The first masks arrived on the White House grounds in February by special order of the National Security Council, mobilizing early on to address the emerging threat of the coming coronavirus. Job One in their emergency response was to take personal precautions, preparing for the critical work at hand, multiple officials tell CNN.

But word that some NSC staffers were being told to wear masks quickly made its way back to the West Wing and it wasn’t long before a sharp dictum came down.

“If you have the whole West Wing running around wearing masks, it wasn’t a good look,” one administration official recalled of the directive that came down from senior staff and lawyers.

Months later, the virus has hit the epicenter of the White House. President Donald Trump, who has long insisted the country is rounding the corner on the virus and mocked Democratic rival Joe Biden for wearing a mask, announced early Friday that he and first lady Melania Trump had tested positive.

The West Wing had wanted to “portray confidence and make the public believe there was absolutely nothing to worry about,” the official, who spoke before the President’s diagnosis, said, revealing the image-conscious reason for the opposition to masks for the first time.

The directive opened a schism in the White House complex that would ultimately hinder its ability to contain the spread of the new virus they were now calling Covid-19. Interviews with more than a dozen current and former administration officials show how that fissure appeared and spread even as confirmed cases in the US began to grow.

The officials all requested anonymity either because they were not authorized to discuss the matter or because they were sharing private conversations with people currently in the administration. But they tell a consistent story of how White House attempts to deal with the virus were dogged by Trump’s fixation on one thing: optics.

The ensuing disaster has now claimed the lives of more than 200,000 Americans in what may be the most politicized health crisis of the modern presidency. The radical polarization that now grips the country traces back to the very first workplace where it really sank in, at the West Wing of the White House.

White House spokeswoman Sarah Matthews, addressing questions about this story, said that the President “took the virus seriously from the beginning, as evidenced by his administration taking early steps in January to protect the American people.” It was Democrats and the media, she says, who were obsessing at the time – “over the partisan and futile impeachment trial.”

But several key officials tell a consistent and different story, about image management and the trouble it caused in pandemic response from the very beginning.

“We lost so much time,” a former administration official said, looking back. “The whole thing was mind-blowing. This could have been so different.”

All about optics

From the outset, the President’s political advisers were clearly thinking about optics. Almost from the beginning of the pandemic, their strategy was to cast the US infection rate in as favorable a light as possible – by comparing it to the rate in China, where the virus was born and already spreading wildly, several officials said.

“The numbers mattered, from a political standpoint, because it just looks better,” one former official recalled.

Information concerning the virus first appeared in the President’s daily intelligence briefing on January 3, but officials said it wasn’t clear how closely he read the briefing. No immediate action was taken, they said.

On January 6, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a Level 1 travel notice for Wuhan, amid fears that the virus was spreading beyond its origin.

The first-known case of coronavirus in the US was confirmed on January 20, but in the weeks prior to that revelation, the administration’s China watchers had already been paying close attention to the evolving situation, and worried that proactive measures needed to be taken in order to ensure it never made its way to the US, several officials said.

Yet when it came to announcing a big step forward in Trump’s trade deal with China, a visit from Chinese government officials was deemed by the White House as far too important to let concerns over the virus get in the way.

Three people told CNN that none of the Chinese delegates who attended the January 15 signing ceremony were tested before their arrival at the White House, nor do they believe that the topic of coronavirus was broached with the visiting delegation.

More than 200 people were invited to the White House that day to witness the signing, including members of the Cabinet and American business leaders. The show went on, and coronavirus was an afterthought. Crammed into the East Room, maskless attendees sat elbow-to-elbow, cheering on what was viewed as a “historic” deal that could give Trump a boost in the polls come November.

Trump, in the days following, would praise Chinese President Xi Jinping for his efforts toward containing the virus – praise that often evolved into a personal victory lap over the conclusion of the partial trade deal. But in retrospect, some officials felt the celebration was too great a risk.

Trump “put his Cabinet in jeopardy, and the 200 American business leaders who were there that day,” said one former administration official briefed on discussions that took place that day. “The Chinese put us in danger by coming here. But the President never uses that line against them because he doesn’t want to impugn his precious Phase One accomplishment.”

At that same time, officials say the West Wing had its mind elsewhere. The Senate impeachment trial began just one day after the President’s White House trade ceremony, and his political team was already looking ahead to his reelection bid. They were mainly hoping to make it through the year without any unexpected crises.

But then, a few positive coronavirus cases were confirmed in the US toward late January. West Wing staff often told others in the administration that this was nothing to worry about, one former official said.

” ‘This isn’t a big deal,’ ” the official, who, like the others, was concerned about this policy while supportive of others said, recalling how colleagues discussed it.

” ‘America is lowest on the list of places. Look at all these other countries doing a bad job. We’re doing a great job in America. We’re safe. We’ve got the best doctors in the world. Our borders are secure,’ et cetera.”

In internal White House meetings, staffers were repeatedly being told that the virus had been “contained” because there were only 15 cases.

Roughly 300 tests were available at that point, one of the former officials with direct knowledge said. Quietly, some of them began to question whether that was enough to make an accurate assessment.

Skepticism at the NSC

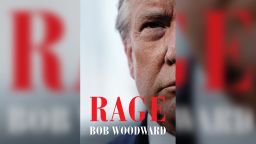

In a new book by Washington Post journalist Bob Woodward, Trump said that national security adviser Robert O’Brien told him during a January 28 task force meeting that “This will be the biggest national security threat you face in your presidency.”

Many National Security Council staffers had been consumed by mounting tensions with Iran following the killing of Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani. But officials said they gradually felt the pull to turn their focus. Covid-19 had now made its way across the planet, from China to the US, where at least half a dozen cases were confirmed before the end of the month.

In late January, when the first positive case to have been transmitted from person-to-person was confirmed in the US, several administration officials recalled hearing Ryan Tully, then the deputy senior director in the Weapons of Mass Destruction directorate at the NSC, warn colleagues that the rate of infection could “hit triple digits” by the end of that week. They heard him say that more needed to be done to contain its spread.

Another influential staffer was especially worried. Matt Pottinger had lived in China as a reporter for the Wall Street Journal before becoming head of the NSC’s Asia directorate, and, by now, deputy national security adviser. He was learning firsthand from contacts in Hong Kong about the aggressive contagious nature of the virus, several officials said.

“There were people in the room, many of them national security types, who also felt that proactive measures needed to be taken quickly because, ‘We want to reduce the risk as much as possible,’ ” a senior administration official said.

“There are the people, like the people within the WMD directorate, who wanted to go to great lengths for the sake of our national security, who saw this as a national security issue early on,” another former official said.

Within the NSC, managers took matters into their own hands. The health and national security advisers began to align in their pleas for more drastic measures, both globally and in-house.

As they advocated for more aggressive national policy, one unit – the WMD and Biodefense directorate – also ordered many of its employees to telework.

Pottinger moved his office from the West Wing to the adjacent Executive Office Building, where most NSC officials sit, in the interest of leadership continuity. He was hoping to avoid a scenario in which both he and O’Brien got infected (O’Brien later did test positive following a short family vacation). He warned of the need to protect NSC staff from the virus, especially because they need to work in secure facilities and thus shouldn’t telework, officials said.

In mid-February, CNN has learned that Pottinger emailed a Covid distribution list, which included O’Brien, about the effectiveness of mask-wearing. He pushed for guidance to go out to tell people to wear masks even weeks before the CDC or any other government agencies began advocating the public to do the same.

He was guided by the experience of South Korea and Japan, and the clear correlation between early mask-wearing and containment of a virus, given those countries’ experiences with Covid and earlier epidemics. Pottinger personally approached US allies to help supply personal protective equipment for White House staffers, a senior administration official said.

One now-former administration official recalled the day when the masks arrived, and they were told that wearing them was mandatory: “When those masks came in, we were all told to go pick up four masks from WMD (office) … So we went the first day and picked up our masks first thing in the morning.”

Shortly thereafter, though, someone told White House press about the mandate, and it wasn’t long before NSC lawyers told Pottinger he couldn’t require masks.

The decision by the White House not to take stringent protective measures put the West Wing’s senior officials against mid-level experts on the NSC, a difference of approach that would soon show up in policy making, as well.

Then-acting chief of staff Mick Mulvaney also felt the effort was undermining the confident image Trump was looking to portray, one person said.

“If you have the whole West Wing running around wearing masks, it wasn’t a good look when all they wanted to do at that point was portray confidence and make the public believe there was absolutely nothing to worry about,” that same person said.

Mulvaney didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Another former official said there was no one in the White House or NSC whose job was to coordinate among the Cabinet and various agencies to let them know what they needed to do. O’Brien, this person noted, wasn’t in any of the initial task force meetings.

“In theory,” the official said, “it’s his job.”

In a May interview, O’Brien pushed back on the idea that he’s been absent, saying he counsels the President regularly on the pandemic.

“We don’t believe we should be out front in the news,” he told CNN, adding that it is not his personal style to make a lot of news. “We want to give quiet advice.”

He added that he has deferred largely to Pottinger on coronavirus-related issues because of his China expertise.

Trump chooses route that looks best

The administration began taking precautions in late January and February by limiting travel to and from hard-hit regions of the world. Still, administration officials tell CNN that very little action was taken domestically, early on, to inform and protect Americans.

Despite the pleas of some of his closest advisers, the President heard only what he wanted to hear, not what he needed to hear, these people said.

Another person to sound alarms early on was China hawk Peter Navarro. Unlike Pottinger, who had the respect of his NSC colleagues and a strong command for the interagency processes involved in working at the NSC, Navarro, a bombastic and often oroversial character, had something far more valuable in the Trump era. He had the President’s ear.

Navarro typically had a flair for drama and would often rub colleagues the wrong way as a result. But his early warnings about the potential catastrophe posed by the virus didn’t completely fall on deaf ears. In a pair of memos on January 29 and February 23, Navarro painted a grim picture about the potential loss of life facing America as a result of the virus. He predicted “loss of life of as many as 1-2 million souls” in one memo sent to O’Brien and the Covid-19 task force and he called for an immediate travel ban on China.

The second memo zeroed in on a need for $3 billion in supplemental appropriations geared toward boosting the availability of personal protective equipment, vaccine development, testing and treatments.

One former administration official who received the emailed Navarro memos recalled “I remember reading that and thinking ‘what the f**k?’ On the one hand, we were tempted to dismiss it as just Peter-being-Peter. But it was pretty thorough and really scary.”

Another recalled the information in Navarro’s memos as “jarring,” and noted that it triggered a scramble in the West Wing. Mulvaney, this person said, felt that the memo broke with process. He wanted Navarro to be reined in because it was “completely contradictory” to what the White House had been saying.

Not only was it counter to White House messaging, this person noted, but Mulvaney also worried that Navarro’s remarks would run counter to White House efforts in late February to get $1.25 billion in emergency funding from Congress to deal with the coronavirus.

Navarro, Pottinger and others went against the prevailing view in pressing for such drastic measures, such as widespread travel bans – both domestic and abroad – as well as precautions to keep national security staff safe, because Trump himself wasn’t quite ready to embrace this as a full-blown crisis, multiple current and former officials said. The 2020 election was, at the time, about nine months away and the President didn’t want anything disrupting a year of boisterous rallies, political events and economic prosperity.

Still, the President listened. He announced restrictions on travel from China, which took effect February 2. It wasn’t a total ban, but the move suggested that Navarro and the NSC were rising in influence.

By then, the Chinese government had imposed lockdowns in parts of its own country. Tensions between the President’s medical and economic advisers came to a head, with medical experts – backed by the NSC – advocating for similar measures across the US to keep the country safe. But from February 24 to 28, stock markets across the globe reported their largest one-week declines since the 2008 financial crisis.

The President places as much importance on the health of the Dow Jones Industrial Average for validation of his job performance as he does with his polling numbers. But instead of accepting that the spreading virus was driving markets down, he instead pointed publicly to the oil war that was, at the time, brewing between Russia and Saudi Arabia.

Trump’s acquittal in the impeachment inquiry came earlier in February, and close advisers said he felt emboldened to tackle the election year without any other major distractions.

But when the President traveled to India in late February for a largely ceremonial visit, NSC officials were hunkered down planning their “switch to the doom and gloom messaging.” Several officials pointed to a clear turning point that came while Trump was abroad, when a doctor from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention went public calling for strong measures, including closing schools.

India was “the freak-out moment, internally,” as West Wing officials came to realize the virus is very real, and America is unprepared, recalled another official.

While the President was abroad, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, triggered a scramble at the NSC when she told reporters that local communities and cities may need to “modify, postpone or cancel mass gatherings.”

“Now is the time for businesses, hospitals, community schools, schools and everyday people to begin preparing,” she said in late February.

Once national security officials heard that, “we set out on a journey to look at the quantity of masks we have. What is the plan for hospitals to take on victims? What type of ventilators do we have? What other critical pieces of equipment did we need?” one person recalled, adding that what they found in their hunt was disconcerting.

“We found out pretty quickly that we could not find that information. We just couldn’t find it – mostly because it wasn’t good information. We had less masks than we probably needed. We didn’t have a plan for hospitals,” that official recalled.

Philip Ferro, the senior official in the WMD directorate, at that point began sounding alarms, telling officials on the President’s task force and anyone who would listen that their planning was too small scale, and that they needed to start gearing up for a shutdown of major US cities. He told everyone: “‘We knew this was gonna happen eventually. This is it. This is going to be really bad,’ ” that person said.

But the President wasn’t ready to hear it. When he returned from India in late February, he named Vice President Mike Pence as head of the task force. Pence’s staff was smaller and it took them several weeks to get up to speed on the efforts that had already been underway. The move “made us lose three weeks of planning” one official said.

The biggest problem, that official added, was that the White House couldn’t agree on strategies for mitigation – or even on the idea that it was necessary to do so.

The NSC didn’t address specific questions regarding Pottinger, Navarro, Tully or Ferro’s efforts to warn colleagues about the trouble ahead.

O’Brien, responding to questions for this story, said in a statement that Pence’s leadership “has been essential in responding to this deadly pandemic.”

He added that “the vice president played a pivotal role in mobilizing the entire federal government to meet this historic challenge.”

By mid-March, when the coronavirus death count was climbing toward 500 and about to take off like wildfire, the President’s image-consciousness was in full force. Ultimately, he sided with the staffers thinking most about optics, signaling his choice more than a week after the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic on March 11.

“This is going away,” he said. “We’re going to win the battle.”

This story has been updated Friday to reflect President Donald Trump’s positive coronavirus test.