Story highlights

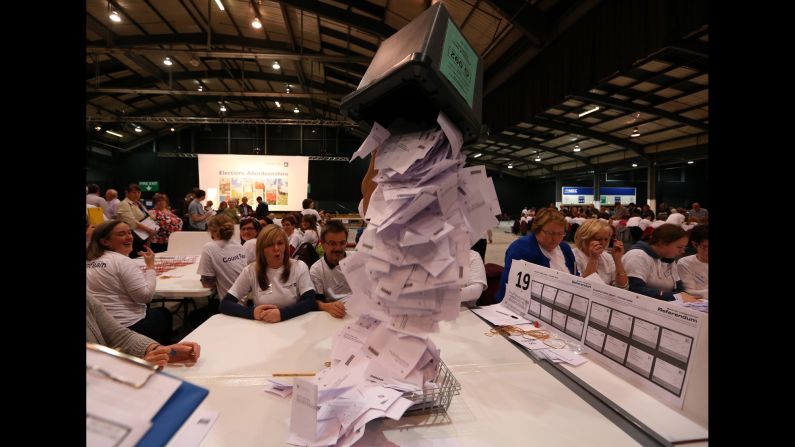

Scotland goes to the polls Thursday to vote: "Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?"

The country is not alone: From Belgium to China, separatists are looking to break away

Separatists across the world will be looking closely at Scotland's referendum and its result

97% of eligible Scots have registered to vote -- an unprecedented amount of engagement

“Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent country?”

This is the question the people of Scotland will be asked today as the country holds a referendum that could see an independent Scotland by 2016.

Engagement in Scotland is at record levels, with 97% of eligible Scots registered to vote.

But Scotland is not alone when it comes to seceding from larger political entities – across the globe, independence movements agitate for separation. So what will the Scottish outcome – either “Yes” or “No” to that all-important question – mean for these independence hopefuls?

QUEBEC

In 1995 Quebec held its second referendum in 15 years on a split from Canada, and while the 1980 vote had seen Quebecers reject sovereignty by a conclusive 58.2% to 41.8%, the later ballot was an altogether tighter race.

More than 93% of the province’s registered voters turned out to have their say at the end of a sometimes bitter campaign, which ended with the separatist Parti Quebecois defeated by an agonizingly narrow margin of just over 1%, 50.6% to 49.4%.

Some blamed the clunky and confusingly-worded question for the loss. While Scots will this week be asked simply: “Should Scotland be an independent country?” back in 1995, voters in Quebec faced an altogether more challenging proposal:

“Do you agree that Quebec should become sovereign, after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new Economic and Political Partnership, within the scope of the Bill respecting the future of Quebec and of the agreements signed on June 12, 1995?”

After the 1980 poll, Premier Rene Levesque conceded bullishly with the words: “until next time!” but since the 1995 vote Quebec’s appetite for independence appears to have shrunk: support for both the regional Parti Quebecois and the national Bloc Quebecois has waned.

But the Quebecers’ distinctive identity is still going strong: festivals celebrate the province’s history, blue-and-white fleur-de-lis flags fly over its towns and cities, and French is widely spoken.

In 2006, Canada’s parliament voted to recognize Quebec as “a nation within a united Canada,” and for the moment, at least, it seems Quebecers are happy with that.

CATALONIA

For the third year running, hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets of Barcelona on September 11, Catalan national day, demanding a vote on independence be held.

They and some of their political leaders want to hold a referendum on November 9, which the Spanish government staunchly opposes, and says is unconstitutional.

Madrid argues that Catalonia, which represents one fifth of Spain’s economy, already has broad home-rule powers, including its own parliament, police force and control over education and health. And it insists that the Spanish Constitution does not allow any of Spain’s 17 regions to unilaterally break away.

Last week, one of Catalonia’s key political figures, Oriel Junqueras, leader of the Esquerra Republicana – or Republican Left – party, said if the government in Madrid were to block citizens’ exercising their “fundamental right” to vote, there could be a need for civil disobedience.

Those in the crowd Barcelona earlier this month said that if Madrid blocked the referendum, people should still deposit their ballots.

“Many of the people we spoke to in the street have drawn immediate parallels to the Scottish referendum saying, ‘the British government has agreed to let Scotland vote – why isn’t Spain letting Catalans vote?’,” CNN’s Al Goodman, who covered the protests, said.

A referendum is expected to ask a two-part question: “Should Catalonia be a state?” And those who vote yes to that can then go to vote on the second question: “Should that state be independent?”

Goodman says polls indicate that a majority of Catalans want to have a chance to vote but that less than a majority would vote for independence, given the chance.

But despite numbering in the hundreds of thousands, those calling for independence in Barcelona last week did not represent all the region’s 7.5 million people.

A smaller gathering of several thousand took to the streets the same day in Catalonia’s second largest city, Tarragona, calling for the region to remain a part of Spain.

One of those protesters told CNN: “The reason we want to remain a part of Spain, is because we are a part of Spain.”

