Editor’s Note: Ravi Agrawal is CNN’s New Delhi Bureau chief. Follow him on Twitter: @RaviAgrawalCNN. The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Ravi Agrawal: Indian Prime Minister made progress in certain areas but hasn't yet met the ambitious goals he set

He says many of the expectations will take many years to realize

In politics and life, expectation is everything.

The India I have observed for the past three decades has generally had low expectations. This shouldn’t be surprising: the average Indian makes less than 1/20th what the average Singaporean or American takes home. And Indians have by and large tried to make do – with their own incomes and with the deficiencies of the state.

Businessmen would conjure up loopholes because they were defeated by the system; Indians talked of “frugal innovation” – there’s a single word for it in Hindi, “jugaad” – in part because major Western-style R&D projects were a pipe dream. Dreams were dreamt, but they were modest dreams of a sober Indian middle class life.

Gradually, though, through the 1990s and 2000s, as India began to open up and liberalize, Indians began to get more and expect more. They began to hope – cautiously, of course – that India could be something bigger.

Then came Narendra Modi.

Great expectations

No Indian politician has ever talked so big and so well.

I remember the electrifying 2014 campaign trail. Half of India’s population doesn’t have access to toilets? No problem: we’ll fix that in five years. Communications are difficult? Here’s “Digital India.” Not enough jobs? Here’s the “Make in India” campaign. Think India is dirty? Try the “Clean India” initiative. Global investors scared to put money in India? We’ll make India business-friendly. There was an answer to every problem, a dream for every Indian.

It was a winning formula. Here was a fresh national leader, a bold outsider, saying all the things people yearned to hear. And as a result, Modi won big last May: he was the first Indian Prime Minister in three decades to control a complete majority in the country’s lower house of parliament.

The mood was euphoric. Big business was confident it finally had its man and that this man had a mandate. Middle class India was proud that one of their own had made it. Global investors couldn’t believe their luck: India was finally going to fulfill its potential. By and large, few stopped to ask how; it was difficult not to get swept up by the mood of hope.

Across India, and even around the world, Modi marketed India Inc. He sold the dream.

But with great expectations comes the danger of a great fall.

When marketing backfires

If clothes make the man, they can also break the man. During U.S. President Barack Obama’s high-profile visit in January, Modi made a bold sartorial choice, going with a dark pinstriped suit. It wasn’t just any suit: each pinstripe contained his full name “Narendra Damodardas Modi” in microprint, inscribed hundreds of times across his jacket and trousers.

India wasn’t impressed. The suit cost $16,000, some eight times as much as the average annual salary in India. (In the face of criticism, Modi later had the suit auctioned for nearly $700,000, with the proceeds going toward a project to clean up the River Ganges.)

Later, in May, at a speech delivered to Shanghai’s Indian community, Modi said this to his audience: “Earlier, you felt ashamed of being born Indian, now you feel proud to represent the country.”

The remark was Modi’s way of marketing his year in power, but it drew an instant backlash on Indian TV. Many Indians said Modi was mistaken in assuming they had ever been ashamed. #ModiInsultsIndia began to trend on Twitter.

Modi’s relentless marketing worked when he was a candidate, but it is tougher to pull off as an incumbent.

The aura of invincibility that Modi carried a year ago has been punctured. In February, despite hitting the campaign trail himself, Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party suffered an embarrassing defeat in Delhi state elections, picking up just 3 out of 70 seats available.

Meanwhile, the stock markets are beginning to sour. Reality is setting in: India was always going to be a chaotic, messy democracy.

But opinions can seesaw. It’s worth taking a step back to look at Modi’s first year in office: How well has he really done?

It’s the economy, stupid

The most important indicator by which to judge Modi is the economy. And the Indian economy is growing well.

There is no doubt that Modi has been lucky.

When he assumed office a year back, global crude prices were running at about $100 a barrel. By the start of the year, they had plummeted to $50 a barrel. For India, which imports about 80% of its crude, the fall in global prices was an immense windfall. For a start, the deficit has stayed under control.

Second, inflation has been kept in check.

Third – and Modi deserves a lot of credit for this – the government has taken the opportunity to cut long-running subsidies on diesel while pushing up fuel taxes. This might cause trouble on the streets when oil prices go back up, but it was a brave and important reform to put in place.

Beyond oil prices, the rupee remained stable, among the strongest performers in the emerging markets. Stock prices soared some 30% in 2014 before pairing gains this year, but they are still up 16% for Modi’s year in power. The larger economy has continued to chug along at more than 7% a year, making India the fastest-growing big economy in the world.

So far, so good.

Critics say some of the above could have happened on autopilot. Where are the “big-bang” reforms Modi promised? Where are the big changes? After all, two of his main reform bills – a national Goods and Services Tax, and a Land Acquisition Bill – are actually older ideas first mooted by the Congress Party, now in the opposition. Both plans are mired in political gridlock but still expected to pass in some form this year. When they do, even watered down, they will be important steps forward for the economy.

The Indian columnist Mihir Sharma argues that by not pushing through major infrastructure projects and changes, by not living up to the immense hype, Modi has wasted his rare parliamentary majority, what he describes as “a once-in-a-lifetime wind at his back.”

“We misdiagnosed the slowdown under the last government,” writes Sharma. “It was not a problem of ‘paralysis’ at the top, to be solved by a ‘strong leader’… In fact, India was faced with a systemic problem, born of the wrong laws and insufficient regulatory capacity.”

But systemic problems take much longer than 365 days to fix. When you examine the reasons why doing business in India is so difficult: tax uncertainty, dozens of permits to start a business, daily corruption, broken infrastructure, shortage of trained talent, it is clear that none are easy-fix ones. Perhaps Modi shouldn’t have made them seem so.

There are larger problems in India that will take decades to tackle: education, health care, pensions, pollution. In starting a big financial inclusion program for the poor – some 150 million bank accounts have been opened, mostly in rural India – Modi has the makings of something big. With this program, he could cut subsidies and institute direct cash transfers, while also creating a rudimentary pension and insurance scheme.

But Modi’s detractors say his plans are too incremental – he could have done more with an absolute majority, they say. At the very least, he promised more than he could deliver.

One of the platforms Modi ran on was to rid India of corruption. “I won’t take, and I won’t let anyone take either,” he would often say in his speeches. On that front, at least, one can say India hasn’t unearthed any of the megascams seen under previous governments. But it will be crucial for Modi to be able to maintain that claim moving forward.

Domestic worries

Right from when Modi was first mooted as a national political figure, India watchers have had reservations about Modi’s commitment to religious diversity.

On this front, while there has been no major discord, Modi has spurned a great chance to completely refute his critics.

After months of reports of forced religious conversions – ostensibly carried out by Hindu groups emboldened by Modi’s electoral victory – and violent attacks on churches across India, the Prime Minister remained worryingly silent. It took a rebuke from Obama for Modi to finally address these reports, strongly reaffirming freedom of faith in India.

It is also worrying that India has placed the Ford Foundation, a major U.S.-based charitable organization, on a national security watch list, essentially preventing it from funding interests in India without permission from the government. The reason why is well-known in India: the foundation has funded an Indian group that held workshops on religious violence, including the 2002 Hindu-Muslim riots that took place in Gujarat, the state Modi ran at the time.

The government has described groups such as the Ford Foundation as “agents of Western strategic interests.” Some 9,000 NGOs have had their registrations canceled; the environmental group Greenpeace is on the verge of closure in India.

Not only are these moves dangerous for democracy in India, they are also ill-advised in a political and economic sense. Can Modi afford to erode the priceless view that India is the world’s biggest truly free country?

Simply put, he cannot.

Foreign policy

Few expected Modi to be a strong foreign policy leader; after all, he was a newcomer to national and international politics. Yet Modi has been a revelation on the world stage, a complete natural.

Ever since the days of the Non-Aligned Movement, co-founded by India’s first Prime Minister, New Delhi has been seen as punching below its weight on global affairs. One-sixth of humanity felt inadequately represented. Modi is beginning to change that perception.

Right from the start, when he scored a coup in inviting South Asian leaders, including Pakistan’s Prime Minister, to his inauguration, Modi has displayed a decisive and deft touch.

Unlike with domestic affairs, the PR game has helped Modi on foreign affairs. He has successfully projected himself as being close to Obama, who became the first American chief guest at India’s Republic Day parade, and has simultaneously cultivated a close understanding with the likes of Japan’s Shinzo Abe, China’s Xi Jinping and Russia’s Vladimir Putin. The point to all of this, of course, is to grow trade and opportunities. Modi has undoubtedly opened doors to India. He has won over the increasingly significant Indian diaspora. This will have economic and social benefits down the road.

