Editor’s Note: John D. Inazu is an associate professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis. He teaches courses in criminal law, religion and the First Amendment. He is the author of “Liberty’s Refuge: The Forgotten Freedom of Assembly.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the writer.

Story highlights

John Inazu: Slogans like "We are all Columbine" aren't true, nor is "We are Ferguson"

Inazu: Not all of us live in those circumstances, but we all made Ferguson come into being

He says we reinforce racial and class divisions that affect neighborhoods, schools

Inazu: We allow a system that disproportionately harms black men and neglects inequality

We all know the slogans meant to express empathy and solidarity: “We are Columbine.” “We are all New Yorkers.” “I am Trayvon Martin.” The “We are Ferguson” messages have already begun, and we will likely see more.

The well-intended connections seldom work. Most of us are not Columbine because most of us did not lose children in our community in a high school mass shooting. We are not all New Yorkers because only some of us experienced the aftermath of 9/11 at Ground Zero. I am not Trayvon Martin because I am not a black male.

Are we Ferguson? That’s a harder question.

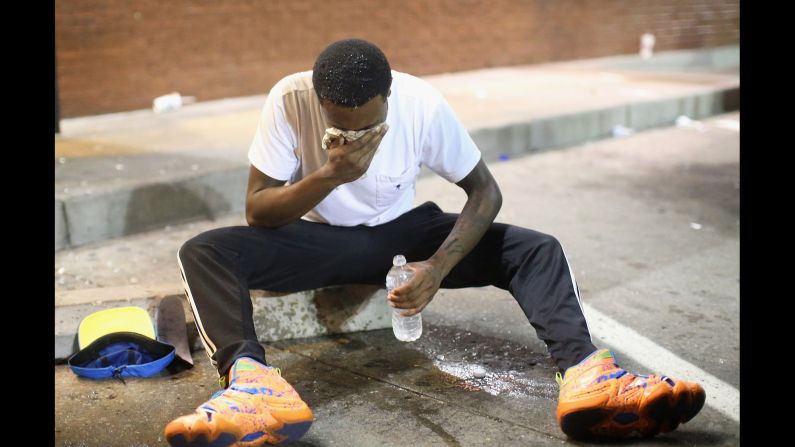

Ferguson has a median household income of $36,645 and an unemployment rate topping 13%. And as the world now knows, Ferguson’s overwhelmingly white police force arrests blacks at a pace nearly four times higher than whites. On the other hand, although you wouldn’t know it from most of the news coverage, Ferguson is also one of the most racially integrated municipalities in Missouri. It includes not only working-class blacks and white professionals, but also black professionals and working-class whites. And many of Ferguson’s residents bridge racial and socioeconomic lines in their neighborhoods.

With all of its complexities, Ferguson does not sound like my world.

I teach at Washington University, where most of my colleagues and students are white. I shop at mostly white places that feel safe and convenient. Most of the contentious issues in my mostly white neighborhood are about bike paths and trees. Many of you live in my world.

It would be easy for those in my world to say we are not Ferguson. But highlighting our differences misses something important: We are part of the reason for the circumstances that it confronts today. We may not be Ferguson, but we helped make Ferguson.

That we made Ferguson is reflected in politics and geography. Ferguson is one of dozens of municipalities nestled around St. Louis. Like many large urban areas in this country, each St. Louis municipality is separately incorporated with its own police force, schools and tax base.

I pass through three of them to get to my local grocery store – and Ferguson’s burned down QuikTrip is just seven miles from my workplace and house. In the best cases, these divisions create the possibility for good local government and communities where friendship and civic involvement can flourish.

In the worst cases, they provide opportunities for self-interest and exploitation. St. Louis has some of the best; it also has some of the worst. The worst cases are often tied to the issues of race and class.

We made Ferguson because our choices reinforce racial and class divisions that manifest not only in cultures and attitudes, but also in schools, neighborhoods, churches and businesses.

