By now, we’ve all heard this advice countless times: Wash your hands often and thoroughly, with soap and water.

It’s one of the best weapons in our arsenal right now against the coronavirus.

Though washing our hands seems painfully obvious now, it wasn’t always that way.

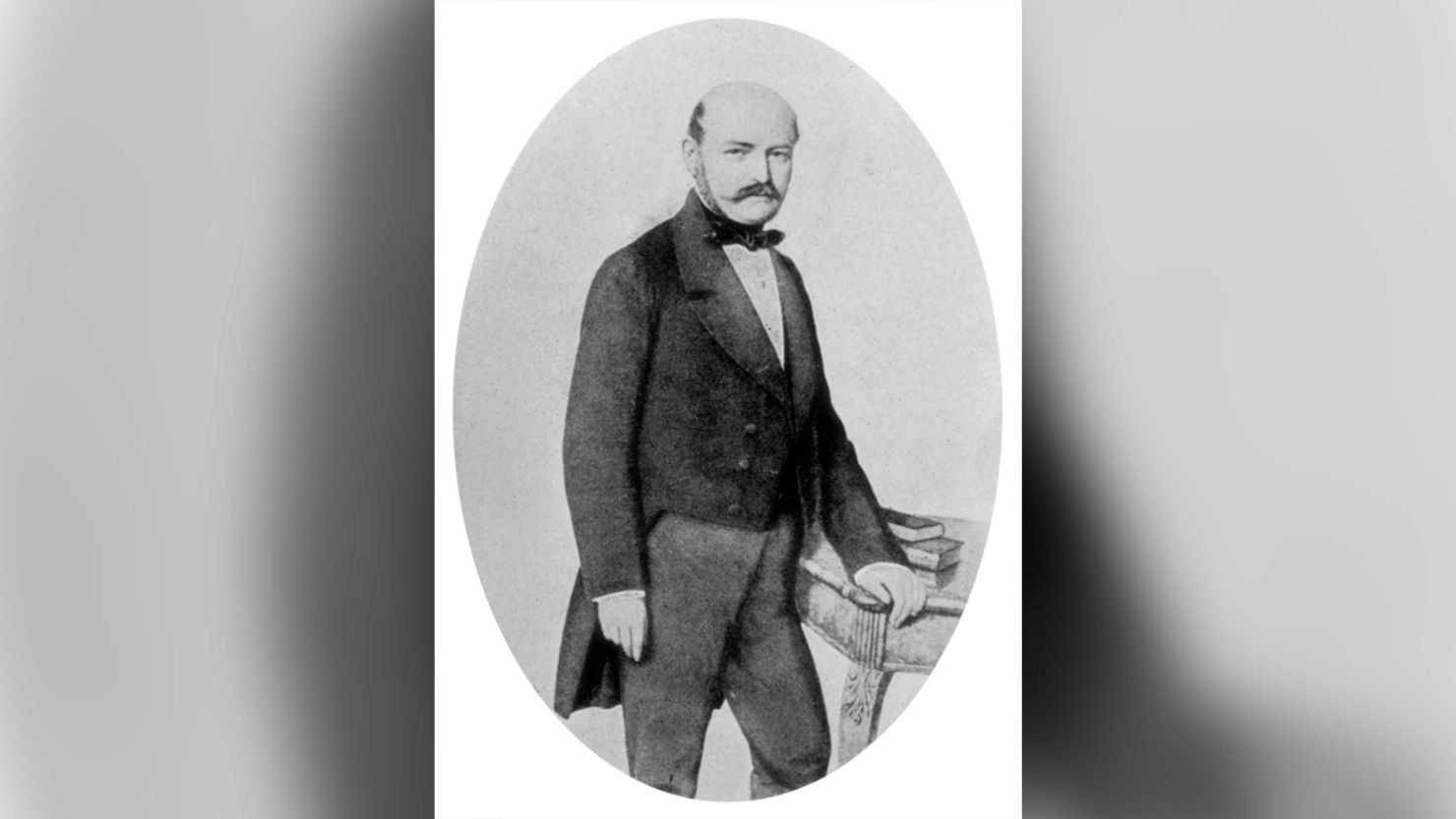

The importance of handwashing is thought to have been championed by Ignaz Semmelweis, a 19th century Hungarian obstetrician who worked in the maternity wards at the Vienna General Hospital.

Semmelweis’ story is detailed in a 2013 article by Dana Tulodziecki, a philosophy professor at Purdue University. He’s also the subject of Friday’s Google Doodle.

How he made the discovery

The Vienna General Hospital had two maternity divisions, one staffed by doctors and another staffed by midwives. Semmelweis, who worked in the one staffed by doctors in the 1840’s, noticed that new mothers were dying of a disease called childbed fever at higher rates in his division than they were in the one staffed by midwives.

So he set out to find out why.

Some people believed the disease was caused by things in the air, overcrowding or unhealthy diets. But those conditions were the same in both wards, so Semmelweis ruled out those possibilities.

Then he started conducting some experiments.

One theory was that the disease had something to do with the birthing position. Women in one clinic gave birth on their sides, while in the other, they gave birth on their backs. He had both clinics use the same birthing position, but that didn’t make a difference.

Another theory was that a priest who walked through the first ward ringing a bell might be causing psychological terror. But it turns out, that wasn’t it either.

Finally, Semmelweis had a breakthrough in 1847.

One of his colleagues was injured by a scalpel during an autopsy and ended up dying from an infection. Semmelweis hypothesized that pieces of cadavers had entered his colleague’s bloodstream and caused the infection that killed him. And because doctors who were performing autopsies then went over to the maternity wards to deliver babies, it was possible that new mothers were also being infected by pieces of dead bodies.

To test the hypothesis, Semmelweis required doctors to wash their hands after autopsies with chlorinated lime in between examinations. Eventually, mortality rates of mothers in the clinic where doctors worked fell to that of the one where the midwives worked.

Despite the results, some of Semmelweis’ peers viewed his theory with skepticism. According to Tulodziecki, Semmelweis maintained that a lack of handwashing was the only cause of childbed fever – something that his colleagues didn’t accept, given that there were other cases of childbed fever outside that hospital that couldn’t be explained in the same way.

But decades later, his ideas were credited with contributing to “germ theory” – the currently accepted medical theory that many diseases are caused by microorganisms.

And it’s why, today, we clearly understand the benefits of washing our hands.