Story highlights

Traumatic circumstance complicates the normal grieving process

Children learn to grieve by watching adults and asking questions

Images -- in drawings or photos -- can help children vocalize their grief

“Obliterative.” It’s the best description Natalie Norton of Laie, Hawaii, has heard of what grief is like.

In January 2010, after suffering from whooping cough for less than a month, Norton’s infant son, Gavin, passed away. She held Gavin in her arms at the hospital as her husband, Richard, placed his hand over his son’s heart, feeling its last beat.

“We imagine (grief) will be difficult, we imagine it will be challenging and unfamiliar and lonely, but we don’t imagine that it will be, in the words of Joan Didion, ‘obliterative,’ ” she said.

Almost as horrifying, she said, was when she and Richard had to tell their three other sons that their brother was not coming home.

Walking children through the stages of grief is a challenge many parents have never faced and one they may not have the tools to tackle.

As the children of Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut, returned to school last week after the deaths of 20 of their classmates and six of the school’s staff, the school year may be back on track, but things are hardly back to normal.

For children, finding concrete ways to remember the person they’ve lost and vocalize their grief can be therapeutic, said psychologist and trauma specialist Therese Rando. “There are literally 43 separate sets of factors that combine to determine how a person mourns.”

Memorializing lost loved ones can help them move forward in the process.

Traumatic deaths like those in Newtown can further complicate mourning.

“The essence of trauma is powerlessness,” Rando said. Survivors are left many questions: “What can I count on?” “Who am I in the absence of my loved one?”

One question parents should ask is how they can empower their children to speak about traumatic events and remember the person they lost. The Nortons encourage their boys to speak openly about their baby brother.

“When people ask us how many children we have,” Richard Norton said, “it’s easier to just say three. But our sons will say, ‘There’s four; Gavin died.’

“It’s important to them.”

When terrible things happen: Helping children heal

Veronica Richardson of Powder Springs, Georgia, knows firsthand that explaining a sudden and unexpected death to children can leave a parent at a loss for words.

Ten years ago, when her two sons were 3 and 5, their father, Corey Fields, committed suicide.

“Your father had an accident, and he passed away. He’s now an angel. He’s now a star in the sky,” Richardson told her boys.

She didn’t know how else to describe their father’s death.

Richardson, now a mother of four, made sure her sons felt free to talk about their father. Even when she remarried, it was not taboo to discuss him or mention his name.

“If they wanted to ask what his favorite color was, what kind of music he liked to listen to, what his favorite food was, it was OK to talk about their father,” she said. They found comfort in asking questions, she said.

