Story highlights

British-born Abdul Waheed Majeed carried out a suicide bomb attack on Aleppo prison

His mother misses him and his elder brother says "his intentions were bona fide"

The soon-to-be bomber had sent his family pictures of him hard at work in tent camps

According to his brother, Majeed never made a farewell phone call to his family

Abdul Waheed Majeed first hit the headlines in 1982. A faded clipping from his hometown newspaper in Crawley, just outside London, carried a photo of the then 10-year-old clutching his pet cat “Billy.” The full-page report, titled “Cat On A Hot Roof” told how young Majeed raced into the burning wreckage of his mother’s corner store and rescued his furry friend.

Three decades later – in February – Majeed’s story hit the media again. The headline this time: “Video of British suicide bomber released.”

The reports came just after al Qaeda-linked jihadis in Syria posted an online video showing a suicide attack on the notorious Aleppo prison. President Bashar al-Assad’s brutal regime was reportedly torturing hundreds of prisoners there. The recording showed Majeed, who made his living in Britain driving a highway maintenance truck, crashing into the prison gates at the wheel of a Mad Max-style dump truck. Thick steel plates had been welded to the cab of the vehicle for protection against enemy gunfire.

“I miss my son so much. He was a good boy,” his mother Maqbool Majeed whispered to me during our conversation at her home in Crawley, about an hour’s drive from central London. She said she came with her husband from Pakistan to Britain almost 60 years ago. Her two sons and a daughter were born and raised in England. Photos from the family album show the Majeed children had what appeared to be a fairly normal British childhood. When Majeed reached adulthood he married and is survived by his wife and three teenage children.

Majeed’s elder brother Hafeez has rarely spoken publicly since the suicide bombing. But he made clear that’s not out of shame. “We feel no shame whatsoever,” he said. “Whatever [my brother Abdul] Waheed did, his intentions were bona fide and true to the heart. His whole purpose was to save people in that prison who had been tortured and raped.”

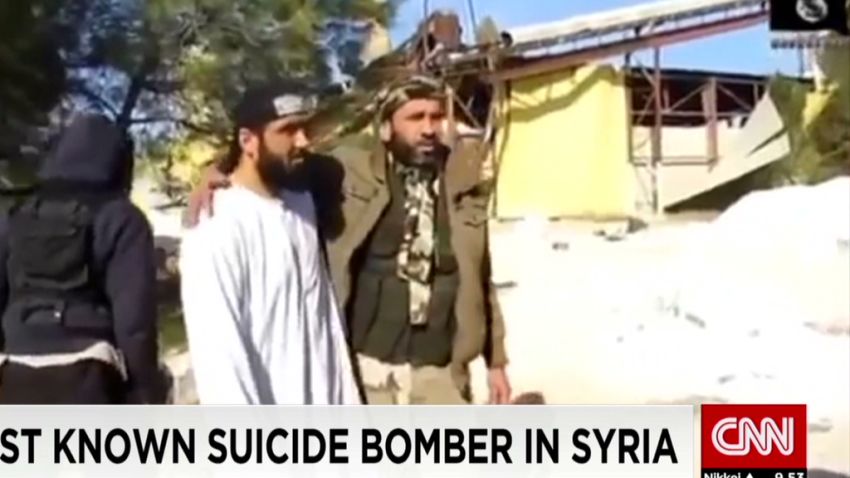

In the video depicting his final moments, Majeed appears calm as camouflage-clad Chechen jihadis wrap their arms around his shoulders. Syrian rebel sources say that unit had recently defected from ISIS to the al Qaeda-affiliated al Nusra Front. His childhood friend Raheed Mahmood, who traveled to Syria with him, said Majeed appeared composed.

“He was obviously at peace,” Mahmood told me. “The idea wasn’t troubling him in any way. I can only put that down to faith and the idea he knew where he was going.”

An electrician and plumber by trade, Mahmood returned to Crawley about a month before Majeed blew himself to smithereens in that attack at the start of February. Mahmood and Majeed volunteered as drivers on an aid convoy operated by a group of British-based Muslim charities in late July 2013. A handful of Muslim NGOs are currently being investigated by UK authorities on suspicion they may have been funnelling British fighters to extremist groups in Syria or may have violated fund-raising rules by donating cash to radical groups.

