Editor’s Note: CNN’s “Great Buildings” showcases six of the world’s leading architects. We asked them to name the favorite building they have designed and to choose a piece of architecture they wished they had created.

Story highlights

Daniel Libeskind's redesign of the Military History Museum in Dresden is his favorite work to date

"It's not just about weapons and rockets ... it's about people's decisions and how people view the world," Libeskind says

Polish-born architect wishes he had designed the Eiffel Tower, in Paris

"It's completely uncharacteristic of Paris, and yet it's such a fantastic building," he says

Daniel Libeskind, the Polish-American architect responsible for the World Trade Center site’s redevelopment, says his favorite building is the Military History Museum in Dresden, Germany.

Originally an armory for Kaiser Wilhelm I and subsequently under Nazi and Soviet control, the Bundeswehr’s main military museum survived the 1945 bombing of Dresden due to its location on the city’s outskirts.

“It is an interesting project for me,” says Libeskind, “because now it is a museum of modern democratic Germany. How to transform it? How to create a new sense of what it means to have a military in a democracy which is controlled by the citizens?”

In Libeskind’s $85 million redesign, completed in 2011, a huge wedge of concrete and steel scythes through the stone, columned building, to create something he describes as “both disruptive of the old, but [that] also gives you a sense of how we have changed our thinking.”

Watch Great Buildings on CNN’s Connect the World

Born in Poland, raised under Communist regimes and the child of Holocaust survivors, Libeskind says the concept underpinning his design “wasn’t something that I had to research in libraries.”

The dramatic shard, which was constructed as the building was also being restored, helps to reorient the museum’s purpose.

Libeskind says the new space offers visitors a chance to question “why people participate in and organize violence, why they conform to totalitarian thoughts.”

View a hi-res gallery of Libekind’s ‘Great Buildings’

“This space is not for weapons. It’s to navigate between the horizontal world of history and the vertical world of human aspiration and understanding.”

“I wanted people to feel that sense of displacement, that space of catastrophe,” he says. “It’s not just about weapons and rockets and tanks, it’s about people’s decisions, and how people view the world.”

The building Libeskind most wishes he’d designed is one completely at odds with its surrounds – the Eiffel Tower, which looms over Paris’ uniformly mid-rise cityscape.

“It’s a building with no function, that has no program,” Libeskind says. “It’s completely uncharacteristic of Paris, and yet it’s such a fantastic building.

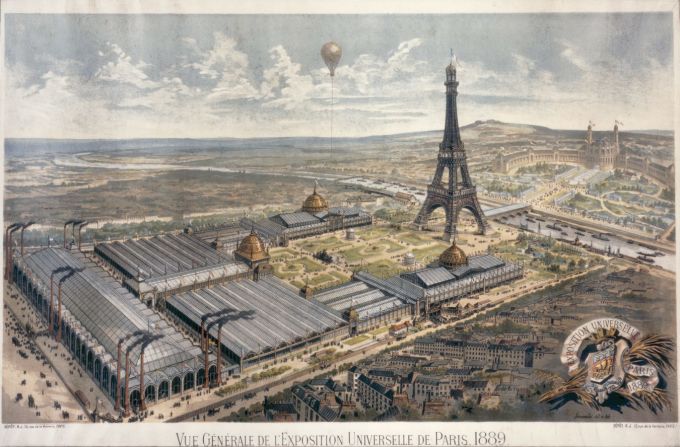

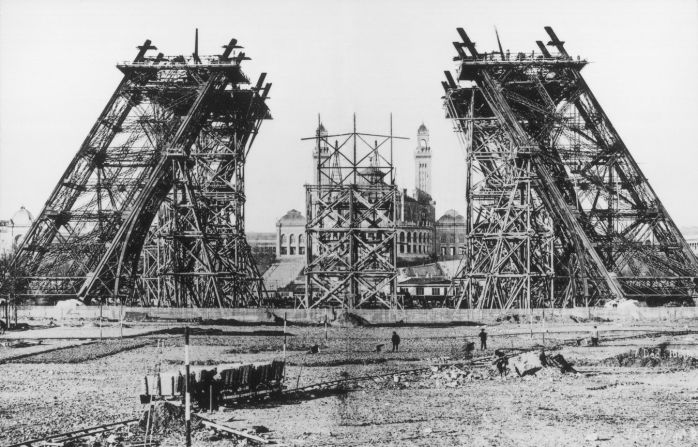

Today it’s one of the world’s most recognizable and most-visited monuments but in its day, the tower, erected for the 1889 World’s Fair, was a controversial emblem of industrialization.

Libeskind admires the daring of its design, which was innovative for its time, and the risks its engineers took – “the technology had never really been used. There is no guarantee how it would work,” he notes – but he also admires its poetry.

“It doesn’t mimic anything. It’s original. It has a spirit to it, a spirit of the unknown. And when you go see it, you still wonder, what the hell is this thing? How was it built?”

“That defines for me what good architecture is: It’s not a formula. It’s not the pretty facade of the building. It’s how the building transforms the city. It’s changed how people view Paris.”

“All the great artists, composers and politicians hated that building. They wanted to tear it down. They thought it was the ugliest, stupidest thing. But, in the long run, it became the most beloved and most symbolic building of France, of Paris, of Europe.”

Libeskind’s Dresden museum was also criticized but, he says, he never doubted it.

“Once you hit on the right idea, it’s not a matter of compromising. Of course, you have to be flexible to work it out, but the big idea has to be so strong, it has to go through fire and still emerge exactly how you wanted it to be.”

“If people enjoy it, the building becomes part of the city, and then people have a different idea of the city. It can have a big role in changing what the world looks like to us.”