Editor’s Note: Megan Bradley is a fellow in Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution, where she works with the Brookings-LSE Project on Internal Displacement. Her work addresses the rights and well-being of internally displaced persons and refugees. Her research also examines issues of transitional justice and accountability for human rights violations. She is the author of Refugee Repatriation: Justice, Responsibility and Redress (Cambridge University Press, 2013).

Story highlights

Megan Bradley met traumatized, fearful Syrian refugees at a camp and hospital in Jordan

She says neighbor countries' hugely generous to shelter them; global community must help

She says it's crucial to keep borders open for fleeing Syrians and to keep kids in school

Bradely: Helping displaced still in Syria very hard; opposition needs help to provide social aid

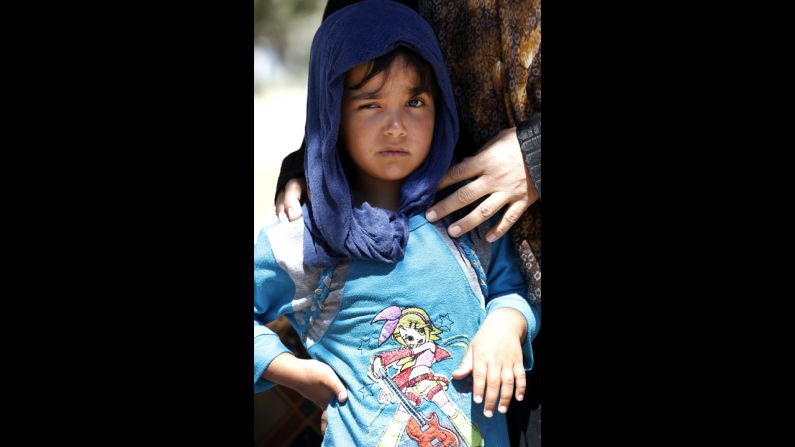

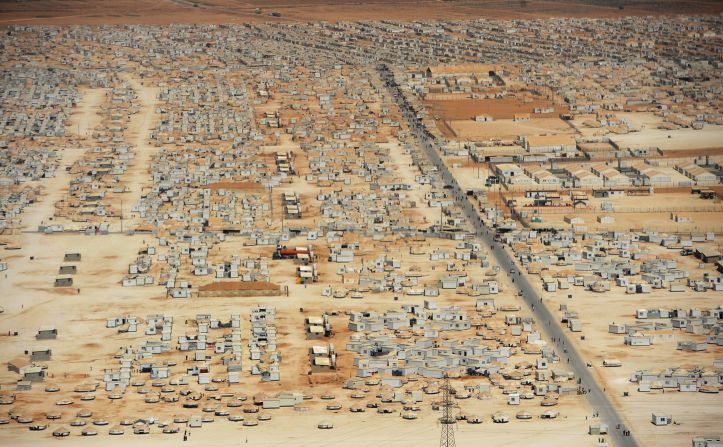

Last month at Zaatari, the second-largest refugee camp in the world, I met an accountant who carried his 6-day-old baby across the Jordanian border from Syria, and a mother who cannot find her 20-year-old son – and knows all too well what has likely happened to him. I saw parents too frightened to let their children out of their sight, even to go to school.

And while visiting Syrian refugees recovering in a hospital in Amman, Jordan from some of the violence that perhaps foreshadowed the August 21 chemical attacks on Syrian citizens, I spoke with a woman whose daughter died in her arms. These refugees’ stories, interspersed with images of white-shrouded children lying dead – poisoned in the Damascus suburbs – have stayed fresh in my mind.

The debates in the press over the past three weeks imply that whether or not the United States and its allies apply “lethal force” in Syria is the defining question of this crisis. Whether the United States intervenes militarily is a hugely important question – politically, strategically, legally and morally. But it is not the only one. For the civilians bearing the staggering weight of this war, it is not even the most pressing one.

The war has raised a huge range of unanswered questions and challenges for humanitarian actors that will persist long after any “symbolic” or even intensive military operation. These are imperative to Syrians’ survival and the region’s long-term stability and must not be crowded out as politicians and pundits wrangle over the use of force.

First and foremost is the question of how to keep borders open for refugees. More than 2 million Syrian refugees have now fled their country. The hospitality of Syria’s neighboring states towards these refugees has been breathtaking.

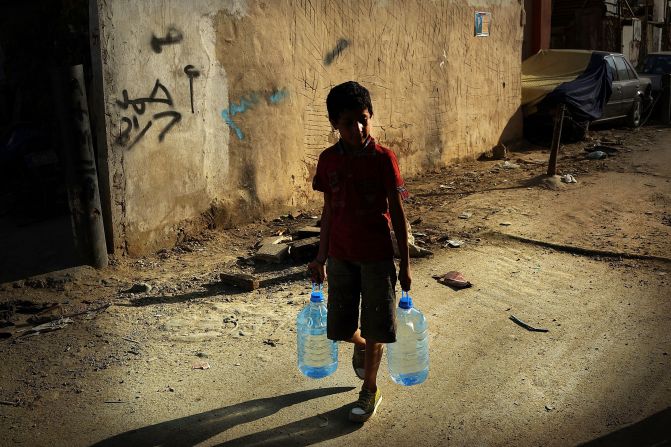

For example, more than one in four people in Lebanon today are Syrian, representing a level of generosity toward refugees that has never been matched by any Western state. Yet – particularly in Lebanon and Jordan – the refugee crisis has resulted in higher rents, reduced wages, overstretched social services, and increased pressure on already limited water supplies. All this has ratcheted up local tensions, and increased pressure on governments to limit arrivals.

While the Jordanian border remains officially open, over the summer UN officials reported “artificially low” arrivals, suggesting that would-be refugees may be encountering obstacles to their escape. Hurdles are also emerging for Syrians wishing to cross the Lebanese border. As the crisis escalates, redoubled international support is needed to ensure Syria’s neighbors can accept new arrivals. This support must benefit not only the refugees but also the communities that are hosting them.

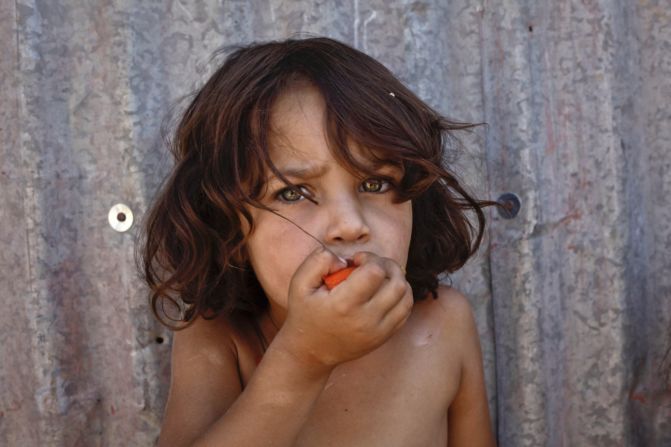

A second, related question is how to get Syrian refugee children into school. Last month – it really was a hellish month – marked what the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees called a “shameful milestone”: The number of Syrian refugee children reached 1 million. Many of these children are not in school (by some estimates, 75% of children in Zaatari are not in school) and have already missed months if not years of schooling inside Syria before fleeing abroad.

Some kids are not attending school because they are working to support their families; other refugee children living in towns and cities lack the money to get to school, or are afraid of harassment. As bombs drop, getting kids in school may not seem that urgent, but the long-term impacts of a “lost generation” of Syrian children would be disastrous.

Deprived of educational opportunities, these children are at risk of future unemployment, social marginalization and frustration, potentially prompting them to turn to extremist causes. More attention and assistance is needed inside and outside the camps to overcome the barriers that are keeping refugee children out of class.

Equally important is the question of how to do more to assist the estimated 5.1 million Syrians who are displaced within their own country. Two million of these are minors, and many are at risk of physical violence and forced recruitment. The internally displaced are much more difficult for humanitarian groups to reach, and are out of the media spotlight, which is trained on refugee camps and settlements in neighboring states. But we need to be asking what new and creative ways can be found to improve protection and support for this population.

Last, but certainly not least, is the question of how to strengthen Syria’s democratic opposition. This is not just a matter of access to weapons and military training, but the development of civil society organizations. Many Syrian refugees have already banded together to support others inside and outside Syria, including through the provision of medical assistance. We need to be asking what more can be done to strengthen and scale up such laudable initiatives.

Despite the devastation they are enduring, the Syrian refugees I met in Jordan are proud, industrious people. They have the capacity to recover and eventually rebuild their country – but if Western countries are to effectively support them, we can’t let the use of force become the only question on the agenda.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Megan Bradley.