Story highlights

NEW: Costa Concordia captain Francesco Schettino convicted, gets 16 years for shipwreck

Schettino comes from seafaring background and went to well-regarded nautical institute

Schettino has blamed colleagues, and even the ship itself for the disaster

Thrust from obscurity to notoriety overnight, Captain Francesco Schettino is the man at the center of recriminations over the Costa Concordia cruise ship disaster.

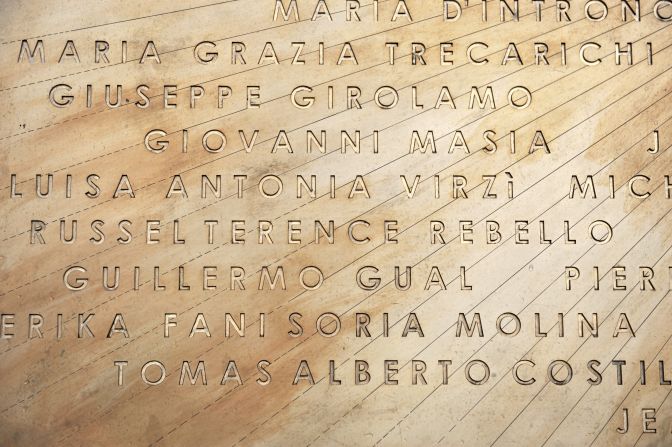

The liner capsized after it struck rocks off Italy’s Giglio Island in the Tyrrhenian Sea in January 2012. No one died on impact but 32 lives were lost during the subsequent chaotic evacuation of the 4,200 people on board the ship.

On Wednesday, an Italian court found Schettino guilty of manslaughter and other charges related to the wreck, and sentenced him to 16 years in prison.

Over the past two years, the judges in the captain’s trial have heard from a wide variety of people, including passengers, crew members and technical experts.

Just before the judges got the case, the captain took the opportunity to speak again.

Breaking down in tears, Schettino recalled that January day three years ago.

“I died along with the 32 others,” he said. And since then, Schettino insisted, he’s become a victim, processed by a “media meat grinder.”

‘A mystery so far’

Schettino, 52 at the time of the accident, admitted he had been “showboating” when he sailed the luxury cruise liner so close to the island of Giglio, where submerged rocks tore through the hull. However, he said earlier the rocks were uncharted, and he did everything he could to preserve the lives of crew and passengers.

The captain has previously pointed the finger at the Indonesian helmsman, whom he said did not speak English or Italian well enough to understand his orders, as well as the Costa cruise company for not providing maps with the rocks he hit appropriately marked.

READ MORE: How Costa Concordia was raised

Schettino has also blamed the ship itself, saying the generators did not work so the elevators did not function, hindering some people’s escape.

Schettino’s lead lawyer Domenico Pepe began closing arguments on Monday by saying the champagne bottle used to christen the ship when it was put into service in 2006 did not break.

“Everything about this ship and this process since then has been a mystery so far,” he said.

Earlier in the trial Moldovan dancer Dominca Cemortan, who dined with the captain and was with him on the command bridge, gave evidence for the prosecution.

Cemortan boarded the ship as a passenger but had worked on another Costa Cruises ship captained by Schettino a few weeks earlier. The dancer admitted on the stand under duress that she and Schettino had a sexual relationship, something the captain had previously denied. She also accused Schettino of calling for a helicopter to rescue him, which he has denounced her for in a separate lawsuit.

‘Constantly trained’

A native of Castellamare di Stabbia, near the southern city of Naples, Schettino comes from a seafaring family, Italy’s Corriere della Sera newspaper reports.

He graduated from the well-regarded Nino Bixio nautical institute in Piano di Sorrento, in Naples province, 30 years ago, according to the news agency Adnkronos.

He joined Costa in 2002 as a safety officer, served as a staff captain, and was appointed captain in 2006, according to the cruise line. Like all Costa masters, Schettino was “constantly trained, passing all tests.”

Costa chairman Pier Luigi Foschi, who retired after the disaster, had said Schettino had never been involved in an accident before. However, in court it was revealed that in June 2010 he scraped his ship, the Aida Blu, against a port wall in Germany.

After the 2012 accident Foschi played down the possibility that alcohol played a role in the disaster, saying he did not believe Schettino drank, and that all crew were subject to random drug and alcohol tests by Costa Cruises.

But Foschi placed the blame for the wreck squarely on the captain, saying it was his choice to deviate from frequently traveled routes in order to “impress the passengers,” as Schettino admitted.

Schettino is also accused of abandoning his passengers, who were unable to look after themselves, and to whom he had a responsibility as captain, when he left the ship before they did.

Pepe tried to explain why his client left the ship ahead of so many passengers.

He used a graphic to illustrate the inclination of the ship at the time Schettino apparently lost his balance and fell into the lifeboat that took him to shore. He said that once on shore, Schettino was able to conduct the rescue operation and that he never lost control of the operation.

The attorney also addressed the famous exchange between Gregorio De Falco – commander of the Livorno Port Authority the night of the accident – and Schettino, during which De Falco told Schettino to “get back on board for f**k’s sake.” Pepe called De Falco’s tone degrading and said the commander was unprofessional and egotistic at a moment when he should have been a voice of calm.

Schettino initially appears to play down the scale of the disaster, saying only that a “technical failure” has occurred. He then tells an official he has abandoned the vessel, according to the transcripts, which prosecutors say match those used in their investigation.

But as the official questions his decision, Schettino appears to reverse course and says he did not abandon ship but was “catapulted into the water” after the ship ran into a rock, began taking on water and started listing.

As the night unfolds, the coast guard commander repeatedly questions why Schettino, as captain, is not on the ship when passengers are still aboard.

But Schettino appears unwilling either to go back on board or to take charge of the desperate evacuation efforts, the transcripts reveal.

In addition to questions over how Schettino handled himself after the wreck, questions also lingered about whether the captain should have ordered an evacuation sooner and why no “mayday” distress signal was sent.

READ MORE: What the Concordia leaves behind

CNN’s Peter Wilkinson and Barbie Latza Nadeau contributed to this report.