Story highlights

Evidence of child sacrifice found in Turkey

Archaeologists say it could help us understand how people transitioned into urban civilization

Human remains have been found in Turkey, which are believed to show evidence of child sacrifice some 5,000 years ago in an area known an as “the cradle of civilization.”

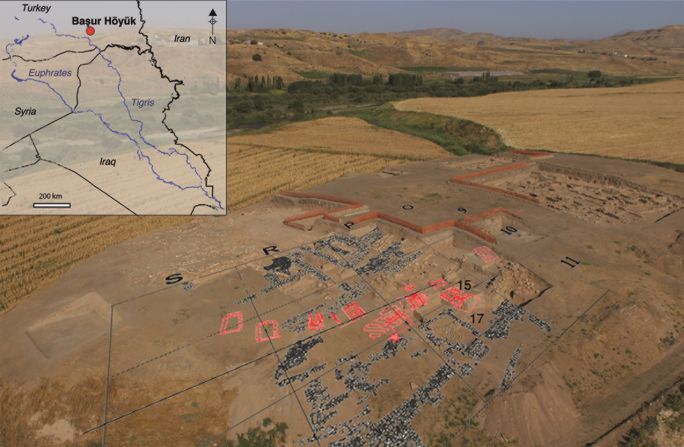

They were found in a grave that dates back to between 3100 and 2800 BC and was found at the Bronze Age Başur Höyük cemetery in southeastern Turkey. It is believed to be one of the earliest examples of human sacrifice in ancient Mesopotamia, the region where humanity developed its first complex urban centers.

Archaeologists say the find could potentially help them understand how people at the time transitioned into large early states and urban civilization.

A total of 10 skeletons, a mix of males and females aged between 11 and 20, were excavated from the site.

The grave consisted of an inner chamber, separated from an outer chamber by a stone door.

Read: FBI cracks the case of the 4,000-year-old mummy’s head

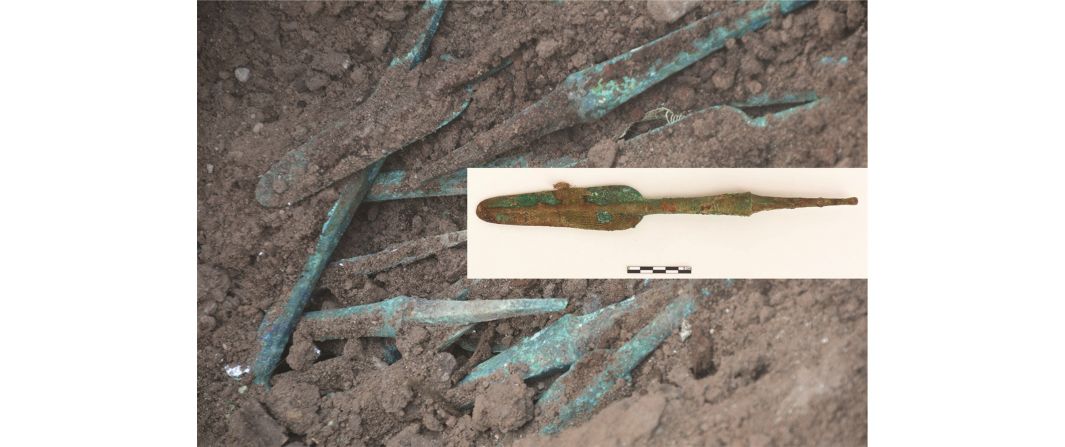

Eight of the skeletons were piled one on top of the other in the outer chamber. The skeletons of two other children were found in the inner chamber, surrounded by metal wealth such as bronze spearheads, suggesting their possible higher social status.

Brenna Hassett, a bioarchaeologist at London’s Natural History Museum, who co-authored the paper on the discovery, published last month in the “Antiquity” journal, led the analysis of the skeletons. She confirmed that two young adults found in the outer chamber suffered violent deaths, with sharp force traumas to the head and the hip socket.

Servants for the afterlife?