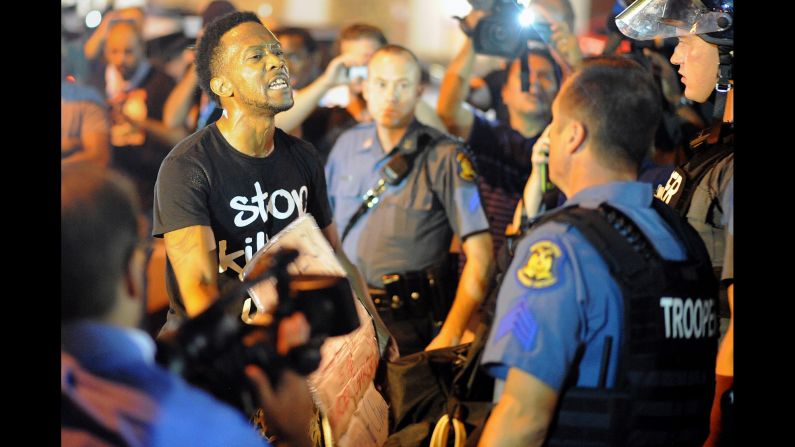

Many of us do not live in large urban areas. But we, too, made Ferguson because we’re complicit in a system of criminal justice that disproportionately harms black men, and therefore, the black community. We made Ferguson because we do not address the vast and growing injustices for America’s poor – black and white.

We made Ferguson because too many of us would rather tweet than get involved in the messiness of local politics and community building. The hard work of solving problems doesn’t happen from hashtag campaigns or writing blog posts and articles – like this one.

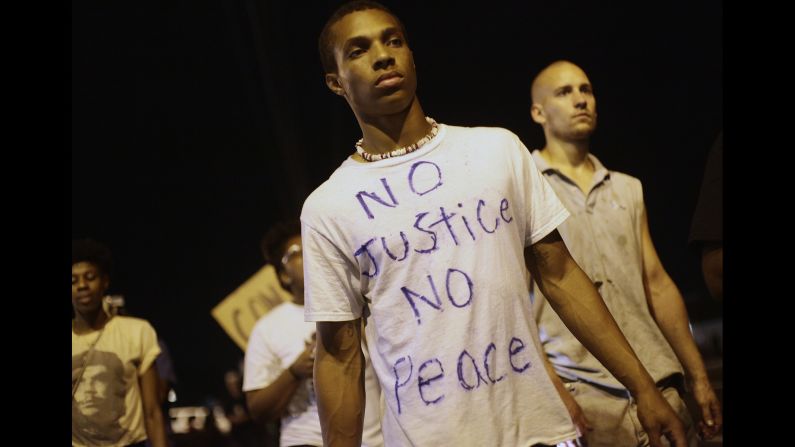

We made Ferguson because we have more tolerance for riots after sporting events than for citizens protesting injustice. We stand by and watch the government’s most egregious violations of our First Amendment rights when the protests are about the things that matter most. And that’s true not only of the initial police response to Ferguson, but also of the restrictions placed on many of the Occupy demonstrations, on some labor protests and in many other instances of political and religious dissent in recent years.

Ferguson does not have any easy solutions. But we need to begin by talking about the problems in a more honest and self-reflective way. We need to start having the tough conversations that many of us too often avoid out of fear, ignorance or inconvenience.

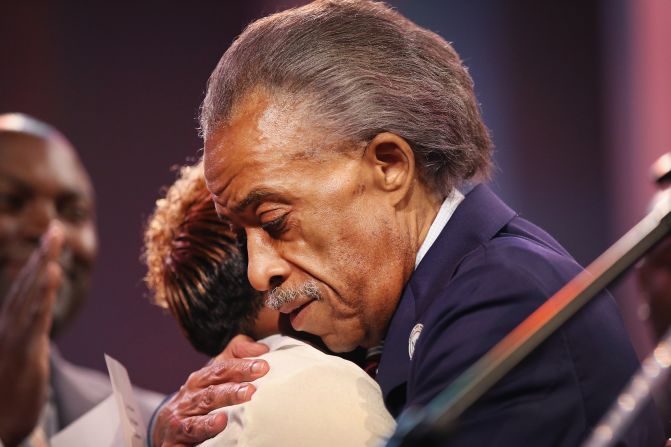

Some of us have been engaged in these conversations for a long time. But many of us, especially many people whose lives and neighborhoods and workplaces look a lot like mine, have not yet begun. Whether we’ve already been talking or are just about to start, we need to risk awkwardness and misunderstanding as we stumble toward dialogue. And we need to extend grace to one another as we take those risks.

But we can’t just talk. We need to be willing to share time and experiences that lead to friendships, not just conversation partners.

We might look to Ferguson to see what else must come next: learning about the issues, better supporting local businesses and nonprofits, expanding voter registration and voter education, monitoring local courtrooms and bureaucrats and holding accountable those officials who have used their power for harm rather than for good.

We can do these things after the cameras go away and where the cameras have never been.

We may not all put bodies on the line for the largely peaceful demonstrations. But we can put them on the line in the months and years to come – by choosing to engage in the slow and difficult work of restoring communities.

We owe at least that much to Ferguson and to all the Fergusons across our country.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine