Story highlights

Cee Cee Davis says she lost 20-30 friends to violence during high school

New Orleans had almost a murder a day in January, after locking 2011 Murder City title

Pastor keeps running list of city murder victims' names in front of church in the Treme

Mother who lost all 4 sons to gun violence says race a driving factor in city's killings

Curissa “Cee Cee” Davis doesn’t trust men, and she’s slow to make friends. She can’t remember the last time she did something fun.

It’s not that she’s antisocial; the former Carver High student body president is quite gregarious once she starts talking. But after losing at least 20 friends to gun violence before she turned 18 in June, it’s difficult for her to get close to people when there’s a good chance they’ll be killed.

“Why would you want to make a new friend?” she said. “You still interact with people, but you don’t get as close to them as you would.”

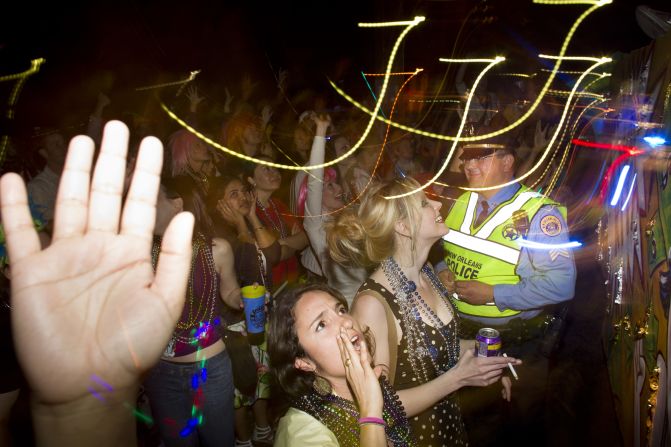

The revelry of Mardi Gras is over, and so is a series of high-profile pro and college football games that had people dancing in the streets, yet with nearly a slaying a day in January, not all city residents feel like celebrating.

The mayor has called murder “the single-most important issue facing our city.” Since Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans has racked up six straight titles as the most murderous city in America. January suggested a seventh was coming, though the pace of the killings slowed considerably in February.

Read how the murders have created an unlikely industry

With one of every 1,700 residents slain last year, the murders are not far from people’s minds. Bartenders, pastors, students, artists, lawyers – it seems nearly everyone has an opinion on the cause of the problem, or how to solve it.

Many point to poverty and the accessibility of guns. A mother who lost all four of her sons to violence says race is a driving factor. A police chief wants families to step up as he works to rebuild relationships with communities after decades of corruption. A pastor puts every victim’s name on a board outside his church, which helps run an art program to give at-risk kids ways to express themselves. Meanwhile, a neighborhood youth center breaks down barriers with pizza and basketball.

Getting to the youth seems integral to any solution. Of the 26 slayings in January, more than half the victims hadn’t seen their 30th birthdays. Keian Ester was only 11, playing video games when a bullet pierced an apartment wall and then his eye. Keian died the next day.

It’s the type of senselessness Cee Cee Davis wanted to escape when she recently moved a few miles west to Metairie. Growing up in the 9th Ward, she doesn’t know exactly how many friends she lost in high school, somewhere between 20 and 30. She has tried so hard to forget the pain she has trouble naming them all.

One she will never forget is Katie, whose name is tattooed inside her forearm between angel wings. A halo is sketched above the letters R.I.P.

When Davis was 14, she and Katie were inseparable. They both loved fashion. They’d pick out each other’s outfits and do each other’s hair.

“It just fit. We just loved to be around each other,” Davis said.

The only thing Davis didn’t like was Katie’s boyfriend. Kevin seemed insecure and controlling. Davis would tell Katie she didn’t need him, that she was better than that. Katie eventually heeded Davis’ words and told Kevin they were through.

Kevin responded by shooting Katie in the back with a shotgun and leaving with an ex-girlfriend. When authorities arrived, 17-year-old Kelly “Katie” Brittany Hill was dead in his bedroom.

Davis’ mother woke her at 4 a.m. with the news. Davis was confused. She checked her phone. If Katie were in trouble, she would have called.

“I just dropped the phone and started crying,” she said. “Ten missed calls. That’s what killed me. I was in a dead dream, and I didn’t hear my phone.”

Today, Davis doesn’t sleep at night. When she’s able to nod off during the day, she dreams about people getting hurt – sometimes herself, sometimes her mother and brother. She brushes off the notion it has anything to do with Katie. Her brother, 24, has the same problem.

“We’ll both be up all night,” she said, “like two vampires.”

‘Struck by their ordinariness’

Davis tries to list her other dead friends but doesn’t get far: Winky. Brandon. Christian. Desmond. Elton. Christopher.

Christopher, 17, stands out, too. He was also a close friend. Smart and good with computers, he loved working on his ’03 Impala. He would give Davis rides, and they went to the movies together.

She was 16 when the Impala became his undoing. After an argument over cars, he was carjacked at gunpoint, shot multiple times, and his body was dumped on the shoulder off Chef Menteur Highway. Two 19-year-olds were arrested but later found not guilty.

The pettiness that leads to murder is a twisted trademark of New Orleans’ violence. Davis remembers youngsters losing their lives over the 2009 re-release of the Air Jordan “Space Jam” sneaker.

“For just the damnedest of reasons, people kill each other,” Police Superintendent Ronal Serpas said.

While there are plenty of killings over drugs, revenge or disrespect, there is an astonishing rate of what Serpas calls “uncommon endings to very common fights.”

Indeed, researchers conducting a federally funded crime study last year wrote that murder in the Big Easy is a different animal.

“What appears to be different about homicides in New Orleans are the circumstances of the events – they are in residential areas and outdoors and do not involve the kinds of drug and gang involvements found in other cities,” the researchers said. “In reading the narratives of the offenses, one is struck by their ordinariness – arguments and disputes that escalate into homicide.”

In 200 murder cases selected from a 13-month span between April 2009 and May 2010, the study found 57 were tied to drugs, while 47 were acts of revenge. Gangs were almost never a factor. Arguments led to 37 killings.

When Mayor Mitch Landrieu announced in April that curbing the city’s murder rates was priority No. 1, he offered a harrowing assessment of the crimes and their victims.

“By the time you wake up tomorrow morning, I will have likely received another message – the worst part of my day – that says exactly the same thing: ‘Mr. Mayor, we are sorry to inform you that earlier this evening, police officers responded to gunshots. When they arrived on the scene, they found a young, African-American male face down in blood, gunshots in the back of his head. He was pronounced dead on arrival. There. Are. No. Witnesses.’ “

It was barely an overstatement.

The federally funded crime study showed that almost 87% of victims were male and 91.5% were black. Ninety percent were killed with firearms. Forty percent were in their 20s, 13.5% their teens.

Like the people who killed them, the victims often had histories of violence, drugs or gun crime.

Landrieu said there are rarely witnesses, but the study notes there are often witnesses, they just won’t talk.

The reason: Many in the community don’t trust the police. When Landrieu took office in May 2010, he wrote U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder to say he had “one of the worst police departments in the country.” A year later, the Justice Department issued a scathing report citing the NOPD’s “patterns of misconduct that violate the Constitution and federal law.”

The report wasn’t talking merely about high-profile cases such as the Danziger Bridge incident, in which officers were convicted of fatally shooting unarmed civilians. The misconduct was far more deeply rooted, the report said.

“NOPD’s failure to ensure that its officers routinely respect the Constitution and the rule of law undermines trust within the very communities whose cooperation the department most needs to enforce the law and prevent crime. As systematic violations of civil rights erode public confidence, policing becomes more difficult, less safe, and less effective, and crime increases,” the report said.

Read the Justice Department report in PDF format

In the federally funded crime study, just over half of the 200 cases were closed by an arrest or the suspect’s death. The study also noted that since Katrina there has been a “series of arrests and convictions of police officers that undermined trust, especially in minority communities.”

Many in the city’s minority communities say there wasn’t an enormous amount of trust before the storm.

Four sons, four funerals

Althea Phillips is among them. Since 1992, all four of her sons have been killed.

Only one killing was solved, that of Leniel Phillips, 29, who stood 4-foot-11 and went by “Shorty.” He was killed in a 2005 fight with his wife’s ex in Lafayette. The other three slayings – still unsolved – took place in New Orleans.

“I miss my children so much that it’s unbearable. It takes me to the bed, the pain and the grief that I feel. I don’t feel comfortable in this house anymore,” she said at her St. Roch home. “When are (they) going to get (the killers)? When am I going to see them on the news? I want them to be held accountable for what they’ve done. They shattered my life – again.”

Her son Kimbro Washington, 22, a restaurant manager in training, was fatally shot after an argument in 1992. Leonard Phillips Jr. also was 22 when he was killed with an AK-47 at close range in 1995.

Lamont Phillips, 34, was killed last month. Though he served eight years on a drug charge, his mother said he had kicked a heroin habit. Since his release five years ago, he was attending classes at a community college and working on a plumbing apprenticeship. Clever and good-looking, he made his mother proud.

She was devastated January 4 to learn Lamont had been slain just down the street. Local media reports quoted police saying there were drugs at the murder scene. The family says they weren’t Lamont’s.

When police came to search her home, Althea Phillips passed out from the stress.

Serpas, who took the NOPD helm in May 2010, won’t let the police be the only scapegoat for the community’s lack of trust. He conceded there has been widespread corruption, “a failure to do effective police work and a failure to build cases” before his administration. He said ideally, he could use another 275 officers on the 1,300-strong force.

But the entire criminal justice system has been “inept,” not just the police, he said. The U.S. Supreme Court, for instance, recently reversed a quintuple-murder conviction after justices determined prosecutors withheld evidence in the case.

Serpas is working to rebuild trust, holding weekly community meetings in all eight police districts. In the summer, officers knocked on residents’ doors to introduce themselves and hand out crime-prevention literature.

Early successes include taking 5% more guns off the street in 2011 than in 2010 and a 20% increase in tips coming into the Crimestoppers hot line in that same period, the superintendent said.

Serpas and Landrieu have also spoken to local judges about increasing bail amounts in gun crimes, a tactic Serpas said reduced murders in St. Louis.

Tampa – 27Bakersfield – 33St. Louis – 144New Orleans – 175

Police are only a cog in a complicated machine that must fix New Orleans’ murder problem, if it’s to be fixed, Serpas said. Not only should families teach children more personal responsibility, he said, the city needs more job opportunities, better education and more recreational and after-school programs.

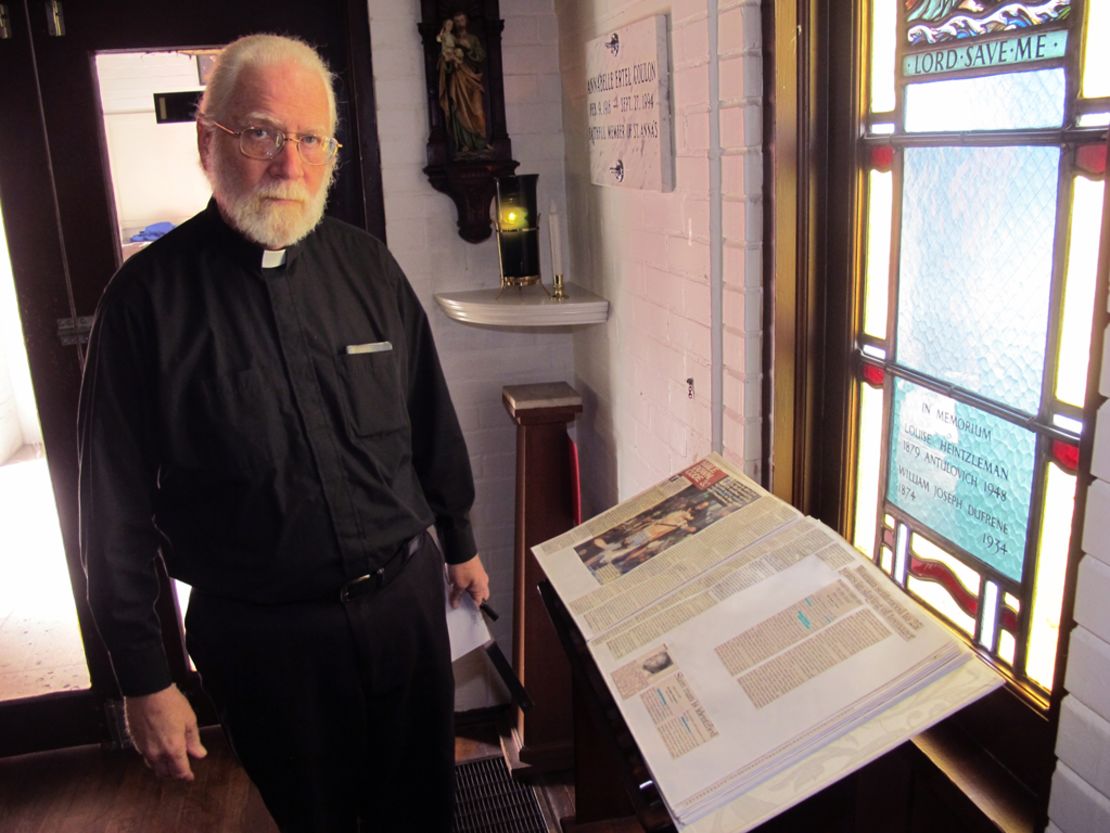

Father Bill Terry at St. Anna’s Episcopal Church cautions against a one-size-fits-all approach to New Orleans’ violence. Just because something worked in a similar sized city doesn’t mean it will work in the Big Easy, he said.

The city’s free spirit – a permissive vibe that has made it so easy for arts, food and music to thrive – has a flip side.

“The same thing that makes us the funkiest city in probably the world also gives us a laissez faire attitude toward violence,” said Terry, who was born Uptown. “It’s great for art, but what about curing poverty or rebuilding the city in an intelligent, structured way?”

Making every death matter

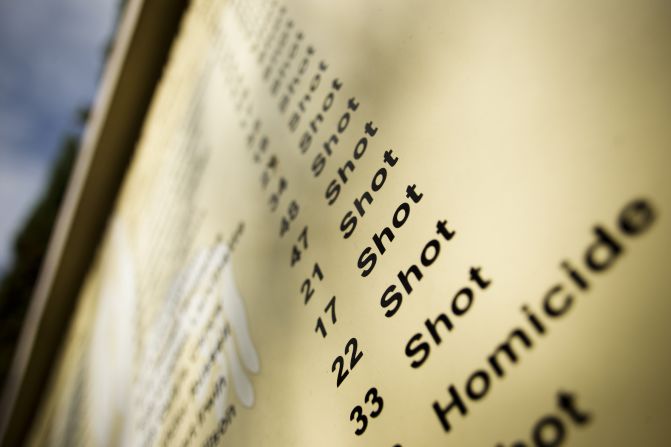

Terry became so fed up with the incessant killing that in 2007 he set up a “murder wall” outside the church. Every week, he updates the wall with the names of those slain in and around the city.

The wall, which contains more than 1,000 names, is stored piecemeal around the church because there is no room or money for a permanent monument.

Terry and his wife, Vicki, lost their 19-year-old daughter Tonya to suicide in 1993, so they know the sense of loss many parents are experiencing.

Bill Terry came up with the idea for the wall in July 2005 after a television news report about two murders startled Vicki. She asked him where the killings had happened. Terry told her not to worry; they were on the other side of town.

That night, the couple was awakened by gunshots. Terry ran outside to find a 17-year-old dead, slain in a drug deal, not 25 feet from the front door of their Bywater home.

Police wouldn’t allow Terry to administer the teen’s last rites, and the victim’s “girlfriend was wailing so loudly, it was like Irish keening,” Terry said.

He learned that night why fire trucks arrive on a murder scene: to wash away the blood.

“That’s when I realized it doesn’t matter where the murder is in the city,” he said. “We’re all responsible.”

On the murder wall, the victims are no longer statistics. They are people. With only their name, age, and date and manner of death (overwhelmingly, “shot”), it’s impossible to tell if they were rich or poor, 6th Ward or 10th Ward, black or white.

“Stop the conversation about racism and all that bulls***. Not that it doesn’t exist, but sometimes we run that up the flagpole instead of dealing with the central issues causing the violence. We can’t use that as an excuse not to act,” Terry said.

“Racism has less effect on a black kid who is articulate, who has self-esteem, self-respect, dignity and understands the boundaries of the world are not the 9th Ward and 7th Ward. The boundary of this world is their imagination.”

The wall, along with an adult education center, mobile medical unit, food pantry and arts school, is the church’s way of fighting the violence, Terry said. Though he speaks proudly of each initiative, he seems most smitten with the school.

A creative alternative

Anna’s Arts for Kids is headed by Darryl Durham, former executive of the renowned Harlem School of the Arts in New York City. Durham said the wall serves as an important teaching tool because it contains the names of many children who were the same ages as the 4- to 13-year-olds who make up his classes.

Art gives at-risk kids a way to express themselves rather than lash out, he said, but the key is getting kids off the streets, even if for only a few hours on Saturday.

He pointed to the case of a 2-year-old in the impoverished Treme neighborhood whose parents were recently arrested for selling drugs. She’s too young to join the program, but Durham will give her a pass.

“I’d rather get her out of that house at 2 and into our program so we can begin to intercede with all that negativity she sees on a daily basis, the stuff she considers normal,” he said. “These kids’ normal isn’t everyone else’s normal.”

Bradley Livers is one of the school’s successes. It wasn’t so long ago the 12-year-old was a troublemaker, many people who love him say. He didn’t listen, wouldn’t obey.

On an unseasonably cold Saturday morning, Bradley was tasked with supervising a group of younger kids. He kept an eye on them as they walked through the Treme neighborhood, making sure they waited until it was clear before crossing the street.

Wearing an overcoat, scarf and tweed flatcap, Durham trailed Bradley with another half dozen children in tow. Durham makes the trek every Saturday, rounding up children for the arts program at the church on Esplanade.

Bradley wasn’t so obedient when he joined the program, but now that he is behaving, Durham is giving him small leadership roles.

“Sometimes it’s tough for them to be put in that role, but they have to assume that role when we’re not there,” Durham said. “The adults haven’t stepped up and played their role. So many of the adults are drug users and dealers, so the kids look to peers for mentoring.”

As Durham collected three of the day’s students – one, 6-year-old Jakia Lee, proudly presenting him with her honor roll ribbon from school – Bradley began explaining how his neighborhood, Central City, “has so much killing.”

He didn’t leave his house for weeks, he said, after Keira Holmes Gordon was killed playing in a courtyard at the Calliope Projects in December.

Witnesses told police a man sprayed an assault rifle into the courtyard, injuring a 19-year-old and killing Keira just a few days before her 2nd birthday. A T-shirt depicting “God’s angel” is mounted on a wooden post adorned with teddy bears, flowers and crosses – a makeshift memorial there to remind passersby what happened.

Bradley said he is listening to his parents more often now. Asked why, he gives his take on Deuteronomy 5:16.

“The Bible says that if you don’t obey your mother and father, your life will be shorter,” he said.

The role race plays

Althea Phillips’ family has a wealth of ideas about why the lives of so many are cut short. Gathered in her living room to talk about the violence that took Phillips’ sons, about a dozen friends and family members say they believe race is an undeniable factor in the killings.

The plight of New Orleans’ young black men, they say, is so hopeless that they turn to crime. There are no jobs, there’s nothing to do after school – and it’s far too easy and cheap to get a gun.

