The scenes could scarcely look more mundane: young South Koreans, disinterested by the camera’s presence, shop for groceries or sit by the pool.

But, faced with injustice around them, bearing witness to lives lived with resilient normality can be a radical act, says curator Antwaun Sargent, pointing to the photographs by Gowun Lee, part of a new group exhibition at Aperture, the New York photography gallery.

“What you see in these images is a shift in society.”

Lee’s subjects are queer – an umbrella term for sexual and gender identities that are not heterosexual or cisgender – their sexual identity resulting in many facing discrimination, violence, or cultural erasure in South Korea, where conservative attitudes to gender and sexuality prevail. But her simple images contain within them a statement of resistance, says Sargent: we’re here and not going anywhere.

“That’s a call – embedded in those images – for a society to do more, to be more open, to be more tolerant,” he says. “To really understand the plight of queer people and to make changes that make that a more prideful society.”

Shifting social attitudes

The exhibition, titled “The way we live now,” is made up 18 photographers and artists, whose images document shifting social attitudes and the overlapping battles over the truths we live by in this moment of social and political change.

As the USA and many countries around the world finds themselves embroiled in conflicts over rampant inequality, reactionary right-wing politics, and escalating nationalism, the show aims to present a rising generation resisting the simple divisions of the past.

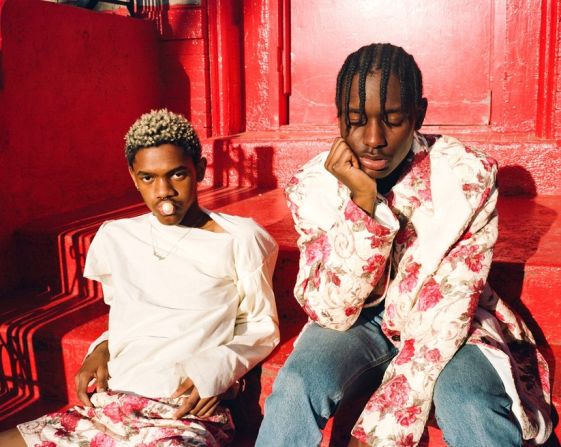

Amid the madness of daily news, there are new truths emerging, shared among a generation who are less divided than ever by national borders and more connected online: an openness to diverse sexual identities, a compassionate understanding of drugs and addiction, and an opposition to mass incarceration.

Selected from over one thousand submissions received after an open call by organizers Aperture, the exhibition includes photographers from across the globe, addressing intersecting issues including race, sexuality, mental health, government oppression, and resistance.

