Editor’s Note: David Frum, a CNN contributor, is a contributing editor at Newsweek and The Daily Beast. He was a special assistant to President George W. Bush from 2001 to 2002 and is the author of six books, including “Comeback: Conservatism That Can Win Again.”

Story highlights

David Frum: It's possible no candidate could reach delegate total to claim nomination

He says an open convention wouldn't follow historical pattern

Media spotlight and indepedent-minded delegates could sway the outcome, he says

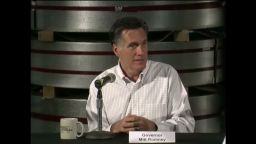

Frum says Mitt Romney might be forced to take positions unpopular in general election

As John Avlon has recently calculated, there is a real possibility that the Republican primary process could fail to yield a majority winner.

What would happen then?

Journalists like to speculate about “brokered conventions”: the kind of conventions we had 50 and 100 years ago, where party bosses chose presidential nominees in smoke-filled rooms. But you can’t have a “brokered convention” in a system where there are no “brokers.”

Here’s an example of how the old system worked:

In 1952, most rank-and-file Republicans wanted to nominate Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio, the leader of the party’s conservative wing.

In the dozen or so primaries and caucuses held that year, Taft won nearly 2.8 million Republican votes, as compared with only 2 million for Dwight Eisenhower.

But about three-quarters of the states had neither primaries nor caucuses. Their delegates were chosen at state party conventions, and those delegates answered to powerful state officeholders, typically the state governor.

So when the GOP convened in Chicago in 1952, those powerful state officeholders could negotiate among themselves, confident that they controlled the delegate count from their state.

That’s how Eisenhower won in 1952. The two most powerful Republican governors in the country – Thomas Dewey of New York and Earl Warren of California – preferred Eisenhower, and so Eisenhower it was.

That’s not how it would happen today.

Modern governors do not control their state parties the way governors did in the 1950s. And today’s delegates won’t do as they are told.

What would happen today?

Two possible scenarios:

1) Imagine that Romney falls just slightly short of the 1144 needed to nominate.

In this scenario, an individual party chairman from a smaller state with more old-fashioned rules might be lured to find some way to redirect his state’s votes to Romney. That is what happened in 1976, when Gerald Ford narrowly defeated Ronald Reagan by gaining the last-minute support of the Mississippi state delegation; that’s the most recent occasion when a convention chose a nominee.

The problem is that there are many fewer such old-fashioned states today than there were in 1976, with the result that the price such “available” states might be able to exact will be considerably higher than it was back then.

Ford only needed to replace his vice presidential candidate, dumping Nelson Rockefeller, anathema to party conservatives, in favor of Bob Dole, then a conservative hero.

But what price would be exacted from Romney? And what effect would that have on the election? Romney badly needs to pivot back to the center for the general election. Would a convention-season deal to get the votes of strongly conservative delegates veto that pivot and doom his hopes?

2) Imagine now that Romney falls substantially short of the 1144.

He might have won more votes and delegates than anybody else, but it becomes hard to argue that he is a clear favorite. Party insiders begin to murmur again about the need to find another candidate.

In an earlier era of American politics, that could be done. In 1920, a conclave of Republican Party bosses could bypass stronger candidates to choose Sen. Warren G. Harding, a politician whose main claim to fame was that he had kept on good terms with all party factions, and who would go on to win the presidency.

In 1940, Republican Party leaders chose a total outsider, Wendell Willkie, a businessman who had not only never been elected to anything, but who had actually been a Roosevelt delegate at the Democratic convention of 1932.

But now?

Who even are the Republican Party leaders – aside from Roger Ailes, that is? The big donors? But they already chose Romney and now find they cannot make their choice stick.

The big change in American politics over the past two decades has been the decline of followership. Party members expect the party to serve them – one major reason that both parties have drifted to the ideological extremes since the 1970s.

That expectation would only be intensified and concentrated in a party convention with Fox News and talk radio whipping and riling the delegates into angry emotionalism.

A decision-making convention in modern times won’t submit to the edicts of smoke-filled rooms. The delegates will want their own way.

If Romney fails to win the primaries over the next few months, brace yourself: not for a replay of 1920, when Republican bosses made their coldly calculated deal, but for a replay of 1896, when the Democratic Convention went wild for William Jennings Bryan after one thrilling speech. Of course, Bryan went on to lose in a landslide.

Follow CNN Opinion on Twitter

Join the conversation on Facebook

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of David Frum.