Editor’s Note: CNN’s Julie Guinan went to Guatemala, as part of a CARE Learning Tour.

Story highlights

Gender-based violence is at epidemic levels in Guatemala

According to the United Nations, two women are killed in Guatemala every day

Five abuse survivors known as La Poderosas have been appearing in a play based on their real life stories

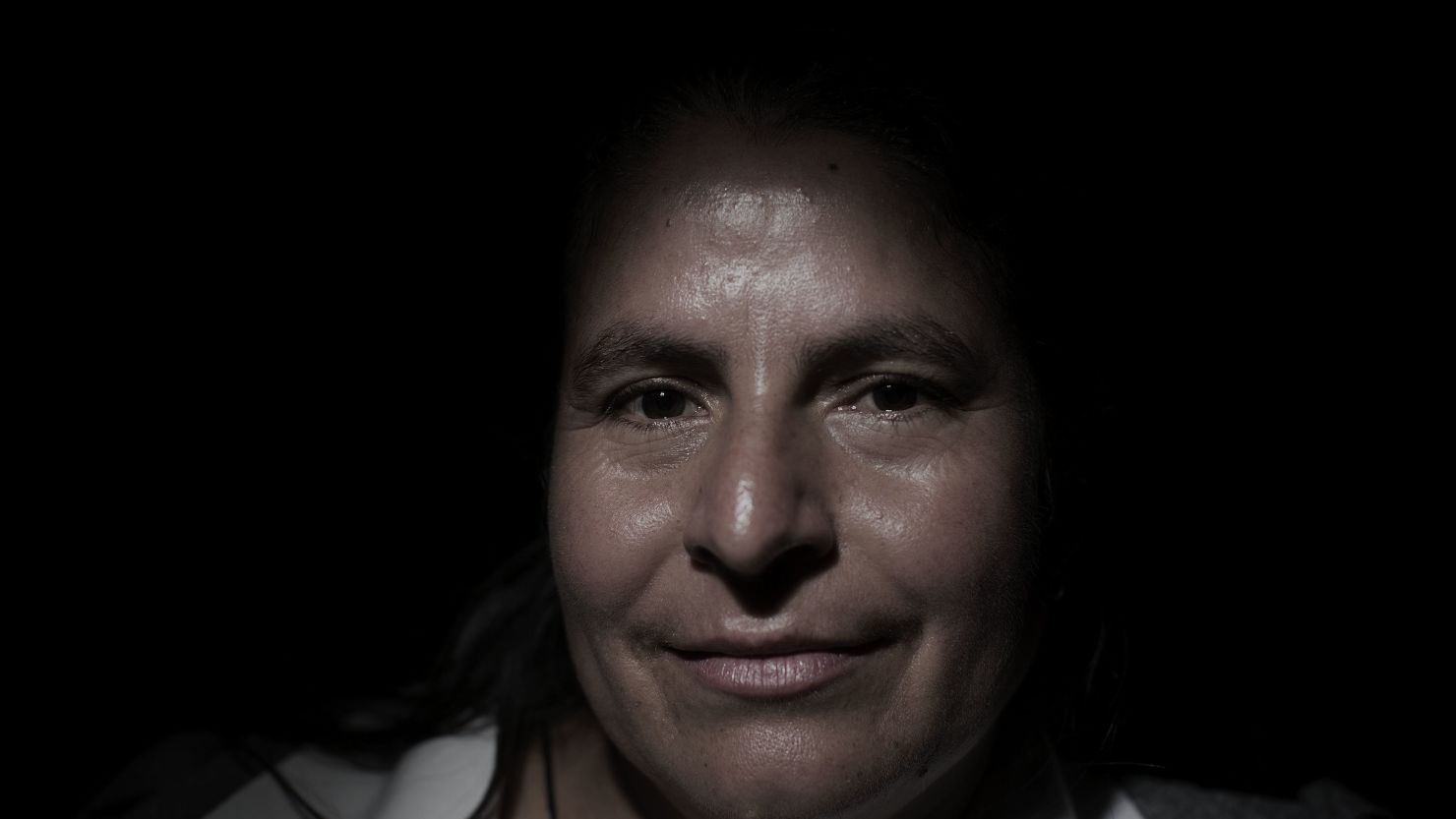

For 12 years Adelma Cifuentes felt worthless, frightened and alone, never knowing when her abusive husband would strike.

But as a young mother in rural Guatemala with three children and barely a third grade education, she thought there was no way out.

What began as psychological torment, name-calling and humiliation turned into beatings so severe Cifuentes feared for her life. One day, two men sent by her husband showed up at her house armed with a shotgun and orders to kill her. They probably would have succeeded, but after the first bullet was fired, Cifuentes’ two sons dragged her inside. Still, in her deeply conservative community, it took neighbors two hours to call for help and Cifuentes lost her arm.

But the abuse didn’t stop there. When she returned home, Cifuentes’ husband continued his attacks and threatened to rape their little girl unless she left. That’s when the nightmare finally ended and her search for justice began.

Guatamala’s past still haunts

Cifuentes’ case is dramatic, but in Guatemala, where nearly 10 out of every 100,000 women are killed, it’s hardly unusual.

A 2012 Small Arms Survey says gender-based violence is at epidemic levels in Guatemala and the country ranks third in the killings of women worldwide. According to the United Nations, two women are killed there every day.