Different generations

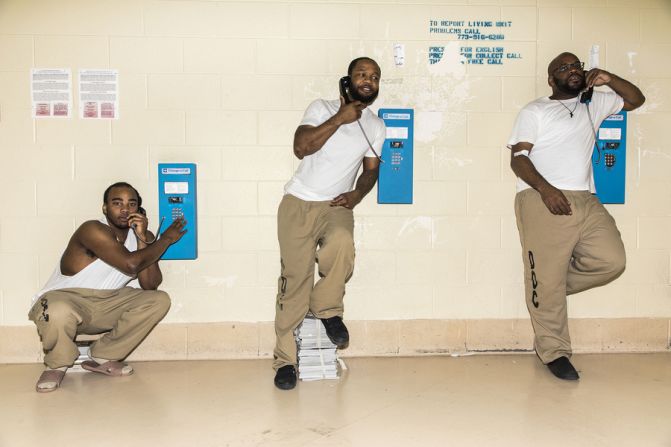

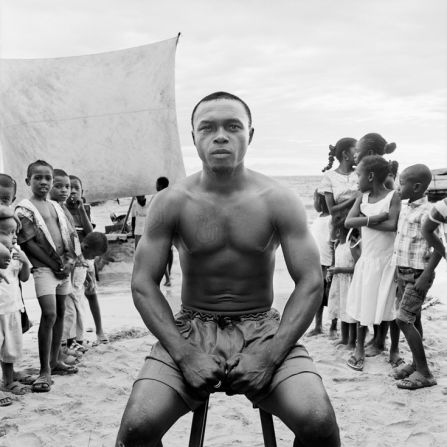

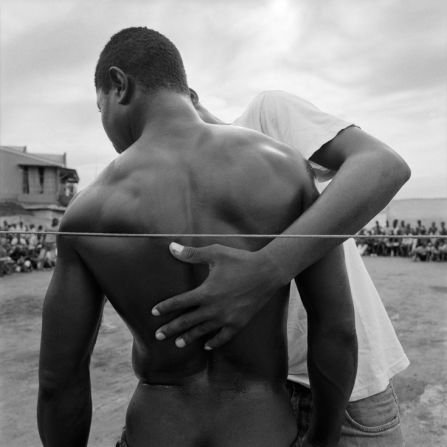

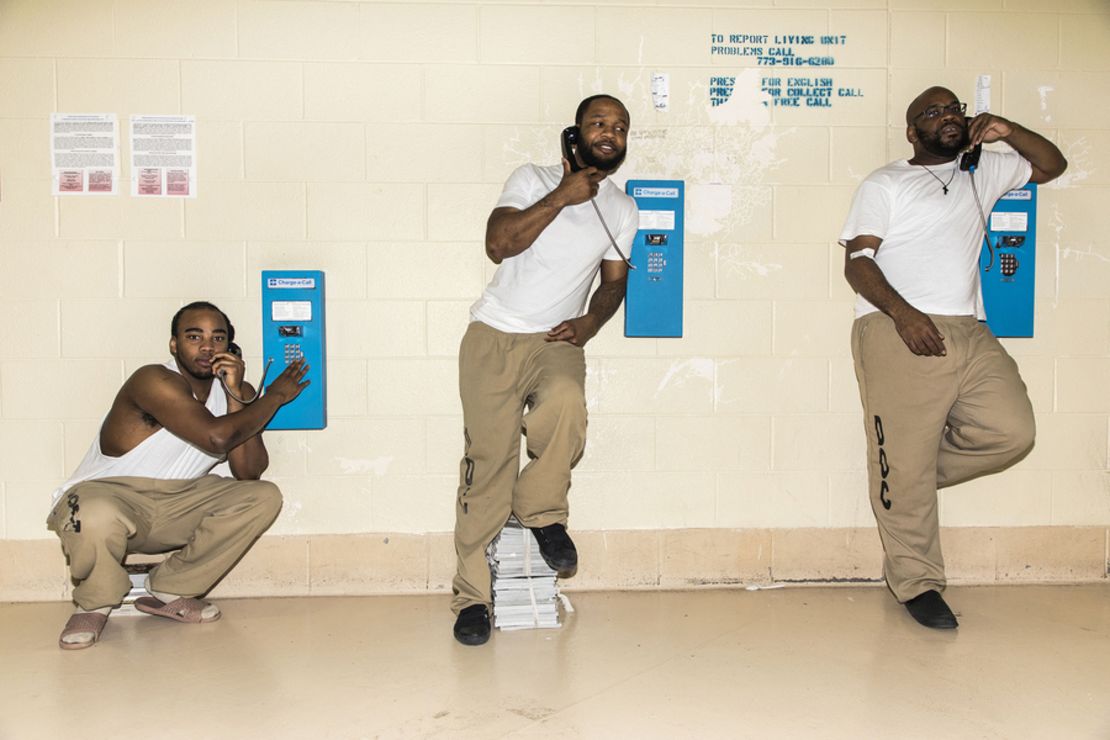

The Bubblegum Collective capture South Africa, 14 years after the end of Apartheid, through portraits of young artists, designers, and activists. Lili Kobielski documents Cook County Jail in Chicago, a jail that has become one of the state’s biggest mental healthcare providers. Diego Camposeco documents Latin American communities in American South, creating a rich picture of a community who have little voice.

Sargent says he has enjoyed participating in the conversations between people of different generations that the exhibition has brought to the fore.

He took a friend’s mother in her late 50s to see the photographs by Camilia Falcao that show transgender women at various stages in the process of transition.

“For her, where trans-ness is a relatively new concept, she’s trying to go: ‘is this a man or is this a woman?’” says Sargent.

“What she was doing was not being ignorant, she was looking for the traditional marker of what constitutes a female, a woman. And so I said to her that the very nature of that project is that sexual identity, gender, for our generation has not been something that is tethered to a body part.”

“That’s a totally radically different definition of what it means to be a woman, that what previous generations would have had.”

Bucking tradition

The way we live now – which takes its name from a bitter satire of a corrupt political establishment by Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope – pre-empts these kind of inter-generational conversations.

