Story highlights

Air Force crew recall their launch of a Minuteman ICBM from an airplane

Expert: It "broke with anything that had been done with ballistic missiles before -- or since"

Minuteman missiles were built to carry nuclear warheads

The C-5 Galaxy jet will be the first of its type to be retired to a museum

For more than four decades it has ranked among the largest, most useful planes in the Pentagon’s arsenal, but a C-5 Galaxy has never been retired to any museum. That’s about to change.

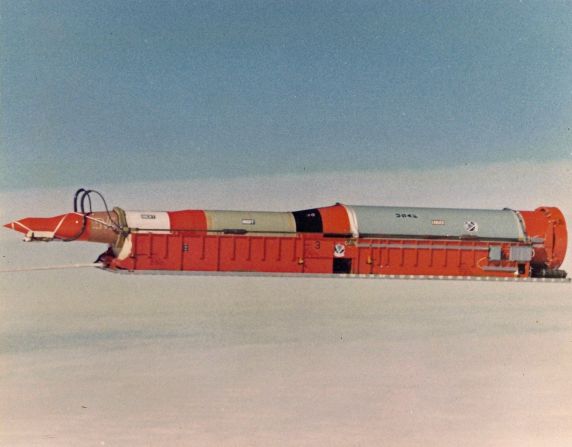

The behemoth nicknamed Zero-One-Four arrived at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware Wednesday, where it soon will be handed over to the Air Mobility Command Museum. The giant jet with 90014 painted on its tail made history in 1974 when it became the only aircraft ever to drop and ignite a live, Minuteman intercontinental ballistic missile.

Yep, that’s correct – it launched the Cold War weapon that was designed to wreak unspeakable nuclear annihilation. Of course, this particular missile was unarmed.

If it seems odd that a plane would unleash a gigantic hammer like a Minuteman – well, it is. These missiles weren’t supposed to launch from airplanes. They were supposed to blast off from underground silos.

Airplanes: The big ones

“It was radical,” said nuclear weapons expert Hans Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists. “It broke with anything that had been done with ballistic missiles before – or since.” The idea of launching Minutemen via airplanes was an attempt to protect U.S. missiles from being destroyed by enemy missiles, Kristensen said, because the Soviet Union would have had a hard time targeting Minutemen traveling aboard airplanes like the C-5.

With three stages, the Minuteman measured 56 feet and weighed 86,000 pounds. Never before had the C-5 – one of the biggest planes in the world – ever dropped such a heavy load.

Related: Stalking the world’s biggest planes

On October 24, 1974, at Utah’s Hill Air Force Base, airmen and crew from manufacturers Lockheed and Boeing, boarded Zero-One-Four.

Among them, Chief Master Sgt. James Sims, who watched the whole thing from the C-5’s cargo hold – the best seat in the house.

“There was inherent danger in it,” said Sims, describing the mission. The Minuteman was attached to a special cradle designed to be released on a track leading out the plane’s rear cargo exit. Parachutes would drag the missile out of the plane and then point it upward. A timer, Sims said, would spark the rocket’s fiery engines.

The risks were significant. If the Minuteman exited the plane incorrectly it could dangerously push the C-5’s nose upward, making it difficult to control. Another risk: the missile could accidentally become wedged in the aircraft’s infrastructure, shifting the plane’s center of gravity and – in a worst-case scenario – trigger a crash.

As the C-5 reached its test range off California about 20,000 feet over the Pacific, its four powerful jet engines were singing their signature whine. With the drop zone only eight minutes away, the huge rear cargo door opened, exposing Sims and his crew mate, Technical Sgt. Elmer Hardin, to the roaring wind.

Soon it was go time. The missile and its cradle were released. Parachutes dragged the 43-ton payload along its track down the 121-foot cargo hold until it toppled off into oblivion. Hardin felt the giant plane begin to tip.

“You did come off the floor a bit,” he told the Air Mobility Command Museum Foundation’s “Hangar Digest” magazine. “It was like dumping a wheelbarrow full of water.”

The chutes tilted the missile vertical as it fell thousands of feet and disappeared into the clouds underneath.

Then, nothing.

For a minute Sims thought something was wrong.

Suddenly from below, Sims saw plumes of smoke and flame. “It came blasting through the clouds and you got a good view of it,” Sims said. It rocketed to 30,000 feet – 10,000 feet above the C-5, as Sims remembers it. “It looked like a missile launch from Cape Canaveral,” he said. It burned for about 25 seconds, he recalled, and then “cascaded into the Pacific Ocean.”

“Everything worked as advertised,” he said. “I was elated. … It was special.”

YouTube has Air Force film of the test

Although the mid-air missile launch worked, the Pentagon never adopted the concept. Skeptics likely would have seen the project as “a little crazy,” Kristensen said, because it was technically very risky and would have been operationally very expensive to implement on a wider, more permanent scale. It was a “wild card dream,” he said.

At the time, the idea wasn’t really outside the box, said Fritz W. Ermarth, a nuclear strategy expert, ex-CIA analyst and former adviser to President Ronald Reagan. Pulling a missile out of an aircraft “on a sled with parachutes was far from rocket science,” Ermarth said. But war planners of the era were expected to invent new options to protect the nation’s nuclear weapons arsenal.

Kristensen credited the project to a “sort of Cold War euphoria in those days that spurred people to come up with these sort of ideas.”

Many wonder if the C-5 Minuteman demonstration was simply a stunt intended to show strength at a time when the Soviets were negotiating with Washington over a proposed nuclear arms treaty.

It wasn’t ever officially announced, said Pat O’Brien, an engineer on the project, “but we felt they were trying to use this as a bargaining tool for the SALT II (Strategic Arms Limitation) Talks.”

Retired Air Force crew chief Rodney Moore, who helped maintain Zero-One-Four during its Dover heyday, wanted to go on that mission. He asked to take part, but was turned down. “I was disappointed,” he recalls. Even all these years later, Moore says he still wishes he had pressed harder for permission.

“I loved that airplane,” said Moore.

As its primary crew chief, Moore inspected the aircraft before each flight. He marshaled it to Dover’s runways and then watched it take off. “For a very short period of time, I was a part of that airplane’s career,” Moore says. “And it was a major part of my life.”

Moore, who hasn’t seen Zero-One-Four in 30 years, looks forward to the jet’s dedication ceremony, set for this fall. “I’m going to have some emotions about it,” Moore admits. “I know I’m gonna feel pride.”

“It’s going to be like a reunion with an old friend.”

Journalist Jeff Brown contributed to this report.