There are many reasons why, beginning with the legacy of violence left in place after the country’s 36-year-old civil war. During the conflict, atrocities were committed against women, who were used as a weapon of war. In 1996, a ceasefire agreement was reached between insurgents and the government. But what followed and what remains is a climate of terror, due to a deeply entrenched culture of impunity and discrimination. Military and paramilitary groups that committed barbaric acts during the war were integrated back into society without any repercussions. Many remain in power, and they have not changed the way they view women.

Some 200,000 people were either killed or disappeared during the decades-long conflict, most of them from indigenous Mayan populations. Nearly 20 years later, according to the Security Sector Reform Resource Centre, levels of violent crime are higher in Guatemala than they were during the war. But despite the high homicide rate, the United Nations estimates 98% of cases never make it to court. Women are particularly vulnerable because of a deep-rooted gender bias and culture of misogyny. In many cases, femicide – the killing of a woman simply because of her gender – is carried out with shocking brutality with some of the same strategies used during the war, including rape, torture and mutilation.

Explosion in violence

Mexican drug cartels, organized criminal groups and local gangs are contributing to the vicious cycle of violence and lawlessness. Authorities investigating drug-related killings are stretched thin, leaving fewer resources to investigate femicides. In many cases, crime is not reported because of fear of retaliation. Many consider the Guatamalen National Civil Police, or PNC, corrupt, under-resourced and ineffective. Even if a case does get prosecuted, according to Human Rights Watch, the country’s weak judicial system has proved incapable of handling the explosion in violence.

Prevailing culture of machismo

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges facing women in Guatemala is the country’s deeply rooted patriarchal society.

According to María Machicado Terán, the representative of U.N. women in Guatemala, “80% of men believe that women need permission to leave the house, and 70% of women surveyed agreed.” This prevailing culture of machismo and an institutionalized acceptance of brutality against women leads to high rates of violence. Rights groups say machismo not only condones violence, it places the blame on the victim.

Make an impact: Help stop gender-based violence

The political will to address violence against women is slow to materialize.

“Politicians don’t think women are important,” says former Secretary General of the Presidential Secretariat for Women Elizabeth Quiroa. “Political parties use women for elections. They give them a bag of food and people sell their dignity for this because they are poor.”

Lack of education is a major contributor to this poverty. Many girls, especially in indigenous communities don’t go to school because the distance from their house to the classroom is too far.

Quiroa says “They are subject to rape, violence and forced participation in the drug trade.”

Signs of progress

Although the situation for girls and women in Guatemala is alarming, there are signs the culture of discrimination may be slowly changing. With the help of an organization known as CICAM, or Centro de Investigación, Cifuentes was finally able to escape her husband and get the justice she deserved. He is now spending 27 years behind bars.

Cifuentes is using her painful past to provide hope and healing to others through art.

Since 2008, she and four other abuse survivors known as La Poderosas, or “The Powerful,” have been appearing in a play based on their real life stories.

The show not only empowers other women and discusses the problem of violence openly, but it also offers suggestions for change. And it’s having an impact. Women have started breaking their silence and asking where they can get support. Men are reacting, too. One of the main characters, Lesbia Téllez, says during one presentation, a man stood up and started crying when he realized how he had treated his wife and how his mother had been treated. He said he wanted to be different.

The taboo topic of gender-based violence is also being acknowledged and recognized in a popular program targeting one of Guatemala’s most vulnerable groups, indigenous Mayan girls. In 2004, with help from the United Nations and other organizations, the Population Council launched a community-based club known as Abriendo Oportunidades, or “Opening Opportunities”. The goal is to provide girls with a safe place to learn about their rights and reach their full potential.

Senior Program Coordinator Alejandra Colom says the issue of violence is discussed and girls are taught how to protect themselves. “They then share this information with their mothers and for the first time, they realize they are entitled to certain rights.”

Colom adds that mothers then become invested in sending their daughters to the clubs and this keeps them more visible and less prone to violence.

The Guatemalan government is also moving in the right direction to address the problem of violence against women. In 2008, the Congress passed a law against femicide. Two years later the attorney general’s office created a specialized court to try femicides and other violent crimes against women. In 2012, the government established a joint task force for crimes against women, making it easier for women to access justice by making sure victims receive the assistance they need. The government has also established a special 24-hour court to attend to femicide cases. On the global front, the International Violence Against Women Act was introduced in the U.S. Congress in 2007; it has been pending ever since. But last week the act was reintroduced in both the House and Senate. If approved, it would make reducing levels of gender-based violence a U.S. foreign policy priority.

Pehaps the most immediate and effective help is coming from International nongovernmental organizations, which are on the front lines of the fight against gender-based discrimination in Guatemala.

Ben Weingrod, a senior policy advocate at the global poverty fighting group CARE, says, “We work to identify and challenge harmful social norms that perpetuate violence. Our work includes engaging men and boys as champions of change and role models, and facilitating debates to change harmful norms and create space for more equitable relationships between men and women.”

But the job is far from over. While there is tempered optimism and hope for change, the problem of gender-based violence in Guatemala is one that needs international attention and immediate action.

Cifuentes is finding strength through the theater and the support of other abuse survivors, which has allowed her to move forward. But millions of other women trapped in a cycle of violence are facing dangerous and frightening futures. For them, it’s a race against time and help cannot come soon enough.