Madagascar is a biodiversity hotspot unlike any other.

The fourth largest island in the world broke off from mainland Africa around 150 million years ago, cast adrift in the Indian Ocean.

Isolation proved fertile breeding ground for evolution. Today the island has 8,000 species that are not found in the wild anywhere else on the planet.

Of these, lemurs are the star attraction.

There are 106 known species and subspecies of the molten-eyed furry forest primates, and tracking them is a thrilling adventure through a landscape of vast contrasts and changing climates.

Lemurs inhabit lush tropical rainforests, spiny dry forests, semi-arid desert canyons and cool central highlands.

Tracking them is the experience of a lifetime, but isn’t for the fainthearted.

And it’s become increasingly tricky as the lemurs face terrible threats to their existence.

Brink of extinction

Lemurs are thought to be the most threatened mammal group in the world, with most species facing extinction.

Although they’re ingrained in Malagasy culture, revered as the spirits of ancestors (their name translates as “specter”), efforts on the island to safeguard their future have been patchy.

Political instability hasn’t helped. A coup in 2009 plunged the country into instability and abject poverty, particularly affecting remote rural regions.

Tourism numbers, previously rising, plummeted and never recovered, resulting in the loss of funds for lemur conservation projects.

Their habitat’s also under threat with only 20% remaining, says Jonah Ratsimbazafy, a leading primatologist and co-chair of Madagascar International Union for the Conservation of Nature Species Survival Commission.

“Lemurs are one fifth of the world’s primates and are the goose laying the golden egg for Madagascar. Tourists want to see them in their natural environment.”

He fears that if deforestation continues, in 25 years Madagascar’s forest and lemurs would be wiped out.

But there is hope.

After 93 lemur species were put on critical, endangered or vulnerable watch lists in 2013, conservation experts drew up a three-year emergency plan requiring $7.6 million.

Smooth elections in 2014 helped spur efforts to seek international help, meaning viable projects to help save the lemurs could soon receive financial backing.

“Since last year, the political landscape has shifted,” says Christoph Schwitzer, director of conservation for the Bristol Zoological Society and the IUCN Primate Specialist Group.

“A new president was elected with new democratic government. Most donors and international funders are back on board.”

Optimism is in the air for the first time in years. For Madagascar’s wildlife, it can’t come soon enough.

‘Haunting cries’

As I scour forests across the country, with local guides, I’m spellbound by the haunting lemur cry echoing like a dawn chorus through the rainforest.

We watch as a family of indri, the largest living lemur, swings tree-to-tree deep in the Andasibe-Mantadia national park.

Seeing them in their environment is deeply moving – not least because they’re among the most at risk.

“Indri are being hunted for food by rural Malagasy needing to feed their starving families,” Schwitzer says.

“Lemur hunting rose after the 2009 political crisis and is directly poverty-driven.”

Some species are teetering right on the brink. The northern sportive lemur is believed to be down to just 60 animals.

Agriculture plays its part. Malagasy farmers have long employed slash-and-burn techniques, clearing trees to plant rice fields, burning the land to create fertile soil.

Then there’s illegal mining and the logging of precious rosewood and ebony – a lucrative operation run by heavily armed loggers known as the “rosewood mafia” that has depleted eastern rainforests.

Efforts to block the loggers through legal channels have previously been thwarted, but with an international task force now investigating exports, change seems imminent.

Success story

In recent years, Madagascar’s area of protected forest has tripled, although with no physical barriers or armed rangers, it’s been left to local communities to take action.

Anja Reserve, in the center of the island, is the biggest success story.

In 2001, it was designated protected land and the government transferred its management to the local community.

With the help of conservation and charity groups, the reserve has expanded, offering locals alternative incomes such as rice fields and fish farming.

It’s now the most visited private reserve in the country.

But reserves such as Anja are few and far between, says Haja Rasambainarivo, co- founder of Madagascar’s Asisten Travel Agency.

“Anja is on a tourist route. We need better infrastructure, better roads and a more reliable domestic airline to create more tourist routes through the country, to support more similar projects.

“Tourism can do this. It can bring infrastructure, education and jobs.”

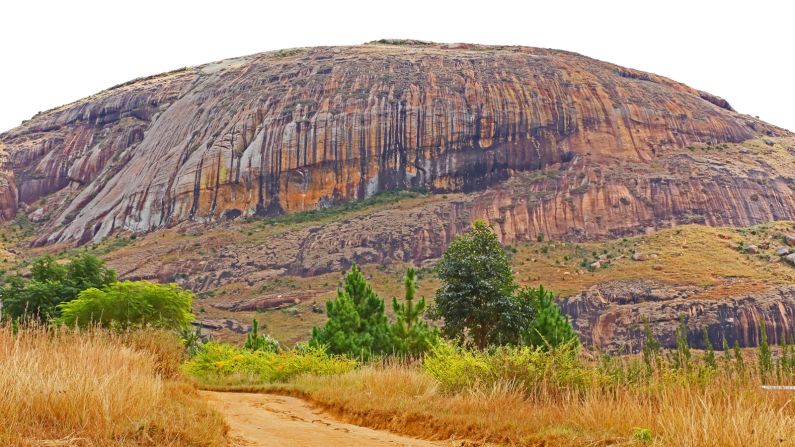

Anja Reserve is where I first see the iconic ring-tailed lemurs. The reserve is impressive with staggering granitic boulders and green valleys.

Hiking with trackers from the community association, their sense of pride is evident.

Officials say tourism is now a real priority for Madagascar’s government, which has drastically increased funding to promote the island as an eco-tourism destination and attract up to two million annual visitors by 2020.

Experts are now optimistic that lemurs have a future.

“I see hope in the upcoming breed of Malagasy conservationists,” says Schwitzer. “They’ve been internationally trained and are fully committed. It’s only a matter of time,”

Rasambainarivo adds: “Tourism can save Madagascar and, if prioritized, could save lemurs, wildlife and human life.”

If lemur survival is achieved, Madagascar could become the world-class ecotourism destination that it truly deserves to be.

Anisha Shah is a journalist and photographer, specializing in emerging destinations travel, from Mozambique to Myanmar. After six years as a BBC radio and TV journalist, she is now freelance and has been published across media outlets including CNN, Africa Geographic and Huffington Post. Tweet her @anishahbbc