions of the Patriot Act closed in, and as NSA reform advocates refused to budge in the face of charges of damaging national security, top Senate Republicans led by Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell eventually relented, giving way to pressure from House Republicans, the Obama administration and reform advocates in their own body.

McConnell and others realized that the USA Freedom Act, which passed the House three weeks earlier, was their only ticket to keeping counterterrorism provisions like data collection and roving wiretaps alive.

But while McConnell kept up his protest into the final moments leading up to the vote, his fellow Kentucky senator who antagonized his every move to reauthorize provisions of the Patriot Act noticeably avoided the spotlight on Tuesday.

Paul’s weeks of staunch and unflinching opposition to reauthorizing the Patriot Act, and to the USA Freedom Act for not going far enough, ended Thursday with a simple “No” vote on that bill. He even relented in his plan to offer his own amendments to that piece of legislation and didn’t make a prominent speech on the Senate floor on Tuesday.

Paul chalked up his efforts as a win, though, succeeding in leading the bulk metadata collection program to its expiration on Sunday night.

CNN’s Deirdre Walsh, Athena Jones, Ted Barrett, Jim Acosta, Kevin Liptak and Kristen Holmes contributed to this report.