Story highlights

Florence Griffith-Joyner shocked the world when she won 100 and 200m gold at Seoul 1988

In that year she smashed both world records, which still stand today

Flo Jo had been dogged by unfounded drug allegations until her death in 1998

CNN speaks to her coach and husband Al Joyner about Seoul, drugs and her legacy

When Florence Griffith-Joyner signed up for her 1988 Olympic 100 meter trial in Indianapolis, few expected fireworks. But those who were there to witness her quarterfinal run couldn’t comprehend what they were seeing.

Flo Jo, as she would later become known, had been a good, but not exceptional, 200 meter sprinter over the past seven years. She had failed to qualify for the boycotted 1980 Moscow Olympics but had won silver at the Los Angeles games four years later. She hadn’t run the 100 meters, not seriously, until now.

The next ten-and-a-half seconds encapsulated everything that would define Flo Jo for the rest of her life

Speed, elegance, beauty, femininity, suspicion.

She got off to an indifferent start but at 60 meters found a different gear and destroyed the field in a way unseen in women’s sprinting. By the time she crossed the finishing line she had recorded a time of 10.49 seconds, almost four hundredths of a second quicker than her previous best before the trial, and a new world record.

She had smashed it wearing her self-designed, one-legged jump suit and sporting her trademark mane of dark hair and long, painted finger nails. The commentator on American TV was dumbstruck.

“I…it can’t be, nobody can run that fast,” he stuttered when hearing the anemometer had recorded a legal wind speed.

“They must have done something to the electronics because she won by such a margin … it might be right but 10.4(9) … is incredible.”

But the electronics, even if there was a suspicion of a fault, were deemed infallible and the record stood.

The taint of drugs

Looking back at that moment her husband and then coach, the Olympic gold medal winning triple jumper Al Joyner, laughs when he recalls the reaction to the record.

“At first, when she beat the record, they said it was wind assisted,” he exasperated. “Later when she won the medals they said it was drugs.”

The run was a prelude to that other unforgettable sprint performance at Seoul. Ben Johnson’s brutal world record and subsequent ban for testing positive for steroids cast a long shadow over the Games, and an even longer one over Flo Jo.

She won gold in the 100 and 200 meters. In any era she would be hailed as the greatest of all time, a sprinter who transformed her discipline in the same way Usain Bolt has transformed his.

But her improvement was so great, her times so exceptional, the change in her physique so profound that, for most, drugs – steroids – was the only answer.

“It was jealousy,” Joyner tells CNN, denying that Flo Jo ever took drugs.

“I trained her like a man. We did a lot of things then that they do now with nutrition. The things that separated her were her mental focus and toughness. She was humble. My wife was great then and she is great now.”

A humble start

Florence Griffith was the seventh of eleven children brought up in Jordan Downs, a run-down public housing complex in Los Angeles.

Her running ability at 200 and 400 meters got her to college but she dropped out to become a bank clerk and part time hair stylist to support her family. It was only when she managed to secure a meager sponsorship that she could start to take running seriously. Joyner still vividly remembers seeing his future wife for the first time.

“I met her at the U.S. Olympic trial in 1980. It was 6.45pm. I remember that because I never saw a woman look like that before; she made me speechless,” he recalls.

“Jackie [Joyner-Kersee, his Olympic gold medal winning sister] was going through UCLA. Eventually I came back out to train. I’m doing distance running. So we start running together and started being friends. She’s was not only beautiful, but she could run. I thought I could run off and leave her but I couldn’t shake her.”

The two married in 1987 and it was this emotional and financial stability that Joyner credits, in part, to the huge jump that Flo Jo made between that year and 1988.

“Florence gave a lot of her love. I was the person that gave the love back,” he says. “She needed to know trust and faith and belief.”

The other ingredient, according to Joyner, was purchased in a local K-Mart.

“We bought a $150 leg exercise machine and she did leg curls every night. More than 20 lbs every night to build up the strength in her legs. She was working 12 hours a day.”

Seoul 1988

Flo Jo’s incredible run at the U.S. Olympic Trials had made her an object of suspicion when she arrived at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, compounded by the shocking news of Ben Johnson’s fall from grace.

Her preparations hadn’t been great. She ran an 11 second plus time at a meeting in Sweden and then, according to Joyner “10.89 in Gateshead, London (sic).” Although, on closer examination, that was into a headwind and was still as fast as British sprinter Linford Christie could muster, the man who won silver in the men’s 100 meters.

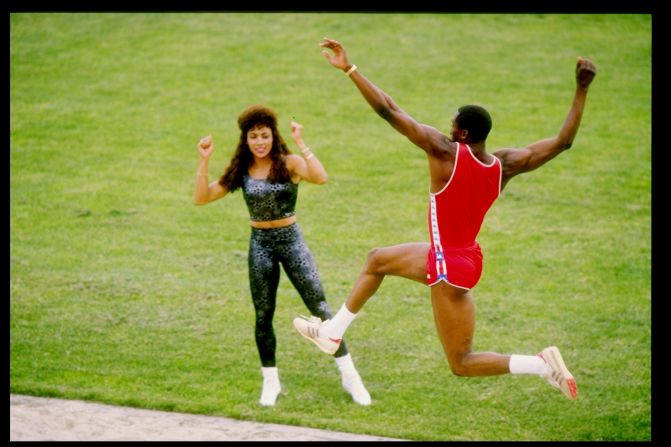

But Flo Jo breezed through the heats at the Games, recording a clean sweep of sub-11 second times when she won a wind assisted final in 10.54 seconds. Again she had an average start but burst free at 60 meters, annihilating the rest of the field. She was handed the Stars and Stripes and headed towards her husband.

“I feel so good that it’s over,” she said moments afterward. “I wasn’t chasing the time, I was chasing the win. A gold, that’s the first for me at the Olympics and I just thank God that it’s over.”

Al Joyner was beaming by her side.

“Seeing my wife run 10.54…” he said, still a little shocked. “I predicted 10.57 but she always wants to run a little ahead of me. It brought tears to me.”

But behind the scenes the suspicion had led to a string of drug tests for Flo Jo, tests which Joyner used as motivation for his wife.

“She was being tested and I felt people were trying to get into her head, I had to keep her focused,” he says. “I told her: “Go out there and run like you on jet fuel.”

Her next run in the 200 meters was even more remarkable. She smashed her own world record. Both her 100 and 200 meter records still stand today, unbroken.

“We performed all possible and imaginable analyses on her,” the president of the International Olympic Committee’s medical commission, Prince Alexandre de Mérode, said at the time.

“We never found anything. There should not be the slightest suspicion.”

A clean slate?

Florence Griffith-Joyner never did fail a drugs test. Seoul would be her last Olympics. She retired afterward with a press conference at Madison Square Garden.

Her detractors point to the fact she retired just as compulsory random drug testing was being introduced. But Joyner insists she left the sport to have a family. Her only daughter was born in 1990.

Talk of a comeback at the 1996 Olympics came and then went when she had a seizure that same year.

Two years later she died in her sleep. She was 38 years old.

“We were dazzled by her speed, humbled by her talent and captivated by her style,” President Clinton said.

“That was September 21, I was getting ready to take my daughter to school and I hear my wife’s alarm clock,” recalls Joyner, who refers to Flo Jo in the present tense throughout.

“I turn off the alarm clock and my wife’s not moving. It was devastating looking at my daughter. She was seven. When I see the Olympic Games now it brings joy to me, all her hard work. They can say what they want to say.”

Flo Jo had suffocated during an epileptic seizure. At first her death at such a young age seemed to prove the suspicion of steroid use. There was intense interest in the autopsy.

“I had to do my grieving in front of the whole world,” says Joyner, only finding any measure of comfort “30 days later after my wife’s autopsy.”

The results in death, just as in life, had proven Flo Jo right. There was no conclusive proof of drug use.

“I told the doctor, they checked for everything,” he says. “They had people coming up all the time wanting to do tests. My wife passed the ultimate drugs test.”

Taking back Fl Jo

Florence Griffith Joyner is rarely mentioned without an invisible asterisk next to her name when the women’s 100 and 200 meters comes around in Olympic year.

Current runners bemoan the unreachable bench mark she set. Double Olympic 200 meter gold medalist Veronica Campbell Brown got nowhere near it, saying it was beyond her reach.

Former 200 meter Olympic champion Gwen Torrence said that she “did not acknowledge those records … To me they don’t exist and women sprinters are suffering as a result of what she did to the times in the 100 and 200.”

Yet her impact on the sport is there for all to see.

“Every time you see a woman in the 100 or 200 meters with make-up and nails, that’s Florence,” says Joyner of his wife’s legacy.

“She did it with style and she did it with speed. She was in a class by herself especially for all the women she opened the door for. Her star will always shine. And it has the right to shine.”