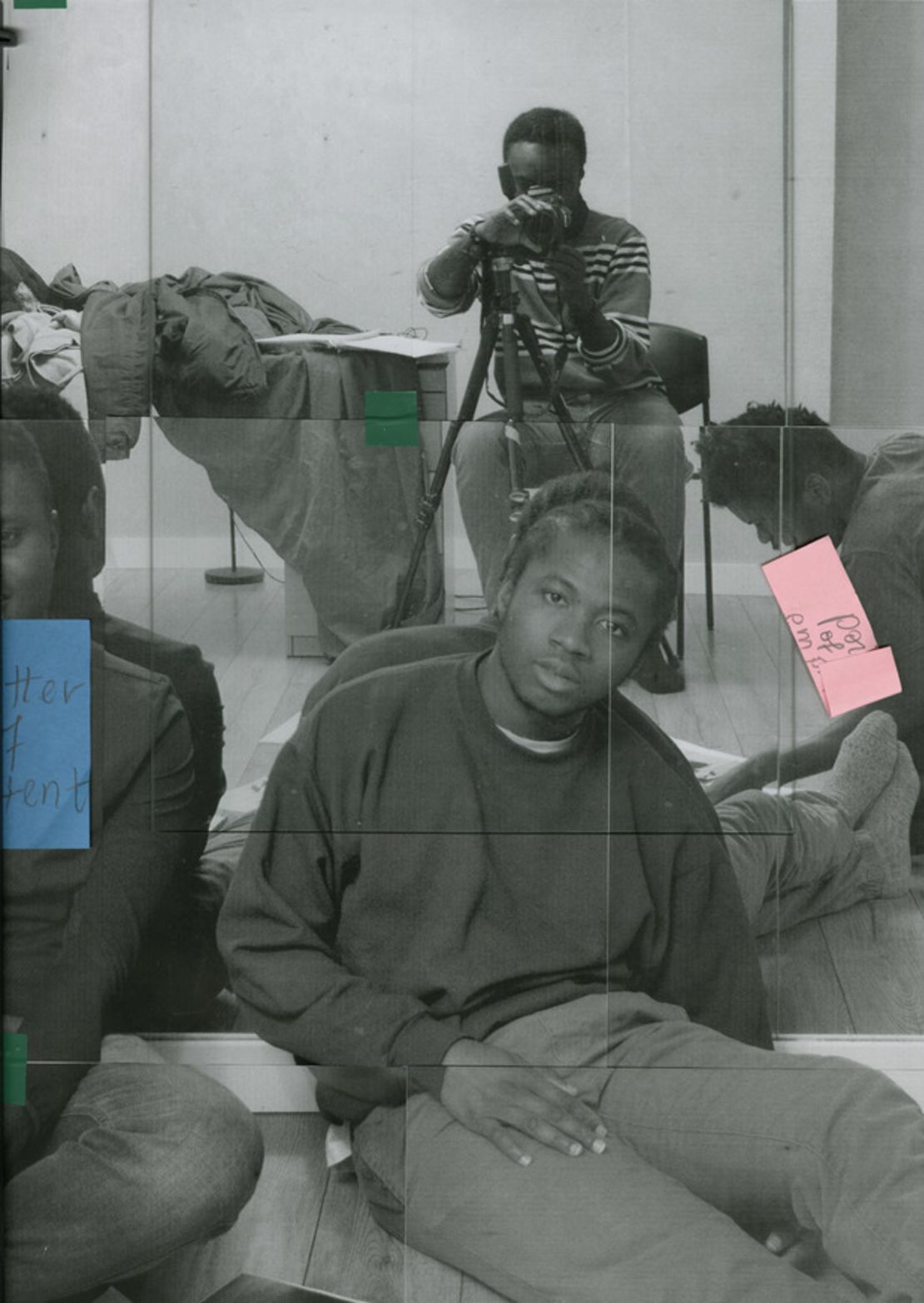

By working within the style and photographic traditions of the 20th century, they can question the certainties that underlie much documentary photography of previous generations, says Sargent.

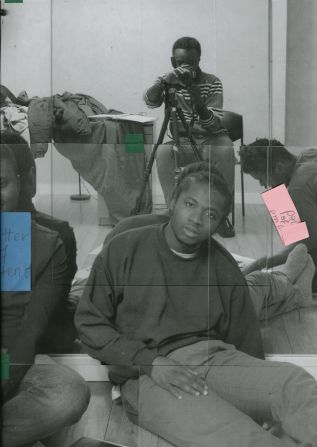

Like Luther Konadu, a Canadian photographer who composes shots of young friends sitting round the table to resemble the photography of Carrie Mae Weems. Konadu uses the same framing but wants to provoke viewers to question how stories are created by Weems and by any photographer.

“There is, in some ways, this ‘bucking’ of tradition and doing thing differently,” says Sargent

Most direct is Jonathan Gardenhire, an artist based in New York, whose images question the knowledge handed down from previous generations.

His photographs include within them classic books, such as the historically acclaimed 1986 “Black Book”, a collection of images of African American men, whose author – white photographer Robert Mapplethorpe – has more recently been criticized for “exoticizing” his black subjects.

“What he’s asking is: ‘What have we done with this knowledge?’ This knowledge that has been put into the cannon and revered and cited, over and over and over again,” says Sargent.

As many of the photographers in the show ask, more or less directly, which of the truths of the past do we keep and which to we throw away?

The 2018 Aperture Summer Open, The way we live now, is on at Aperture Foundation in New York through Aug. 16, 2018.