That’s not the way it was when Phillips, 66, was growing up in the nearby Desire neighborhood. Back then, there were things to do.

There was a neighborhood youth center, a YMCA, drive-in theater, bowling alley, plenty of supermarkets and numerous after-school and social programs, Phillips said. A retired nanny, Phillips volunteered as a candy striper at a local hospital when she was young.

The city’s black communities began changing in the 1980s as oil companies, still among the city’s biggest employers, began consolidating operations and moving jobs out of New Orleans. At the same time, many black communities in the United States were witnessing the proliferation of crack cocaine.

Statistics show the murder count in New Orleans began climbing, from about 150 in 1985, to more than 250 in 1989, to almost 400 by 1993. Police say the murder rate has been seven to 10 times the national average for three decades. In the mid-1990s, tallying 300 to 400 murders a year was common.

Things became more dire a decade later as Katrina washed away what little there was left to do, and many poor communities struggled to rebuild. One of Phillips’ nephews said Katrina desensitized young people to death and violence, and there were few counseling opportunities available to help them cope.

Streets in certain communities still bear wounds from the day the levees broke.

In Zion City, the former First Greater St. James Baptist Church on Erato Street, with its doors wide open and most of its windows broken, serves as a play space for kids during the day, a crack house and bordello at night, neighbors say.

Down the street stands an ivy-laden home in danger of collapsing. A sign in the front yard warns the structure is toxic.

Bakersfield – 2,104Tampa – 2,107New Orleans – 2,593St. Louis – 6,205

In the once middle class New Orleans East and still-impoverished Lower 9th Ward, businesses and churches along major thoroughfares remain boarded up. A boat lies at North Dorgenois and Lamanche streets, and a Jet Ski sits under a graffiti-clad overpass less than a mile away.

On many streets in the Lower 9th Ward, scores of houses are empty and windowless. One house missing a large chunk of brick wall has been spray-painted in white: “Don’t Demolish.” Someone has written over the “Don’t” in green paint, adding instead, “Please.”

The contrast to the well-to-do Uptown, Garden District and French Quarter areas is not as stark as it was in 2006, when a tourism official called it a “tale of two cities.” Still, among the newly constructed houses, most of them on stilts, are myriad structures that are gutted and crumbling, their roofs and walls sinking inward.

Asked about the tale of two cities remark, Phillips’ nephew, Karl Washington, nodded seriously.

“Uptown was asking, ‘Can we get our trolley cars back?’ The Lower 9th Ward was asking, ‘Can we get some decent water?’ ” he said.

Three Samaritans killed, one recognized

Many statistics appear to support the Phillips’ assertion that race is a factor in the city’s poverty and violence.

The median household income, according to the Census Bureau, is almost half for black families what it is for white families. It’s also more than $4,000 a year lower than the national average.

A map of murders since 2008, which is linked out from the local newspaper’s website, shows a concentration of deadly violence in the largely African-American neighborhoods.

St. Charles Avenue forms a dividing line between the Uptown/Garden District area and young Bradley’s violent Central City neighborhood to the north. Though there have been more than a dozen murders in the French Quarter since 2008, the number pales in contrast to the spate of killing in neighborhoods just north of the Quarter, such as the 7th Ward, St. Roch, Florida and Desire.

While the disparities are unsettling to many in Phillips’ family, they say it’s the public response to three recent killings that drives their point home:

• Mike Ainsworth, 44, was killed earlier this year in front of his two sons while trying to stop a carjacking in Algiers Point.

• Joseph Elliott, 17, was trying to defuse an argument between his father and a neighbor when two men allegedly opened fire, killing the teen and his father in the foyer of their home in January.

• Elijah Grant, 23, was killed during a drive-by shooting a block from Phillips’ home. Witnesses told local media that when bullets started to fly, Grant leaned over 1-year-old Brittany Durcos and her two brothers, 7 and 8. All three kids were wounded but lived.