“There was lot of talk of convoys going down there and taking aid, “Mahmood said. “Abdul Waheed just raised the issue and asked me how I felt, so I turned round and said let’s do it.” Once in northern Syria, not far from the Turkish border, the pair volunteered to stay on, helping civilians in refugee camps. Majeed’s truck driving skills were in high demand. He also knew how to operate diggers and helped build new camps and lay drainage pipes.

Mahmood described the myriad Syrian rebel groups as a “people’s resistance force” and said most people in the refugee camps had relatives fighting against the Assad regime. They frequently saw gun-trucks and heavily armed rebels driving through. They regularly saw fighters from all the factions, including ISIS and al Nusra, in the camps, sometimes bringing supplies to stranded civilians.

“ISIS would come and help as would the other groups,” he said. “You’d hear about people swapping from group to group unsure of whom to fight with. Young people would be promoting their group. It didn’t really seem to matter too much whom you were fighting for.”

But Mahmood said he had no idea his friend Majeed had been recruited. The soon-to-be bomber had sent his family plenty of pictures showing him hard at work in tent camps. Many of the snaps showed him surrounded by children. In one, he was even wearing flashing “Minnie Mouse” ears in an apparent effort to brighten up daily life for youngsters around him.

According to his brother, Majeed never made a farewell phone call to his family. The last time he phoned in January, his family assumed it was just a routine weekly catch-up. “In retrospect I should perhaps have paid more attention to that phone conversation,” his brother Hafeez told me. “He said he loved us all very much. He said I know you’re looking after the family and if I’ve done any wrongs I hope you can forgive me.”

He never phoned again.

Behind him in the small family garden, filled with summer flowers, his mother shed silent tears. “I don’t know what happened. I just don’t know. Only God knows,” she said. Neither family nor friends say they had any inkling Majeed was planning to blow himself up. There were contradictory reports about how successful the attack was. Some accounts suggested more than 300 prisoners had been freed. Other reports claimed Majeed detonated the truck short of its intended target.

His brother, though, describes the infamous Assad-regime prison as a “legitimate military target.”

“If he had been a British soldier and carried out that brave act of heroism, he would have been awarded the posthumous Victoria Cross,” he said, referring to the British military’s highest honor for valor.

Unsurprisingly, the British government did not agree. UK intelligence services estimate that more than 500 British nationals may be fighting with ISIS or other jihadi groups in Syria or Iraq. And British Prime Minister David Cameron has announced new measures to crack down on Islamic extremism and block Britons returning from conflict zones in the Middle East.

“Our family didn’t have time to grieve. As soon as we took a breath the police were knocking on our door to carry out searches under the Prevention of Terrorism Act,” Hafeez Majeed said. Since his death, police and media investigations have revealed Majeed’s alleged links to radical Islamists in Britain.

In an interview with a London newspaper, Syrian-born imam Omar Bakri Mohammad claimed Majeed had been his driver on an unspecified number of visits to Crawley between 1996 and 2004. The UK government excluded Bakri from Britain in 2005, accusing him of being a hate preacher. The same newspaper report alleged Majeed had been friends with two Muslim men – also from Crawley – convicted in 2007 of plotting to bomb a London nightclub. Hafeez Majeed explained his brother had chauffeured Bakri on a “few” occasions but did not share his radical interpretation of Islam. “He wasn’t as, press speculation says, a jihadist, a man born to fight. He had no instances of violence at all in the UK. He was not a threat to the British public,” Hafeez Majeed said.

Majeed does not fit the profile, being promoted by the government, of a Muslim misfit living a deprived existence, easy prey for radical Islamist preachers or online recruiters. His brother says it was perhaps the sight of civilians suffering in the war in Syria or horror stories of the Assad regime’s action that may have pushed Majeed to become a suicide bomber.

But he’s sure that, if he had realized in time, he would have tried to halt his brother’s mission. “If I had known I would have told him please don’t do it,” Hafeez Majeed said. “Please, please, please. You’re much better off being alive so you can help all those people.”

READ: Opinion: Muslims: We’re not all extremists