Story highlights

Kristan Bromley targets Olympic glory in final ever competition in Sochi in 2014

Bromley designs the sleds that he and girlfriend Shelley Rudman race

He switched from design work on the Eurofighter with BAE to this on a whim

Briton is a past World, European and British champion now targeting Olympic glory

It is akin to Sebastian Vettel designing his own Formula One car, getting in the cockpit and driving it to the world title.

In F1, it would be a mission impossible; in the winter sport of skeleton racing it is, at the very least, a monstrous mission improbable which Briton Kristan Bromley has made an infinite reality from the unlikeliest of beginnings.

It has earned him the nickname Doctor Ice and brought him world, European and British titles.

The one medal missing from the trophy cabinet is an Olympic one, achieved by his fiancee and mother of the couple’s daughter, Ella, Shelley Rudman, who won silver seven years ago in Turin on one of the sleds he designed.

There is a somewhat laughable nature to how he found a new career path in such cutting-edge design while based at BAE Systems and tasked with working on the Eurofighter Typhoon, which made its combat debut in Libya in 2011 with the Royal Air Force and Italian Air Force.

“I got a memo sent round internally inviting me to a talk about Bob Skeleton,” he recalls. “I’d never heard of the sport so I asked one of the guys, ‘who is Bob Skeleton?’ – I thought it was a guy to start with.

“You can imagine my surprise that it turned out to be a sport that changed my life completely.”

It is a leap of faith to go from the Eurofighter, which cost an approximate £200m each, to design what is effectively a steel tray designed to ensure an athlete is propelled at speeds of up to 130km/h down a sheet ice bobsled run – head first.

“I just got hooked on the sport,” he admits. “I’d finished at university and was back at British Aerospace (now BAE Systems) and we were approached by the British skeleton team to help with their performance.

“At the time, they were at the back of the field using second-hand equipment from whoever they could.

“I was one of the British graduates starting and, three months later, I was the only one working on it, and I got Nottingham University to sponsor it.”

Sink or swim

It spawned his PhD on “factors affecting the performance of skeleton bobsleds” but it was never with a view to competing himself, which came about by force rather than forethought on his part.

“I first went to Altenberg in Germany with something put together with a few nuts and bolts and none of the British team would ride it,” he recalls.

“There was this rule, you had to prove it first. So it was a simple decision that I could either sink or swim.”

He swam or at least crashed, got on again, got hooked and could not stop.

Two years later, he was competing properly and after just a year of competition he was British No.1.

Fittingly, he won his first major crown – the European Championships – at the same Altenberg venue in 2004 before winning the world title four years later at the same venue, one that has in many ways defined him.

If he was a designer first and a competitor second, the two now run in parallel.

For the early years of his career, he used BAE as his base to create the skeleton before launching Bromley Technologies with his brother Richard in 2000.

Working together, Bromley the competitor designs the sleds, brother Richard manufactures them.

For Bromley, the older of the two siblings, his engineering began – with an admittedly Winter Olympic slant – when he nailed a pair of his Wellington boots to two planks of wood to create his own DIY skis in his father’s workshop as a five-year-old.

“I always liked making things but particularly making things go fast, so this was an inevitable end in some ways.”

The process has become increasingly technical in the intervening years but he still insists the approach can be simplistic at its core.

“You break it down as having to go from point A to point B, and you have a certain amount of energy,” he explains, “some of which gets lost along the way. My work is to make sure it is more efficient and goes faster. I design it, and I’m the test pilot too.”

Drawing board

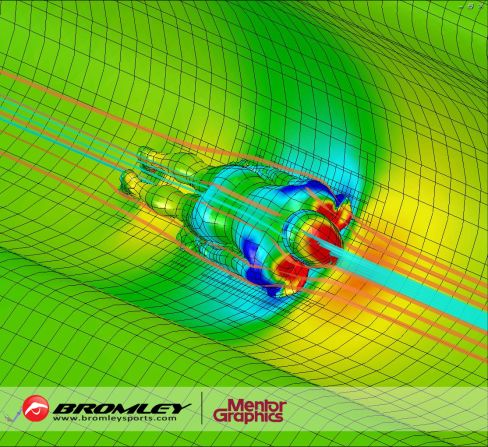

Despite his engineering background he had no experience in computer-aided design nor computational fluid dynamics, a branch of fluid mechanics that uses numerical methods to solve and analyze issues concerning fluid flows, but, with the help of sponsors, he sat himself down and taught himself.