Ainsworth was dubbed a Good Samaritan, his killing reported as a tragedy in headlines across the nation. A $5,000 reward was announced for information leading to his killer – double the standard Crimestoppers reward.

Elliott and Grant received no such treatment, though community members say they acted just as heroically.

Ainsworth was white. Elliott and Grant were black. Suspects in Elliott’s killing were promptly arrested, but there was no special reward offered for help solving Grant’s murder. Police announced Tuesday they arrested a suspect, 17, in the Ainsworth killing, at a local high school.

Crimestoppers doubled the reward for Ainsworth after the organization learned he was killed while trying to protect a neighbor’s life, said executive director Darlene Cusanza. She said the organization was never made aware of the circumstances of Grant’s killing.

It takes a village – or a pizza

Elliott was a regular at the APEX Youth Center, said founder Lisa Fitzpatrick, and he fit right into the center’s mission. Known as “Joker” to his pals, he dubbed the self-administered weapons pat-down that the center requires “the hokey pokey,” making the serious exercise seem a little less grave for kids new to the center.

Elliott’s lighthearted demeanor helped him break down some of the barriers that divide New Orleans’ youth. Youngsters from Zion City and Parkway, for instance, have notoriously been rivals, but Elliott routinely quashed beefs between kids from the two neighborhoods.

Armed with many friends, Elliott would hear about percolating animosities between cliques and seek out the major players to find a solution to the disagreement, people who knew him said.

On a recent Saturday afternoon, several kids from the two neighborhoods were playing basketball together, something at least one Zion City native said was unthinkable a few years back. It isn’t solely because of Elliott’s efforts; APEX – which stands for Always Pursuing Excellence – has also done plenty to persuade youngsters to bury meaningless grievances.

Maybe the basketball courts or the cookouts helped. Perhaps it was the computer lab or TV room or air hockey or billiards tables or the scads of LEGOs. Maybe it’s that the kids know Fitzpatrick cares, that she holds church and dinner every Sunday at her home, that she’s putting together a GED program or that she’s looking for funding to build them a small recording studio.

Fitzpatrick doesn’t think it’s anything complicated. She’s seen barriers fall over a box of pizza.

“People ask, ‘How do you get kids down to the center?’ It’s not rocket science. Unlock your damned doors,” she said, “and a plate of cookies doesn’t hurt.”

There are rules at APEX, but Fitzpatrick lets the kids make them within her guidelines. She is tolerant about the content of music, except when it comes to the glorification of violence. She has even played Lil Wayne videos during church because she can find a lesson in anything.

Bakersfield – 17.3Tampa – 19.5New Orleans – 24.4St. Louis – 26

And though the kids’ pants sag below their buttocks, they’re wearing gym shorts beneath them. Fitzpatrick set the guideline – she didn’t want to see their underwear – and the kids came up with the rule.

“They can’t go out (in the street) looking like a choir boy, and I have to respect that,” she said.

Ask the kids at APEX why they came to the center, and they will say it’s because they were invited. One teen was smoking marijuana in the park when Fitzpatrick asked him to come visit. Others said they were playing football when she asked if they’d like something to drink.

“It’s safe,” said Keith Singleton, 18, wearing a black hoodie memorializing Elliott. “You’ve got something to do besides be on the streets, because when you’re bored, that’s when you get in trouble.”

Terry said he’d like to see more cooperation among the nonprofits and other groups that work with the city’s youth. He’d also like to see more commitments from residents, who he said are personally affected by the violence even if they don’t realize it.

To underscore the need for awareness, one of his deacons, Joyce Jackson, visits Serpas’ office every month carrying a rose for each murder victim. Serpas said the flowers serve as a reminder that the violence is “not acceptable.”

Everyone has something to give, Terry said, whether it’s their time or a $5 check, but the city and parents must also find more ways to get kids into the plethora of programs offered throughout New Orleans, no matter a program’s aim.

“What they learn is academic. Does it really matter in a crisis? What matters is if they’re not on the street, the street isn’t teaching them,” Terry said.

“And,” added Jackson, “they’re not on the murder board.”