While Boris Johnson is cheered by supporters for his tough talk on Brexit, people in Brussels are becoming increasingly unsure if the British Prime Minister really wants to strike a deal with the EU. And that’s the crucial question, because if he doesn’t, then there won’t be a deal.

Ireland’s leader, Leo Varadkar, said on Tuesday that Johnson has served up half of his predecessor’s Brexit plan and tried to present it as something new.

Talks are stuttering, as sources close to Johnson try to pin the blame for no deal being reached on the Europeans, and especially Ireland.

This doesn’t mean that Johnson is gunning for no deal, but that in negotiations, it takes two to tango. This was the lesson of former Senator George Mitchell, the US diplomat who corralled Northern Ireland’s politicians to peace in the 1998 Good Friday (or Belfast) Agreement.

The day after that deal was struck, he told me that getting the compromises needed for a deal came from convincing both sides that the deal they wanted was not only possible, but that the deadline to achieve it was immovable.

As Johnson struggles with Brexit negotiations and the Good Friday Agreement looks in jeopardy, the lessons Mitchell learned by achieving it could be an indication of what comes next in Brexit.

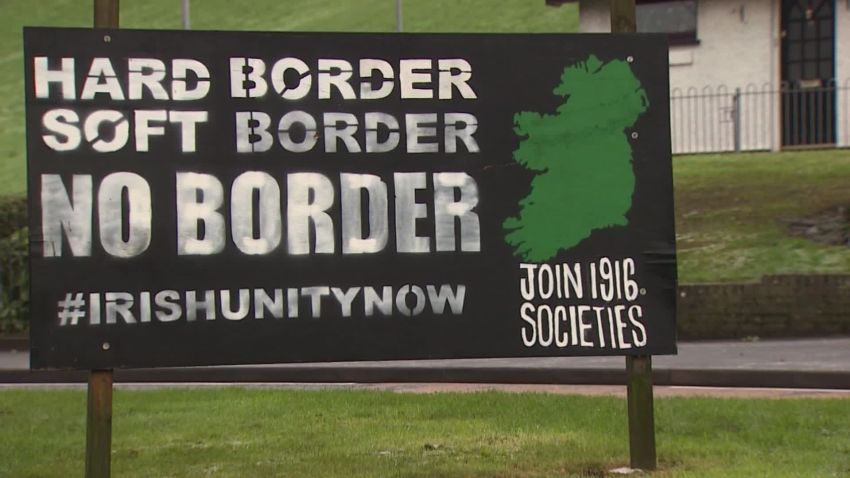

Johnson’s challenge in delivering Brexit has come down to the same friction Mitchell faced: managing the desires of both Northern Irish Unionists and Republicans.

However, where Mitchell was seen as an independent middleman, most believe Johnson is on the side of the Unionists.

Republicans, moderates and Northern Irish businesses deplore his Brexit plan, which would keep Northern Ireland in the EU Single Market, and at the same time out of its Customs Union.

It effectively installs a customs border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and a regulatory border between Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

Johnson’s Northern Irish allies, the Democratic Unionist Party, are taking heat from the Unionist moderates, the Ulster Unionist Party. Both parties would do well to remember the lessons of the Good Friday Agreement

The UUP, the biggest Unionist party at the time, signed up to it, while the DUP didn’t. Unionist voters punished the UUP, who have been in the political wilderness since.

In short, the place where Brexit talks are at their most combustible, Johnson’s troubles are most acute. Push compromise on any set of Northern Irish politicians and watch your plans backfire.

This means that Johnson’s room for maneuver will be extremely limited. The DUP told its voters two years ago they will leave the Single Market and the Customs Union with the rest of the UK.

Even with the fig leaf of consent on the Single Market, which is also part of Johnson’s Brexit plan, it’s not enough to hide their massive reversal. The DUP are voters’ party of last resort to keep Northern Ireland in the UK. Any border between the two risks looking like surrender.

But back to Senator Mitchell’s points: desire and belief. Desire for a deal and belief in the deadline.

Back in England, many voters who would never normally back Boris Johnson find his “do or die” threat to the EU is both admirable and effective.

Whether they feel that way in a few weeks or when a general election comes is another issue. But for now, polls suggest the UK believes that the Prime Minister has the right stuff. He has managed to whip up belief, both here in the UK and in Brussels, that there is a hard deadline for talks.

To do it, he is executing what appear to be almost impossible constitutional pirouettes.

Two weeks ago, the UK’s Supreme Court declared that the advice he gave the Queen to prorogue Parliament was unlawful. He disagreed and ignored opposition calls for his resignation.

On Friday, a Scottish court heard that he will follow through on the so-called Benn Act, which instructs the government to ask the EU for a three-month delay to Brexit.

Hours later, he tweeted: “New deal or No deal – but no delay. #GetBrexitDone #LeaveOct31”.

Less than three months in office Johnson, is still fresh. When Senator Mitchell sat with Northern Ireland’s leaders, they were war weary. Voters wanted peace.

Mitchell hoped the Easter holiday weekend would focus minds. He had set it months in advance to be the moment of truth when both sides would believe their final compromises had to be made.

I was there that night, April 9. 1998, outside the building. The hour before midnight and the deadline, the grass and ground stiffened with frost. Inside, positions hardened, the deadline passed, and Jeffrey Donaldson jumped ship from the UUP, who were on the cusp of compromise, to the perpetually inflexible DUP.

That night the DUP refused to compromise. Which is what makes their agreement with Johnson’s Brexit plan today all the more significant.

As the clock continued past midnight, the UUP’s David Trimble took a leap of faith that sealed the deal.

He would have to take the IRA at their word that they would “put their weapons beyond use.” There would be no surrender, no handover of guns, none of the symbolism a victor gets at the expense of the loser.

Mitchell had brought both sides to the point believing a deal was within grasp. In that moment, the thorniest of issues of 30 years of bloodshed could be reconciled.

There is a reason to repeat this point, because this is the moment Johnson insists he will have: come midnight on October 31, the clock will stop ticking and the UK will be out of the EU, deal or no deal.

But these do not sound like the words of a man committed to compromise.

That was not how Trimble faced his moment of truth. He believed a deal was within reach and that he, David Trimble, could make it happen.

He signed up to the peace deal. He won a Nobel Peace prize. He became Northern Ireland’s top politician. Yet within a few years, voters rejected him and his party, ending his political career and sending the UUP into the political wilderness.

Johnson hardly seems the type to willingly take on such a career suicide.

Indeed, Johnson appears to have convinced the EU leaders he insists the next compromise must come from Brussels.

All this will look mighty familiar to a diplomat as gifted as Senator George Mitchell. A deadline looming, the stakes huge, two sides far apart, a blame game emerging. What he might be struggling to see is a genuine belief, on either side, that a deal can be done.