BELGIUM

As a country with famously diverse provinces, and given its proximity, both geographically and culturally to Scotland, it could be seen that the Scottish vote this week would be an important test-bed for independence movements in the European nation.

But not necessarily, said Regis Dandoy, a political scientist and associate researcher at the University of Brussels (ULB) and the University of Louvain (UCL).

First off, Belgium has some bad experiences with referendums. In 1950, one pushed the country almost “to the brink of civil war” over the question of whether the king, who was accused of having Nazi sympathies, would be allowed to return from self-imposed exile in Switzerland.

And despite the much-publicized differences between the Belgian provinces, Dandoy says that within Flanders, the region most cited to break away, support for full independence hovers only at around 12-15%.

“Devolved powers over time are the reason why independence is not yet an issue in Flanders,” he said. “We’ve had six state reforms since 1970 and in each of these we’ve given more power to the region. Nowadays Flanders is one of the most autonomous regions in Europe.

“As soon as the Flemish nationalist party becomes strong, well, then you have a reform that gives more autonomy.”

It is a tactic that is being employed by the Unionists in Scotland – as polls narrow, the UK’s main political parties have all pledged further devolved powers to the Scottish parliament in an effort to head off the threat of secession.

And what of EU membership, an issue so close to so many Belgian hearts? Dandoy says that, despite the efforts of some parts of the media and the “No” campaign concerning Scotland’s EU membership, Dandoy said the threat of Scotland’s ejection from the body is a “fake argument.”

“This is not an argument, this is what has been used by the people who want ‘No’ to win. There would be no problem for Scotland, Flanders, Catalonia to join the EU because they are democratic states, they respect all the rules, so there would probably not even be a process of application to the EU.”

Scotland, Dandoy said, “should not be afraid of independence.”

CHINA

China has reason to be wary of secessionist movements, with voices from Tibet to Hong Kong – not to mention the “renegade province” of Taiwan – championing independence from Beijing.

With this in mind, the state-controlled Global Times recently took a scathing line on Scottish independence, stating that “if Scotland gains independence, the UK will descend from a first-class country to a second-rate one, which will once again break the balance within Europe. And its consequence may even wield influence upon international geopolitics.”

The restive western province of Xinjiang, home to a sizable population of ethnic Uyghurs, has one of the most vocal independence movements.

Uyghurs accused of being separatists by the government have been making headlines lately amid a spate of violent incidents. Attacks in railway stations and other public places in the province and further afield have prompted Chinese authorities to launch a massive anti-terrorism campaign in Xinjiang, which ethnic Uyghur activists call East Turkestan.

Rebiya Kadeer, the president of the World Uyghur Congress told CNN that her cause does not even have the “rudimentary elements” of a road map to self-determination.

“We’d certainly like to see the implementation of the same model (as the Scottish referendum) in our homeland … if there are parties in the British parliament that openly campaign for independence, this is something that is unimaginable in East Turkestan,” she said, via a translator. “The day we raise our voice, the day we raise our concerns, we are killed.

“Freedom and to be free independent is the god-given right of every individual, every nation and people. Nothing is more precious that independence and liberty. Freedom and independence is the greatest happiness. From this point of view, I support the decision of the people of Scotland to conduct a referendum to determine their political future.”

KURDISTAN

The Kurdish people have long agitated for a homeland of their own, and paradoxically, it is now, when a united front is needed against ISIS, that the Kurds have their best chance of at least gaining significantly more autonomy in Northern Iraq.

After disbanding the government in Baghdad in the face of the looming crisis, lawmakers in July appointed Fouad Massoum, a highly-regarded Kurdish politician, to the role of president.

The Kurds have been divided and repressed since the end of the Ottoman empire, when the current international borders of the region were largely devised leaving Kurdistan, as proponents like to say, as the largest stateless nation in the world.

Kurds have suffered at the hands of Iraq’s former dictator Saddam Hussein’s regime, as well as by successive governments in Syria, Turkey and Iran and have endured much in their quest for their own state.

As a result, many from the ethnic group wish to see their own homeland, independent from the countries that split up their heartland at the beginning of the 20th century. Iraq wishes to maintain the integrity of the country – any split could also see the southern Shiites agitate for a greater degree of independence, and the autonomous region provides a buffer from ISIS incursions.

Like Scotland, Kurdistan is rich in oil, another reason Iraq would be loath to countenance a split.

Syria and Turkey, too, have sizable Kurdish populations and would be loathe to see any move to give Iraqi Kurds greater independence.

Indeed, the idea of a split for Turkey’s southern population is so far from a reality that an editorial on Turkey’s Cihan news agency stated: “We don’t even need to discuss the willingness of Ankara to recognize the outcome of a unilateral effort by the Kurds in southeastern Turkey to gain independence through a referendum.”

Kurdish fighters have had some success in repelling ISIS and regaining footholds in previously-held extremist territories. It remains to be seen what value the new Iraqi government places on their defensive capabilities, and what leverage the Kurdish government can gain for their assistance in repelling ISIS forces.

Scottish teens face historic vote

CNN’s Al Goodman contributed to this report