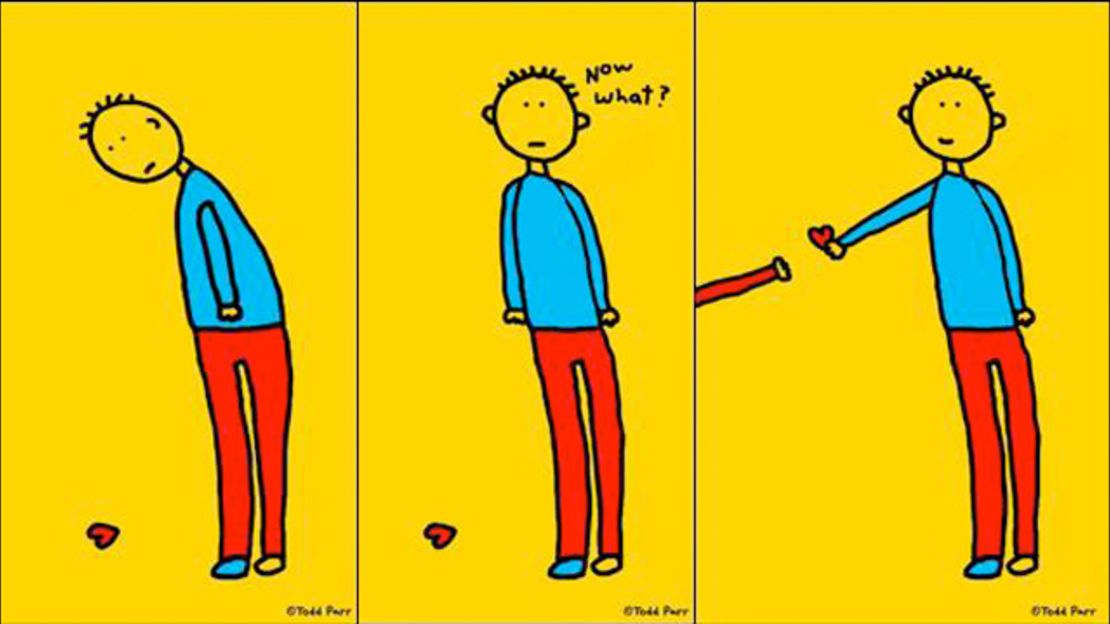

Children ask a lot of questions about death, said author and artist Todd Parr, who is known for communicating complicated messages to children through simple illustrations. (His book titles include “It’s OK to Be Different,” “The I’m Not Scared Book” and “The Feelings Book.”) His illustrations are often a springboard for children to more easily discuss their emotions.

Parr’s pet pit bull, Bully, featured prominently in his books and became an emissary in his mission to communicate with kids.

Children who grew up reading his books have told Parr they would kiss pictures of Bully goodnight. When he tours elementary schools, students ask, “What happened to Bully?”

“I don’t want to tell kids that Bully died and make them feel sad,” Parr said, “and yet I don’t have another answer. Bully died and went to doggy heaven.”

Should you tell your kids about Newtown?

He’s found that stating the facts plainly and reassuring kids that he’s there for them is part of the recovery.

The Nortons used family photos as a tool as they grieved for baby Gavin.

“We’re looking at a photo of Gavin right now that our sons taped on the wall,” Richard Norton, 32, said over the phone from Arizona, where his family has joined him while he works on a business degree.

“Images are important,” he said. “(Gavin’s) around. He’s not forgotten. It sparks conversation.”

When the Nortons sat their kids down individually to tell them about Gavin’s death, they tried to be mindful of each child’s maturity level. Their oldest had just turned 6, their middle child was turning 5, and their littlest was 3.

“We used different language with our 6-year-old than we did with our 3-year-old,” said Natalie Norton, 31.

“One thing we did right is, we made it very clear to the children that no matter what they felt, it was OK,” she added. “We repeated those words to them. If you’re happy, it’s OK to be happy. If you’re angry, it’s OK to be angry. There’s no shame or embarrassment.”

As parents, the Nortons told themselves the same thing: that there was no such thing as an inappropriate response.

“We cried openly in front of the children,” Natalie Norton said. “Behind closed doors, I broke down and acted like a lunatic.”

Support crucial for kids after trauma

Setting an example of grief and mourning for children is crucial to their development, Rando said. In addition to asking questions, children learn from watching adults. Public examples of grief are instructive for children, but they may not always learn an appropriate lesson.

As attention after Newtown focuses on hot-button issues such as gun control and mental health, children are witnessing anger in response to tragedy.

“We’re outraged by what has happened, which is an appropriate reaction,” Rando said, but when children witness the devolution of dialogue into aggression and vitriol, it can cause even more damage. Unless children can see examples of respectful conversation following a traumatic event, adults will only be perpetuating aggression, she said.

Children are also seeing examples of adults concerned for the families and community of Newton and wanting to help them. This teaches compassion and positive action as a step in grieving, Rando said.

Richardson, 34, is providing her children with just such an example.

When she learned that Sandy Hook students and teachers were going to attend a school in a neighboring county, she took action to make them feel more at home. Knowing that the teachers would be without the supplies from their old classrooms and the students probably no longer had backpacks, Richardson focused on collecting school supplies to send to Connecticut.

Modeling productive behavior for kids in the face of grief is one way to help them understand it’s a part of life, according to Rando.

“It’s not just about having an initial reaction and then kind of just petering out,” she said.