The manner of death and the fact that they were buried in the outer chamber are reasons to believe the eight bodies served as “retainer” sacrifices for the two in the inner chamber, according to Hassett.

The burial practice of providing sacrificed humans as retainers to another deceased person to attend to them in the afterlife is believed to have also been carried out in ancient Egypt.

“You wouldn’t bury people in that position if you weren’t trying to sort of reflect a type of social organization,” she tells CNN. “Their position in death may well reflect their position in life.”

It’s unclear yet how the rest of the children died, as well as who might have sacrificed the retainers. But the discovery is significant because the Başur Höyük cemetery dates back to a turbulent time when people were experimenting with coming together to form states and cities, according to Hassett.

Read: 11,000 years ago, our ancestors survived abrupt climate change

She added that before Mesopotamia – the area where most of modern day Iraq, eastern Syria, and southeastern Turkey are located – birthed developments such as agriculture, astronomy, and mathematics, its people had to go through the growing pains of trying and failing to expand and build state-level societies.

Başur Höyük cemetery, which was only discovered in 2014, was in use during a time when one of those expansion attempts collapsed, according to Hassett. Little is known of this period, which is followed by the establishment of the world’s first state-level societies, in Mesopotamia.

“We are tantalizingly close to getting more detail on the actual human actions and new behaviors, new rituals, new ways of being that lead us to early states or civilizations,” says Hassett.

A show of power

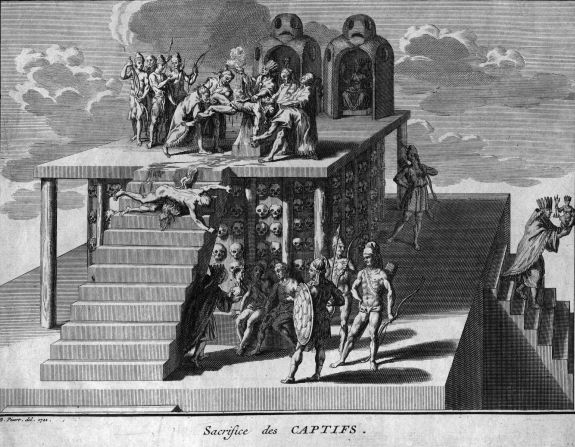

Evidence of human sacrifice has been found in various parts of the world, but motivations for the practice have varied. The Aztecs, for instance, sacrificed humans as offerings to the gods.

For ancient Mesopotamians, transitioning into early states meant large groups of people were figuring out how to live closely together, organize themselves, and establish social rules – all while dealing with social stresses caused by the changes and vying for authority.

Read: The Voynich manuscript: Will this medieval mystery ever be solved?

Amid these adjustments, Hassett says human sacrifices – along with rich grave goods – likely would have been intended to demonstrate power within a group of people. She says this also would’ve included an elaborate burial ceremony, where those in attendance were witnesses to the power display.

“The power over human life is kind of the ultimate social power,” says Hassett. “If you are able to dispose of humans as you would gifts, or other treasure, if those things are in your possession, then by displaying this you’re actually demonstrating power.”

Augusta McMahon, a Mesopotamian archaeologist from the University of Cambridge, echoes this belief.

McMahon says the skeletons at Başur Höyük predate other examples of adult human sacrifice in Mesopotamia, such as at those at The Royal Cemetery at Ur, in modern-day southern Iraq.

The Royal Cemetery of Ur, located in modern-day southern Iraq and which came about 500 years after the Başur Höyük cemetery, shows examples of mass adult retainer sacrifices.

McMahon clarifies the tombs with human sacrifices in them are only a small number of the total graves at Ur, and that while shocking, human sacrifices in Mesopotamia were quite rare.

Hassett is hopeful the Başur Höyük cemetery will yield more answers over time. She is set to start analyzing ancient DNA to find any family relationships or connections to others in the surrounding graves at the cemetery, as well as more clues as to the social status of the children and young adults found in the tomb.

Read: Scotland’s 5,000-year-old carved stone balls shrouded in mystery