Under Modi, India remains relatively nonaligned. But more importantly, India seems to have moved beyond being defined by Pakistan or South Asia: it has more of a global feel to it, projecting power and ambition.

The next 365 days

In the end, Modi will be judged by India’s people on whether they feel their lives are improving, and here the Prime Minister has some breathing room. India is going to keep growing for many years, in part because it is starting from a low base and is blessed with hundreds of millions of young people hungry for jobs and opportunities.

But those very same job-seekers could turn out to be Modi’s undoing. Unlike previous generations of Indians, they expect more. And for that, Modi can probably blame his own PR campaign.

The reality is that delivery takes time, especially in India. Modi has made his task harder by overselling his ability to deliver. If global oil prices go up again, Modi’s task will get even more challenging.

There is much to do. Modi’s mantra for the next 365 days should be less PR and more action, especially at home. He still has the tools and the confidence of the people to be India’s most transformative leader in history.

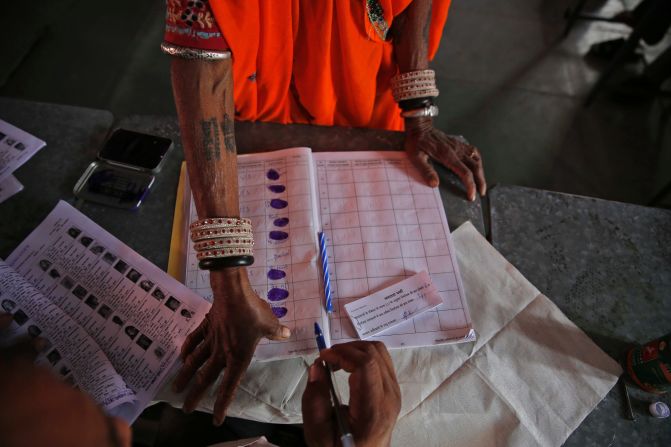

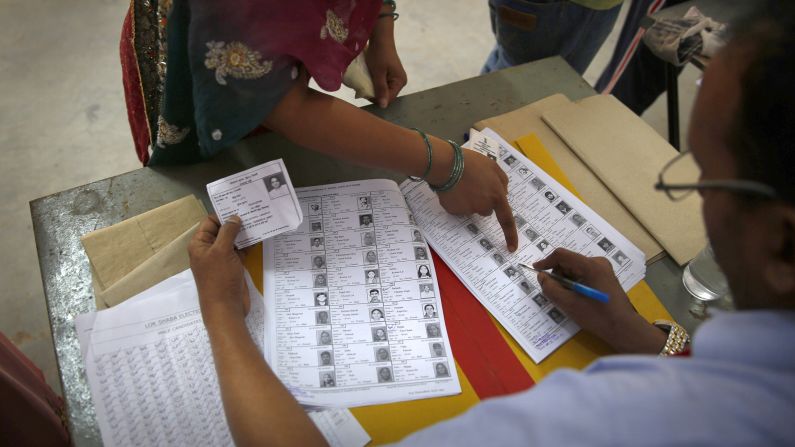

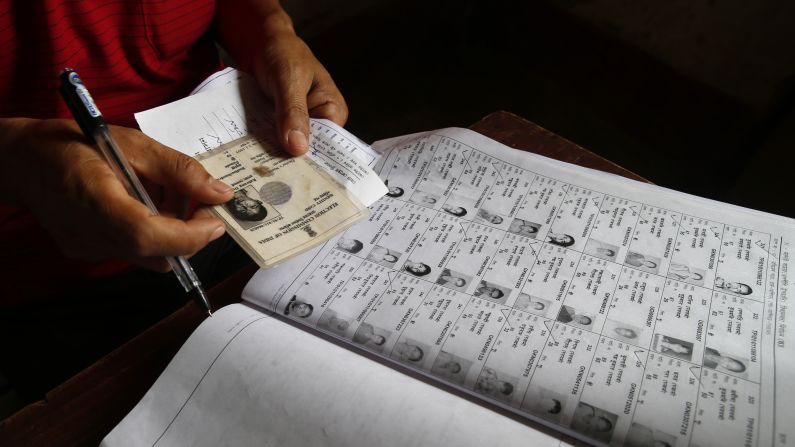

India's election: The largest in history

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.