Editor’s Note: Nicolaus Mills teaches writing and literature at Sarah Lawrence College. He is at work on a memoir, “The Road to Mississippi.”

Story highlights

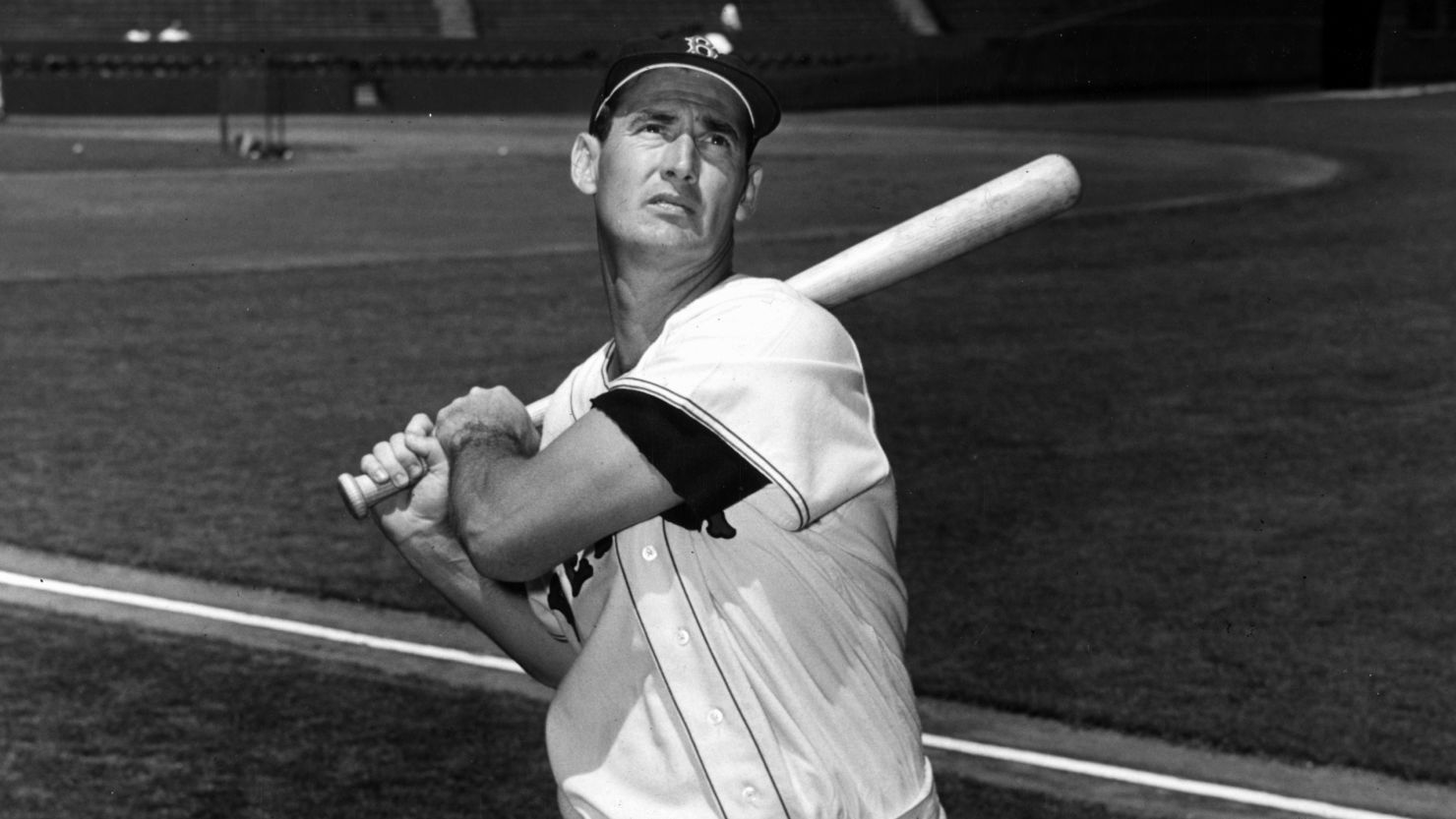

Nicolaus Mills: This year marks 70th anniversary of Ted Williams' .400 season

Mills says John Updike told lyrical story of Williams' final game

Williams hit a homerun in his last at bat, delighting a sparse crowd

Williams declined to acknowledge the cheers of the fans

It came as no surprise to anyone who is a baseball fan that last year on September 28 a flurry of articles marked the 50th anniversary of Ted Williams’ final game. Williams ended his career as few major leaguers do, with a home run in his final at bat.

But this year as we approach the 51st anniversary of the game that ended Williams’ career in 1960, it is time to turn our attention to novelist John Updike. It is the story Updike wrote for the New Yorker, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” that has allowed Williams’ last hurrah to take on a life of its own and that last year prompted critic Charles McGrath to argue that “Hub Fans” is “probably the most celebrated baseball essay ever.”

Thanks to Updike, Williams’ last home run is far better known than his even more remarkable feat – which took place exactly 70 years ago this month — of going six for eight on the final day of the 1941 season to lift his average to .406 and become the last man in baseball to hit .400.

Like Updike, I was at Williams’ final game. I cut the graduate school poetry class I normally went to three afternoons a week for the chance to see Williams end his career. I had expected to get stuck sitting in the center field bleachers, but Fenway Park was not even half filled.

Only 10,454 fans showed up for the game with the Baltimore Orioles. The Red Sox were a seventh-place ball club in 1960, and even for Ted Williams, most Bostonians were unwilling to take off work on a Wednesday afternoon so gloomy that in the sixth inning the stadium lights were turned on.

I got good seats along the third base line, and in the fifth inning I was able to move down to the field boxes next to the visitors’ dugout. The ushers could not have cared less.

Before the game Williams was honored with a Paul Revere silver bowl and speeches from Boston’s mayor and Red Sox television announcer Curt Gowdy, but the ceremonies felt perfunctory. Like the small Fenway Park crowd, they reflected Boston’s divided view of Ted Williams. He was someone to admire but not to love, and in his final game he stayed true to form.

In his last time at bat in an otherwise meaningless game, Williams pulled his miracle. In the eighth inning on the third pitch to him, he hit a towering home run to right field that cleared the Red Sox bullpen with plenty to spare. It was the 521st home run in a baseball career that had been interrupted by service as a Marine pilot during World War II and the Korean War.

The home run was the perfect stage exit, but as Williams trotted around the bases with his head down, he made no effort to dwell on the drama of the moment. Once in the Red Sox dugout, he refused to come out despite the chants of “We want Ted,” and when at the start of the ninth inning manager Mike Higgins sent Williams out to his left field position, then instantly replaced him, he jogged back to the Red Sox dugout with his eyes firmly on the ground.

As he had done since the end of his first year in the major leagues, Williams refused to tip his hat to the applauding fans.

The Ted Williams whom Updike describes is a man divided between pride in his craft and determination to avoid making himself vulnerable to the whims of fans. But what sets Williams apart in Updike’s account is that his internal and external struggles have taken place before thousands in stadiums across the country. In his role as a marquee athlete, he has not had privacy since his rookie year of 1939.

As much as our contemporary culture will allow, Ted Williams is a man of mythic dimensions,

In Updike’s story, ironically titled to sound as if it belonged on the sports page, Williams is both “Achilles, the hero of incomparable powers and beauty,” and a figure who at rest looks like “Donatello’s David.” But always he is larger than life. Circling the bases following his home run, Williams moves for Updike “like a feather caught in a vortex.”

Updike was able to capture more than any of us saw that afternoon at Fenway Park, and with the passage of time, his story of Ted Williams’ final game has become more powerful than the original experience.

Updike’s account is all that thousands who were never at Fenway Park that fall afternoon, and who now outnumber those of us there, know of the heights on which Williams left the game.

If Williams is our Achilles, then Updike is our Homer.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Nicolaus Mills.