“I’ve always been of the view that yes there are hurdles but there are ways around them,” he adds, “and it’s a never-ending task because you can always go faster.

The key is understanding, if you understand the problems, you can go faster.”

Bromley explains that he has virtually gone back to the drawing board to create a sled capable of winning him that, as yet, elusive Olympic title in the last two years.

What that is exactly, he is loathe to go into detail at the risk of alerting his rivals to what he sees could be a potential advantage but he also argues it is not just about the sled.

“I want to give myself and Shelley the best possible chance but the sled doesn’t win, the athlete does,” he says, looking forward to the Winter Olympics in Sochi early next year.

“For example, at BAE I had the most cutting-edge materials. I based the sled on the air duct of the Eurofighter using carbon fibre, but it didn’t necessarily make the sled go faster.”

The current sled has a steel chassis for its base, able to deal with the top speeds that will be hit in Sochi, the four or five Gs going through it, with Bromley on board akin to half a tonne at full pelt on the ice.

“But again it’s all about understanding,” he says. “If you understand something, it’s easy to change it.

“We’re always trying to understand the dynamics of the sled and the aerodynamics of the athlete. We also need to personalise the aero as what works for me won’t necessarily work for Shelley.”

High-octane world

For Bromley, there are three key areas to his design approach: the aerodynamics, the runners on the ice with its control and handling, and the influence of the sled with its feel on the ice.

To focus on that aero work in particular, he has sought the help of all and sundry, including the use of the wind tunnels of two F1 teams.

Much like F1, mastering the tweaks and additions that work and don’t work can prove to be a very fine art.

“I’d say that 19 out of 20 times, you do stuff that doesn’t work,” he admits. “You have theories, isolate one thing but then it has an impact on everything else.

“It can work in some ways and have a negative effect in others. But you do get that Eureka moment when it clicks. I think I’ve had that about seven times in my career and that’s certainly helped me to win major championships.”

As for Bromley the athlete, he is, by his own admission, an adrenalin junkie, his earlier love for motocross replaced by the similarly high-octane world of skeleton racing.

In the past, he used to be an aggressive competitor in terms of his approach to a course, now he is more technical, more free-flowing, enabling him to let the sled do more of the work.

So how will he do at Sochi and will the course suit him? “I hope so but a bit like an F1 driver, everyone has a favourite course and mine’s always been Lillehammer, it’s where I still hold the course record.”

At 41, he is an older competitor although athletes have tended to win medals in the event in their late thirties and early forties. He still believes he is at his peak and for the first time in five seasons approaches the season start without an injury setback.

His training is akin to that of a sprinter, explosive work in the gym, on the track and on the ice, although because of the nature of the sport, his sprinting is limited to 30-metre bursts at the very maximum.

‘Doctor Ice’

With age, the only major change has been allowing more recovery time and understanding his ageing limbs better.

The Olympics will be his last ever outing as a competitor, his focus after that solely on his future business and the aim is to get through this last season in one piece.

To date, the worst injury he has sustained crashing is a broken hand but the death of Nodar Kumaritashvili in the men’s luge at the same course as the skeleton at the last Winter Olympics highlights the inherent dangers of the sport.

“There are risks at that speeds but the courses are designed for the sled to take the hit,” said Bromley.

“It’s about 30 or 40kg so you make sure it’s in front of you, then you just slide on. There’s ice burns but that’s usually the worst of it. But such is the design, you won’t hit the ice head on, usually on the side.”

“Doctor Ice,” so named by an English newspaper after he travelled back from Salt Lake City with a bobsled full of 20 gallons of water to freeze and better understand as part of his PhD, will use brain and body will do their utmost to sort out the one caveat from his career CV.

“Anything can happen once you’re at the Games but a medal’s realistic,” he says.

Science and skill will hold the key in what, come next year, will have been two decades dedicated to the discipline.