Editor’s Note: James R. Acker is a distinguished teaching professor at the School of Criminal Justice at the University at Albany. He is the co-editor of several books addressing capital punishment issues, including “The Future of America’s Death Penalty: An Agenda for the Next Generation of Capital Punishment Research” (Carolina Academic Press 2009), and most recently “Wrongful Conviction: Law, Science, and Policy” (Carolina Academic Press 2011), co-edited with Allison D. Redlich.

Story highlights

James Acker: Debate question to Rick Perry about Texas' many executions drew cheers

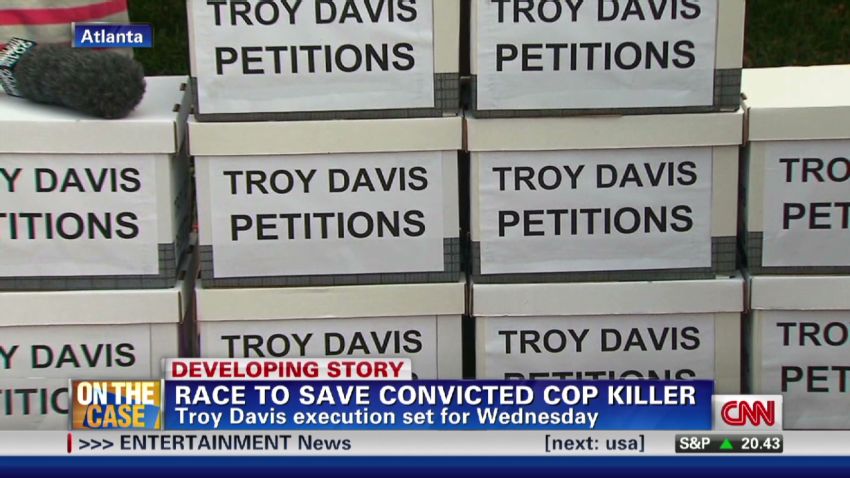

He says most people, though, are cheering triumph of justice, don't want wrongful executions

He says Troy Davis is condemned to die even though witnesses have recanted

Acker: Death penalty fraught with potential error; cases like Davis' focus our attention on this

The applause that erupted during last week’s NBC/Politico debate among Republican presidential hopefuls at the mention of the executions carried out during Rick Perry’s tenure as Texas’s governor cut off co-moderator Brian Williams’ question in midstream.

Williams: Gov. Perry, a question about Texas. Your state has executed 234 death row inmates, more than any other governor in modern times. Have you …

[SUSTAINED APPLAUSE]

… Have you struggled to sleep at night with the idea that any one of those might have been innocent?

The response presumably would have been more muted if Williams had been allowed to finish his question. Most people are less enthusiastic about the death penalty’s being applied against the innocent.

Following the question’s completion, Governor Perry volunteered that he has “never struggled with that at all,” explaining that “when someone commits the most heinous of crimes against our citizens, they get a fair hearing …”

Had the governor an opportunity to rephrase his answer, he likely would have clarified that fair hearings also are available to those who have been charged with but did not actually commit a heinous crime, and that such crimes might occasionally involve noncitizen victims as well. But the point is not to quibble about word choices; Texas governors can be forgiven linguistic mistakes if they allow no capital ones to happen.

Troy Davis, scheduled to be executed next week in Georgia for the murder of off-duty police officer Mark MacPhail, could be a capital error that is about to happen. Davis was convicted and sentenced to death more than 20 years ago by a jury that heard testimony from at least nine witnesses who implicated him in the killing. Since then, seven of the trial witnesses have recanted or revised their testimony so that it no longer points to Davis’ guilt. Of the two witnesses who have not revised their condemning trial testimony, one is believed by Davis’ supporters to have been the actual murderer.

The last judge to review the case concluded that Davis’ conviction and death sentence should not be disturbed, leaving the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles, which has previously declined to take action, as the last apparent barrier to Davis’ execution.

With no DNA or comparably reliable scientific evidence available to help confirm or contraindicate Davis’ guilt, the cry to achieve a final resolution of the case appears poised to trump the trial’s lingering uncertainties.

Davis may or may not be innocent. To acknowledge this much would suggest that he should not be executed. Yet Georgia is ready to move forward. If it is true that justice delayed is justice denied, it must also be true that an injustice not delayed is justice denied. (In another case, yesterday The U.S. Supreme Court delayed the scheduled execution of an inmate on death row in Texas after questions arose about a psychologist who had testified that blacks and Hispanics were more likely to commit future crimes.)

To make these observations about the cheering that greeted Perry’s execution record and the angst accompanying Troy Davis’ scheduled execution is to dwell on symptoms at the expense of their origins and deeper meaning.

I want to believe, and I do believe, that few of those celebrating at the mention of the Texas executions would not shed their festive enthusiasm and become reflective, sober, perhaps even somber if enlisted as witnesses to the execution of a fellow human being, even one indisputably guilty of committing murder.

I believe that those who cheer are applauding not the ugly reality of death inflicted by lethal injection but rather what it is that the punishment of death symbolizes: the triumph of law over criminal violence, of good over evil, the emphatic denunciation of unspeakably immoral misconduct, the restoration of order and a salve against the fear created in murder’s wake.

The reality of the death penalty is that even if it is politically popular (to wit, the Perry applause) it is an ineffective criminal justice policy, rarely employed, unevenly distributed and fraught with the potential for error. Its mistakes, unlike those committed in cases resulting in imprisonment, cannot be corrected. Capital punishment is infinitely more soothing and reassuring as an abstract symbol of justice than it is in practice.

Being under penalty of death is likely to be Troy Davis’ best reason to harbor hope for salvation. If he is innocent, he should not be in prison, let alone facing execution. Little focuses our attention as much as the prospect of an innocent person being put to death.

If Davis were not confronting execution, but instead had been convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole by his trial jury, the simple truth is that he would be just another nameless, faceless prisoner among the thousands upon thousands who have been convicted of crimes and incarcerated notwithstanding colorable claims of innocence.

Don’t get me wrong.

If Troy Davis is innocent, if there are real doubts about his guilt, then doing something, anything, to spare him from execution is of the highest order of importance. But if wrongful convictions occur in cases that result in the death penalty, as they undoubtedly do, then they occur exponentially more often and for all of the same reasons in the untold number of cases not resulting in the death penalty – ones that are met with a collective yawn or shrug of the shoulders by policymakers who are in a position to make meaningful systemic reforms.

Odd as it may be, the existence of capital punishment represents the most hopeful stimulus for procedural and substantive changes necessary to prevent and correct the injustices worked by wrongful convictions in criminal cases throughout the land.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of James R. Acker.