Todd and Jeff Delmay know how to fight for the things they cherish most: the right to marry one another and the ability to grow their family.

Now the couple, who were one of the first same sex couples to be legally married in 2015 in Florida, face another challenge, in the form of HB 1557, or the “Parental Rights in Education” bill, signed into law Monday by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis.

Todd is running for Florida House District 100 and Jeff is the co-chair of Equality Florida, one of the organizations that sued this week in federal court to block the law’s implementation. The couple were plaintiffs in Equality Florida’s lawsuit to secure marriage equality in 2014 in Florida.

Dubbed by opponents as the “Don’t Say Gay” law, it says that “classroom instruction by school personnel or third parties on sexual orientation or gender identity may not occur in kindergarten through grade 3 or in a manner that is not age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.”

Supporters of the bill say it’s needed so parents can have more oversight over what their students are learning at school and believe LGBTQ-related topics should be left for families to discuss at home.

Opponents say it would negatively impact an already marginalized community. They point to data showing that LGBTQ youth reported lower rates of attempting suicide when they had access to LGBTQ-affirming spaces.

“It’s the life we imagine for ourselves – being able to grow up, marry and have a child – and we’ve been able to have that and we’re showing kids the example that you can have a life like that or any life that you choose,” Todd Delmay told CNN. “But we have to be willing to allow them to see that from the youngest ages, just like we allow them to imagine being a firefighter or a doctor.”

The Delmays aren’t the only ones with such concerns. Middle school teacher Meghan Mayer worries about the conversations she won’t be able to have with her students. CJ Walden, a high school senior, fears his peers will be forced “back into the closet,” And Kim Hilton, a professor, believes schools may travel back in time and LGBTQ educators will be far and few.

The bill is scheduled to take effect in July and comes as conservatives nationwide are pushing for and passing bills that critics say would further marginalize members of the LGBTQ community and limit support from their allies in the classroom.

On Thursday, two LGBTQ rights advocacy groups, students, parents and a teacher in Florida filed a federal lawsuit challenging the state’s new law, making it the first legal challenge in motion to block the bill’s implementation and enforcement.

The lawsuit calls the Parental Rights in Education bill an “unlawful attempt to stigmatize, silence and erase LGBTQ people in Florida’s public schools.”

Many unanswered questions

The Delmays live a life with their 12-year-old son Blake that’s no different than a lot of other families, they say. They get him ready for school, take him to birthday parties, make sure his homework is done.

“I think there’s a very specific idea that people have in their minds of what it means to be LGBTQ,” Todd said. “And when I think about our lifestyle … it’s pretty much like a lot of other parents.”

Blake just celebrated a birthday in the classroom with Jeff and Todd present. With the new bill, Jeff worries whether he and Todd will be allowed to participate in school events. He thinks their presence as a couple may create a “weird energy” for teachers and leave Blake’s peers with questions that educators won’t be able to fully answer.

“To me, those little moments that are so sweet and so normal and so part of our everyday lives … there’ll be a little anxiety around it unnecessarily,” Jeff said.

“We’ve been amongst children who know Blake and once they know that Blake has two dads and you kind of explain to them the situation, they’re fine with it,” he said. ” … They just know Blake has two dads and his dads love him and he has two loving parents and that’s it. That’s all they needed to know.”

‘When you deny one kid, you’re denying all kids’

If Kim Hilton had visible gay women in her childhood or a safe teacher in her school growing up, the professor told CNN she would have understood her sexuality at a much younger age and “without a doubt” not have married a man.

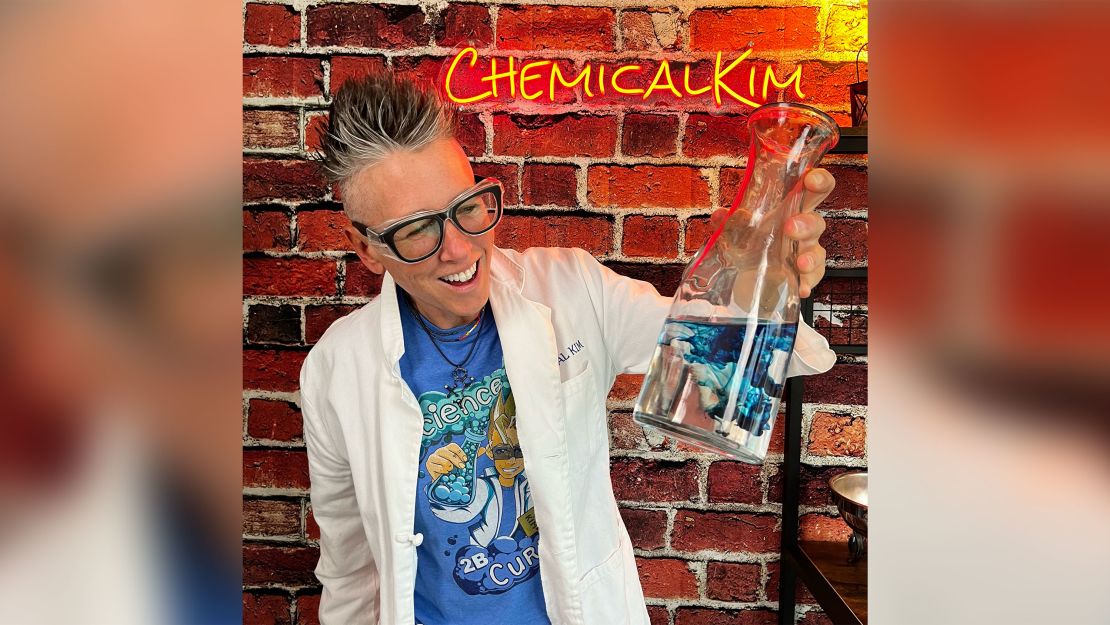

Hilton, who identifies as queer, grew up in a Catholic community; her children attended Catholic schools and she taught at a Catholic high school. She now teaches beginning level chemistry classes at Florida SouthWestern State College’s Collier Campus.

After her divorce, Hilton said six Catholic students at her children’s school, who identify as gay, reached out to her for support.

“They felt safe to come to me and talk to me about it,” she said. “But I was the only one and that made me sad and that’s why I’m getting very scared about this Florida bill, because we’re going to lower that population of visible LGBTQ educators,” she said.

“And I know that bill doesn’t say that but we all know, we can’t be that ignorant to that … it’s going to scare educators to try and hide their identity, or do the best they can to hide their identity and it’s going to be most damaging to those students,” she added. “I know it firsthand, because I saw it in the community I lived in.”

Through her TikTok videos, where Hilton is known as “Chemical Kim,” she said she’s been able to connect with young people around the world who have told her that they feel seen and validated through her presence.

Meghan Mayer, a middle school reading teacher in Sarasota, began her teaching career seven years ago. She said she works hard to let her students, particularly her LGBTQ+ students, know that she’s their ally.

“I’m straight. I’ve never gone through what my LGBTQ+ students have, but I know that they’re at a higher risk of bullying, they are higher risk for suicide, and I can never imagine what they’re going through,” she said. “The only thing that I can do is just try to be someone on this campus who they know that I’m going to support them and be in their corner.”

The contents of the bill are vague, Mayer said, making it difficult to have any discussions about experiences her students are having.

“During lockdown, we were heroes, right? Like it was ‘Praise the teachers, they’re amazing, look at what they can do,’ and now it’s like they have to make a bill to make sure that they’re (teachers) not talking about things that they’re probably not talking about anyways,” Mayer said.

“I just think that it’s an attack not only on teachers, especially teachers who are LGBTQ+, but it is attack on our kids,” she said. “And you know, when you deny one kid, you’re denying all kids.”

‘Condemning the LGBTQ+ community to death’

Amari White, 15, was surprised to see all the support from peers at her high school in Largo a few weeks ago as they showed up during the lunch break to protest the bill.

White, who identifies as transfeminine, said that while her mom is supportive of her, she felt more comfortable being open about her identity at school. Now, she feels she’ll avoid talking about it altogether.

Gender identity and sexual orientation are two different concepts, and the issue arises when people can’t understand the differences, White said.

“People think about it too much as like a sexual intimate feeling,” she said, “Rather than just understand that it’s just an attribute of a person … this person prefers boys over girls, this person uses she/her pronouns … I don’t think people can look at it that simple and they’re trying to erase it because they think it’s a lot more than just that.”

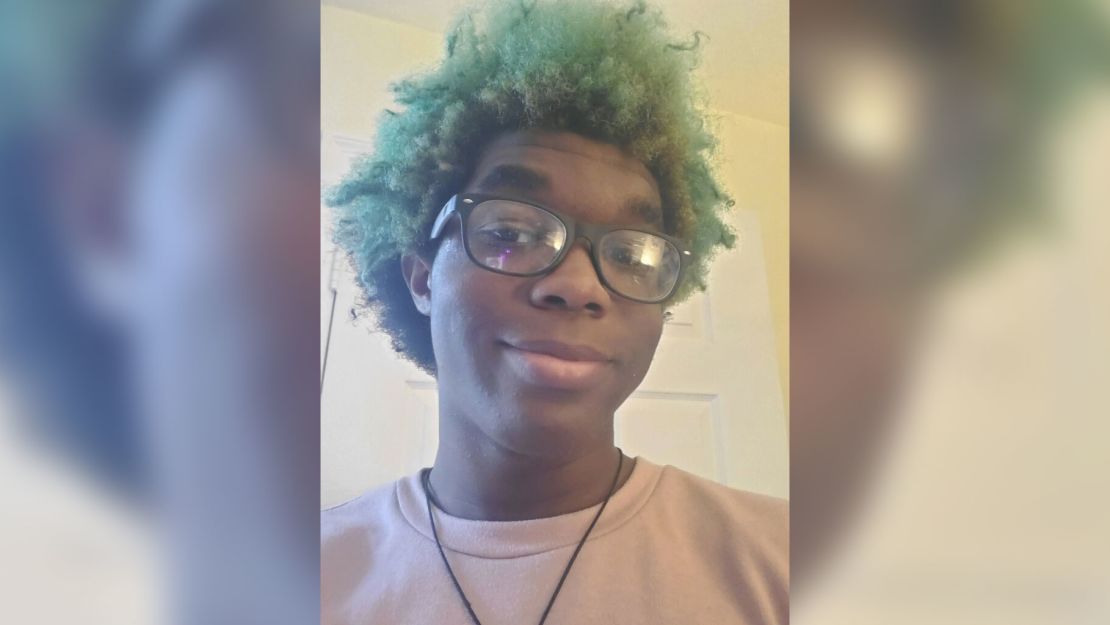

CJ Walden, a high school senior in Boca Raton, said that when he first heard about the bill he was “baffled.” So when the opportunity to testify in front of the Florida Senate knocked on his door, he was prepared.

Walden, who identifies as gay, said he came out officially in the eighth grade and was met with endless bullying and harassment. It has not wavered since, he said.

While Walden has a supportive family, he worries for his peers who may choose to “step back in the closet if they are wanting to continue to hide who they area,” he said.

“This bill is condemning the LGBTQ+ community to death,” Walden said. “If you’re telling a child that is gay or whatever sexuality, that they’re going to hell, or that they need to be quiet and not share with the class, that’s just going to cause so much inner trauma and conflict and if they don’t have a support system to turn to … what do you think is going to happen with this child?”

“They’re either going to pretend to be someone that they’re not or they’re going to go through depression and anxiety and even possible self-harm and suicide attempts,” he said.

It’s estimated that at least one LGBTQ youth between the ages of 13 and 24 attempts suicide every 45 seconds in the United States, according to The Trevor Project, a suicide prevention and crisis intervention group for LGBTQ youth.

“I don’t know that the fight will completely be won by the end of our lives,” Todd Delmay said. “The inspiration that the next generation is giving us that our son and other youth that will take on that fight … if we show them how it’s done and that you never give up, I think they’ll make it.”

CNN’S Devan Cole, Tina Burnside and Veronica Stracqualursi contributed to this report.