Editor’s Note: Is ISIS actually sealing its own fate with the release of these gruesome beheading videos? How effective will military strikes really be? CNN hosts an email discussion on the threat posed by ISIS and how the U.S. should respond. CNN terrorism analyst Paul Cruickshank, former CIA analysts and terrorism experts Cindy Storer and Nada Bakos, and Brookings Institution fellow Shadi Hamid offer their takes. Their comments have been edited for clarity and style.

Story highlights

CNN hosts an email conversation on ISIS with four terrorism experts and analysts

Paul Cruickshank: ISIS miscalculated effect of beheading videos on U.S. public

Nada Bakos: ISIS brutality may backfire; Shadi Hamid: U.S. allying with autocrats a problem

Cindy Storer: Is ISIS' Australia beheading plot something we can now expect worldwide?

The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria has managed to shock the world by releasing videos of the executions of two American journalists, a British aid worker and now a French tourist. The U.S. said Thursday that it believes it has identified the man in the video showing the execution of James Foley.

Either way, do you think the brutality on display could prove counterproductive? Is ISIS actually sealing its own fate in the long term with this tactic?

Paul Cruickshank: Yes, I think these videos will ultimately prove counterproductive to ISIS. The group’s main goal is to create an Islamic state in Syria, Iraq and the surrounding countries. But these videos, along with the videos they post of themselves carrying out indescribably brutal massacres of thousands of Syrians and Iraqis, have shocked the world and rallied a growing coalition of powers to confront them. And even more importantly, ISIS’s extreme brutality will inevitably eventually lead to a backlash from Sunnis across Iraq and Syria.

But while these videos horrify the vast majority of Muslims, they resonate with the group’s radical support base around the world. This means that in the short term, they’re generating a recruitment windfall. The beheadings make ISIS look 10 feet tall in the eyes of these extremists, able to stand up to a superpower waging a war on Islam and strike terror in the hearts of the disbelievers. Their selective and distorted interpretation of the Quran makes them convinced these brutal executions are sanctioned by God.

Some analysts say the beheadings were designed to goad the United States into military intervention in Iraq and Syria. I don’t agree. Everything we know about the group suggests their main goal has been creating an Islamic state, so why would they want to deliberately jeopardize this?

So I think the beheadings were an attempt by the group at a calibrated response: They showed their supporters around the world they were responding to U.S. strikes in Iraq and satisfied their bloodlust, but they stopped short of the kind of attack that in their mind would invite an overwhelming American response. But they seem to have miscalculated badly, because they didn’t understand how the American people would respond.

Paul Cruickshank is an analyst on terrorism for CNN and an alumni fellow at the Center on Law and Security at New York University’s School of Law

Shadi Hamid: I think whether this backfires for ISIS depends, in large part, on what we end up doing. ISIS is a protostate that controls large swaths of territory and, as Paul points out, is much more interested in governance than al Qaeda ever was. The problem now is that we are allying with some of the most repressive regimes in the region – Saudi Arabia and Egypt, for instance – to fight ISIS. These regimes are more than happy to use the guise of counterterrorism to wage war on their political opponents at home. If lack of democracy and failure of governance contribute to the appeal of extremism, then excessive reliance on allies with such problems – and a problematic regional order – doesn’t exactly inspire confidence.

Of course, we live in the real world, and that means working with autocratic allies who don’t share our values or interests. But without a broader vision that takes into account the deeper roots of regional dysfunction, ISIS and groups similar to it may be able to thrive.

That broader vision is certainly lacking in Syria, which remains the gaping hole in our ISIS strategy. Our plan to train 5,000 fighters over one year is simply not enough to make a significant difference. In practice, this means that for all our rhetoric about “destroying” ISIS, our policy, at least for now, is effectively one of containment.

Meanwhile, there remains a temptation to coordinate with [Syrian President Bashar] al-Assad against ISIS, which would allow ISIS to usurp the mantle of Sunni resistance against a hated regime. The administration has ruled out any such coordination, but airstrikes against ISIS without a serious plan to boost mainstream rebel forces may still end up benefiting al-Assad (whose brutal policies are at the root of ISIS’s rise to prominence in the first place).

In short, ISIS has angered the American people and the American government with its unabashed brutality, but so far our response has been remarkably lackluster, especially considering that ISIS has been a threat for well over a year. It is impossible to know what ISIS’s intentions were when it beheaded James Foley and Steven Sotloff. Some of it may have been beyond rational motivation, the product of a rather potent mix of bloodlust, hubris, and messianism. We cannot know for sure, but we do know that militant and extremist organizations, even those with “states,” can benefit from the overreach and misguided adventurism of greater powers. In this particular case, the Obama administration seems doomed to both overreach and underreach. Whatever the appropriate characterization of President Obama’s approach, I fear that ISIS – and perhaps, one day, its successors – will get away with murder, and worse.

Shadi Hamid, a fellow at the Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World at the Brookings Institution’s Center for Middle East Policy, is the author of “Temptations of Power: Islamists and Illiberal Democracy in a New Middle East.”

Nada Bakos: Is this going to backfire on ISIS? Yes and no. If the old adage that there is no such thing as bad press holds true, ISIS is definitely garnering attention with these tactics. Recruits are also attracted to the perceived flurry of success by ISIS capturing territory and providing a governance structure so quickly. Historically, however, there is precedent of rejection by members of a terrorist organization and the local populace over brutal tactics – think of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s al Qaeda in Iraq and the now defunct Armed Islamic Group in Algeria, known as the GIA.

ISIS is an evolution of al Qaeda in Iraq, which enacted a brutal terrorist strategy against the advice of al Qaeda’s central leadership. Eventually, the local population in Falluja tired of being subjugated to his brutality and rejected his organization. Jabhat al-Nusra applied this lesson in Syria through charitable efforts and governance to galvanize local support and generate influence among Syrians.

Similarly, in the 1990s when the GIA violently opposed a secular government in Algiers, part of the leadership broke away and started another organization after realizing the brutality was alienating the Algerian populace.

So I don’t think ISIS will self-implode because of these videos – they’ve managed to embed themselves with a governance structure so quickly that they will be hard to root out. ISIS is also full of former Baathists who may or may not be on board with ISIS’ ideology but are likely behind some of the major military successes.

That said, if an inclusive government is formed in Iraq, it’s possible they’ll turn their back on ISIS. And the intensity of their campaign may well be diminished after the local populations become weary of their brutality to the point of coalescing militant groups to fight against them.

Nada Bakos is a former CIA analyst and was a member of the team created to analyze the relationship between Iraq, al Qaeda and the September 11 attacks.

Cindy Storer: I’m largely in agreement, but come at this from a different angle. The beheadings conducted by the self-proclaimed “Islamic State” both attract and repel. The question is which of these force will be stronger.

On the one hand, as Nada and Paul said, they help recruit other jihadis to [Abu Bakr al-]Baghdadi’s cause. They are a symbol that Baghdadi won’t compromise with the “enemy” as many jihadis believe current al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri has. Al-Zawahiri has opposed beheadings for years because they generate bad press, even though beheading has been a common practice in Islamic conquests since the earliest days.

This wouldn’t necessarily be a problem for us except that Baghdadi has upped the ante by declaring a universal Caliphate in direct competition with al Qaeda. So he isn’t just interested in Iraq and Syria – he wants it all. And he’s further legitimizing his claim in the eyes of the disgruntled by establishing a working government that follows early Islamic laws of conquest in the territory he takes.

All this is causing tremors in the entire jihadi movement, worldwide. It reminds me of the late 1990s, when the Egyptian Islamic Group declared a ceasefire with the Egyptian government. Following this, many of their followers and associated groups switched their allegiance to al Qaeda.

On the other hand, al-Zawahiri isn’t wrong about the reaction of the rest of the world, especially the U.S. Al Qaeda learned that lesson the hard way. To the extent that the people of the region – and those of other parts of the world where jihadis have a significant presence, such as parts of Africa – are seen to reject Baghdadi’s tactics, Baghdadi’s vision loses.

And there’s the rub. A too heavy outside hand or a coalition of dictators risks further radicalizing many who yearn for the Caliphate, and who would then blame these forces for their setback, rather than blame ISIS. And if good government and security doesn’t follow victory, the whole cycle continues regardless.

Cindy Storer is a 21-year veteran analyst of the CIA who specializes in terrorism and intelligence education. She is a lecturer in intelligence and national security at Coastal Carolina University in South Carolina.

Hamid: Cindy, you’re right when you suggest that ISIS is a “revolutionary” organization in a way that al Qaeda never quite was (in a rather backwards-looking away, of course). I thought Graeme Wood put it particularly well in in one of the only pieces I’ve read that takes ISIS’s religious inspirations seriously: “ISIS’s meticulous use of language, and its almost pedantic adherence to its own interpretation of Islamic law, have made it a strange enemy, fierce and unyielding but also scholarly and predictable.”

This is where ISIS’s aspirations to governance become critical, and where Obama’s description of the group as a “terrorist organization, pure and simple” seems both problematic and detached. Emphasizing the distinctive nature of ISIS – and getting it across – becomes difficult in a public discourse that is very focused on us, dealing with our Iraq demons and so on.

So, for example, the religious pedigree of ISIS, and the kind of intra-Jihadist competition that Cynthia pointed to, are important – and certainly interesting – to those of us who study Islamist movements. But how much of the historical and religious nuance is, as they say, “policy relevant?” To what extent should this impact the actual decisions senior U.S. officials are making and will make? I’m less sure about this part of it, and I’d be curious what others think.

Storer: Shadi, that’s a really good question that I’ve been struggling with myself. I’m just going to throw some ideas out that have been knocking about in my head.

The plot in Australia to behead some random person might – might – be one sign that we should be concerned. Is that the type of plot we can now expect worldwide?

Another concern is that we know from history that when groups compete that sometimes they try to one up each other. With that in mind, can we imagine what a terrorist bidding war might look like between al Qaeda and ISIS?

Conversely, although the al Qaeda affiliates have sworn bayat (allegiance) to al-Zawahiri, there appears to have been some internal debate. Might some swing over to ISIS eventually if they continue to show gains?

Nada – you pointed out that although the brutality eventually backfires, ISIS will be hard to root out. What are we willing to risk in the meantime?

Cruickshank: Shadi, you are being diplomatic when you say that Syria is the gaping hole in America’s ISIS strategy. At a time when “moderate” rebels are on life support in Aleppo, Pentagon press spokesman Navy Rear Adm. John Kirby has said it will take at least 12 months to vet and train 5,000 of them in Saudi Arabia. Increasingly squeezed by al-Assad and ISIS, will moderate rebels still exist as any sort of force in a year’s time?

Moreover, it’s far from clear “moderate” rebel groups like the Free Syria Army (FSA) will actually take the fight to ISIS. Their priority is fighting the al-Assad regime.

Another roadblock is the fact that the FSA has been cooperating on the ground with Jabhat al-Nusra, al Qaeda’s affiliate in Syria. Can the United States safely provide weapons and money to a group working with a group committed to launching terrorist attacks on the United States? According to the U.S. government, al-Nusra has connections to al Qaeda veterans who have migrated to Syria from the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region.

U.S. officials say these operatives, known as the Khorasan group, are actively plotting attacks against Western targets. They also say they fear al Qaeda in Yemen is sharing bomb-making technology to bring down commercial passenger jets with Jabhat al-Nusra.

U.S. military officials are privately aware of these complex challenges. That’s why last week, Gen. Martin Dempsey, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, set out the limited goal of “disrupting” ISIS in Syria. But the worry is that creates a window of vulnerability. The airstrikes in Iraq have stirred the hornets nest, and ISIS may now seek to retaliate with attacks on the homeland of Western countries.

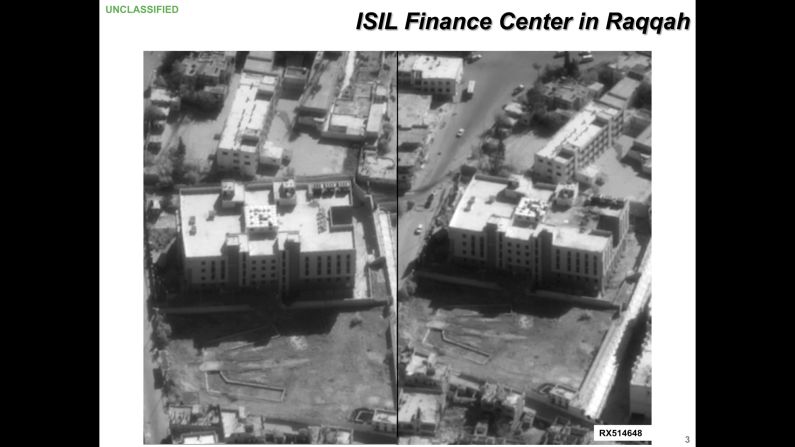

Their capability shouldn’t be underestimated. They have training camps on a scale last seen in Taliban-run Afghanistan, a thousand Western recruits and tens of millions of dollars in cash reserves. So the group will retain the capability in the months ahead to train Western extremists to return back home to launch attacks.

Hamid: You know, it’s really striking just how detached our Syria policy is from what’s actually happening in Syria. So much of the debate in Washington is really about us, even though ISIS is a greater threat to the “Middle East” – whatever that now is – than to the homeland. To state the obvious, it’s not always about us.

Mosul fell in June, so there’s really no excuse for what came next in Syria. As a New York Times op-ed points out, “though Western attention is drawn to Iraq, it is Syria that has witnessed the most significant ISIS gains” in recent months. ISIS was closing in on Deir Ezzour in eastern Syria. For weeks, FSA rebels begged for assistance but were ignored, despite pleading their case to Samantha Power [U.S. ambassador to the United Nations].

And so it goes again in Aleppo, where mainstream rebel forces find themselves sandwiched between ISIS and the al-Assad regime. As Paul says, the rebels are “on life support” in Aleppo. We can have all the debates we want about whether we will have a strategy at some later point. We can debate whether training 5,000 rebels over a year will be enough. But while we wait for our Syria strategy, the very people we’re supposedly hoping to support are at risk of yet another defeat in Aleppo, and this one will be difficult to recover from.

Cruickshank: I think we saw a really significant development late Sunday when ISIS spokesman Abu Muhammad al Adnani, a heavyweight figure in the group, called for lone wolf attacks by ISIS supporters in the United States and Europe. That was the first time I’m aware of that a senior ISIS leader explicitly called for attacks on the home soil of Western countries. While al Qaeda and al Qaeda in Yemen have called for such attacks before, ISIS’s call will carry more weight because its radical supporters around the world believe the “Islamic State” has sovereign authority over Muslims worldwide.

Al-Adnani said ISIS “did not initiate the war … it is you who started the transgression against us, and thus you deserve blame and you will pay a great price.” Propaganda that may be, but I think al-Adnani’s words provide further evidence ISIS was not actually trying to goad the United States into a war against it. Rather, the group miscalculated what the Western response would be to killing American and British hostages.

But now the gloves have come off. In this new tape, al-Adnani is basically saying “bring it on” to the United States and other Western powers. Not only did he promise to defeat any Western forces sent to Iraq and Syria, but he also promised ISIS itself will carry out “raids” on Western soil afterward.

There will be significant concern now that ISIS supporters in the West may try to carry out attacks in the days and weeks ahead in ISIS’s name. There will also be concern that hundreds of Syria Jihad veterans back in Europe may also answer the call.

So what do you make of the U.S. military effort launched this week?

Storer: They might buy some much needed breathing room, but they’re not a solution in and of themselves. As we’ve all said, what happens after in the affected areas is critical. The group has significant allies/adherents elsewhere, and could move some operations if those allies aren’t confronted simultaneously.

And I’d also add as a final thought that this whole “mess” is an example of what we can expect in Afghanistan once U.S. troops withdraw.

Hamid: I think the strikes are a first step, but what’s the end game here? Without being embedded in a broader, long-term strategy, I worry that they might actually prove counterproductive, whether by strengthening the al-Assad regime’s position, undermining rebel morale or helping ISIS to maintain local support.

This is where objectives matter, and as I said earlier, I’m afraid that our goals in Syria and the goals of the very local forces that are supposedly critical are misaligned in rather striking ways. The Obama administration is adopting what is primarily a counterterror strategy against a group that is not primarily a terrorist organization.

This might be all well and good if the goal is to simply degrade ISIS’s capabilities. But even there, we run into problems. These strikes against ISIS are likely, at least in the short to medium-run, to increase the likelihood of attacks against the U.S. and U.S. interests. As Paul noted, ISIS spokesman al-Adnani’s statement included the first ever explicit call by a senior ISIS leader for attacks against Western civilians.

We need to have an honest discussion about why we’re doing what we’re doing. We alternate between narrowly defining our interests while suggesting to our allies – in this case the Syrian rebels – broader, more ambitious objectives, only to quickly disappoint them when they find out we aren’t quite serious.

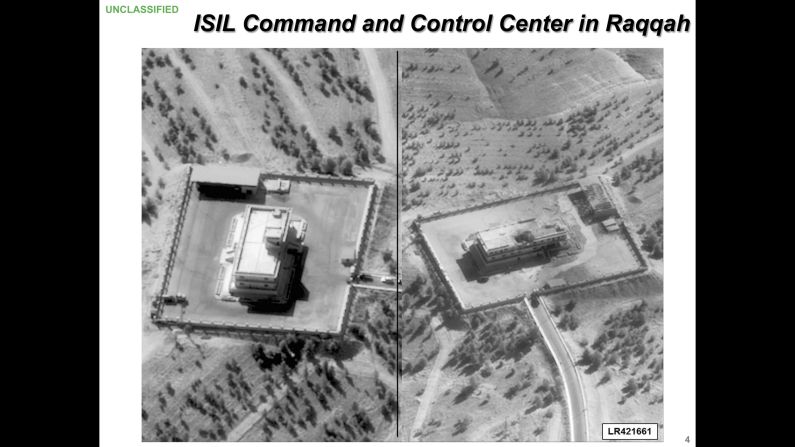

Cruickshank: Yes, U.S. and coalition airstrikes in Syria may succeed in taking out some of ISIS training camps and command and control facilities, and they will undoubtedly constrain their freedom of movement. But they won’t drive the group out of areas they control. We are getting reports ISIS fighters have been taking up lodgings among civilians in Raqqa, effectively using them as human shields. It will be virtually impossible to target them without also killing many civilians.

This is probably why after the initial bombardment Monday night, we are already seeing a slowing in the pace of U.S. strikes against ISIS. American spy satellites and drones can spot large-scale ISIS formations and training camps, but they can’t tell who is who inside buildings in urban areas. U.S. intelligence doesn’t seem to have good intelligence on the location of ISIS’s leadership. If they had, they would have been targeted in the first strikes, like they did for the Khorasan group.

The worry now is that ISIS will initiate a crash program to launch terrorist attacks in the West. They don’t even need training camps to do this. They can train Western recruits almost everything they need to know inside apartment buildings in Raqqa.

Bakos: I would say this. The airstrikes inside of Iraq could have a long-term impact because we are working with forces on the ground who can act on the strikes quickly and gain momentum. In Syria, it’s a different story – without anyone to follow up on the ground, ISIS has likely scattered into the nearby neighborhoods and will remain low profile for some time. It may slow down their ability to also capture more territory.

What the airstrikes won’t do is offer a long-term solution to degrading ISIS and the al Qaeda cell referred to as Khorasan. Until there’s a clear strategy to plug the power vacuum inside of Syria, a long-term solution isn’t on the horizon.

A final question: What is the single thing that you would like to see done to counter ISIS?

Cruickshank: The one thing that will make the biggest single difference is splitting off Sunni tribes from ISIS in Iraq. But that will require a genuinely inclusive approach from Iraqi government. Despite some progress, don’t hold your breath on that front. The delivery of suitcases with millions of dollars of cash may be more persuasive in the short term, like during the Anbar awakening.

Bakos: Along with our allies in the region, build a solid governance plan to put in place if ISIS starts to crumble with our allies in the region. The political calculus is just as, if not more, important than the military action.

Hamid: I know the very thought of it is unpopular in today’s climate, but this is ultimately more about “nation-building” and “state-building” than it is about counterterrorism. In addition to coming up with an actual Syria strategy, we need to develop a longer-term vision that takes questions of democracy, reform and governance seriously. Obama needs his own “freedom agenda” to go along with this new “war on terror.” That will require a willingness to put pressure on the very Arab allies we’re working with to fight ISIS.

Storer: Recent days remind us too that we are still at war with al Qaeda, and they are still trying to kill us at home. But watch – in a few weeks there will be calls to declare victory and go home, so to speak. What we need in addition to everything everyone has said is staying power. How many times will we let al Qaeda reinvent themselves?

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine.