Story highlights

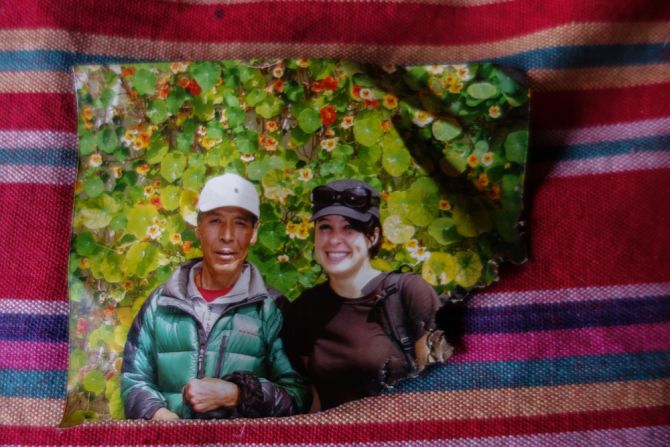

Ang Tshiring, 57, was among the 16 killed in this year's Mount Everest avalanche

In Nepal's Thame Valley, villagers have few employment options other than to work in the climbing industry

For families of deceased, sadness now eclipsed by spiritual duty

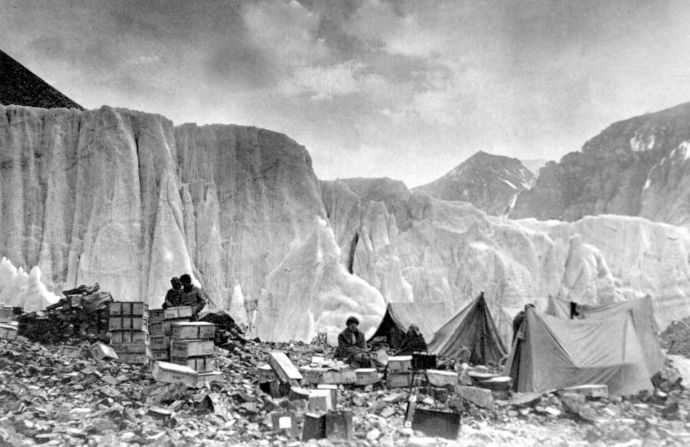

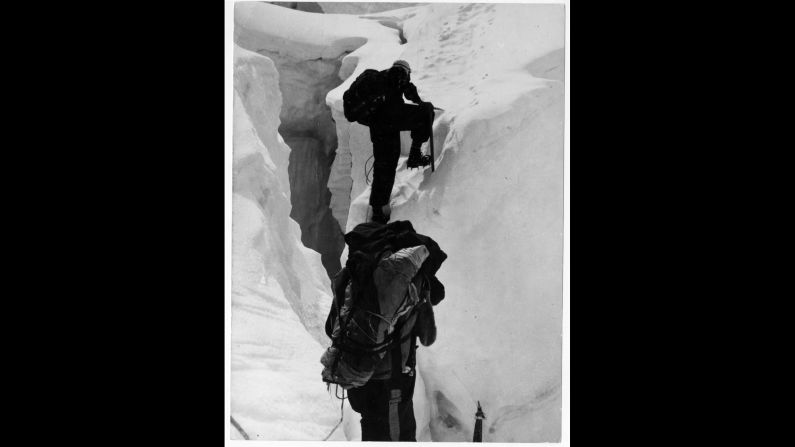

Pemba Sherpa had already reached Camp 1 on Mount Everest when he heard the loud and chilling bang of the avalanche.

He knew his father was behind him on the Khumbu Icefall and ran down the mountain, only to find the devastation of ice, snow and baggage scattered everywhere.

“I thought he abandoned his load and ran to safety,” he tells me, almost whispering.

“But I could not find him amid the commotion at base camp. Then I saw the helicopters, with the bodies on the suspended ropes, and I knew I lost my dad.”

Ang Tshiring’s body was taken to Lukla, a tourist town where most who embark on a trip to Everest Base Camp start out.

From there, Pemba and his brother carried him home themselves on foot, a trek that took seven hours along the mountain trail.

Unforgiving land of few opportunities

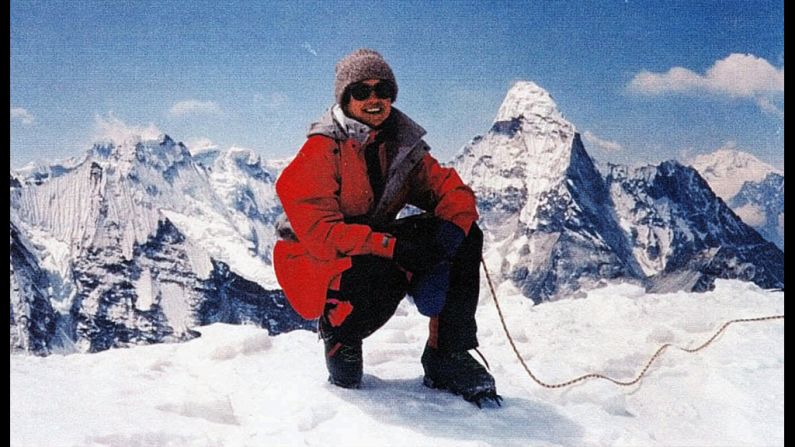

Ang Tshiring, 57, was a high altitude cook.

For the past 15 years, during the climbing season, he spent one month at Everest Base Camp and one month at Camp 2, at 6,100 meters.

Two months to earn $1,500, meant to last the year.

Ang Tshiring was famous for always showing happiness.

Climbers who knew him remember him as a funny man, laughing and joking all the time, never angry, always kind.

His son Pemba, 37, lives with the family in Thamo, a small village of 50 souls located in the Thame Valley in the Khumbu, where the country’s greatest ethnic Sherpa climbers live, well off the beaten track of Nepal’s Everest Base Camp trail.

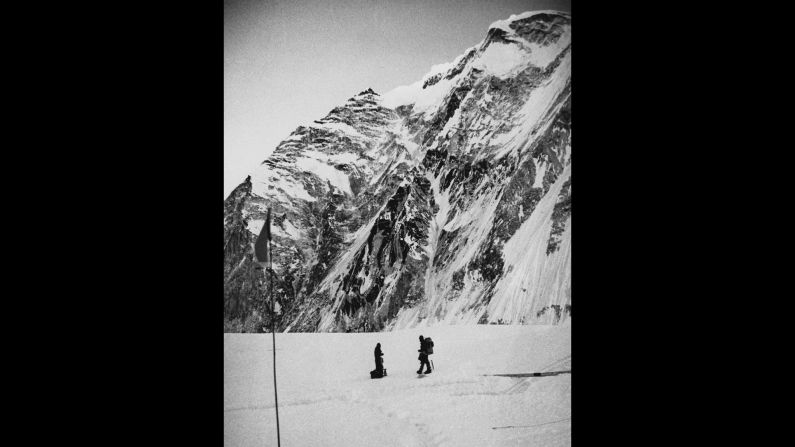

The Thame Valley suffered the biggest loss of life from April’s Everest tragedy that killed 13 guides (another three are still missing and presumed dead), the deadliest accident in the history of the world’s highest peak.

Here, every man, if not in school or too old, is involved in climbing expeditions.

They have few other choices.

Little grows but the odd patch of potatoes.

Few tourists pass by and yak herding is an insufficient way to make a living.

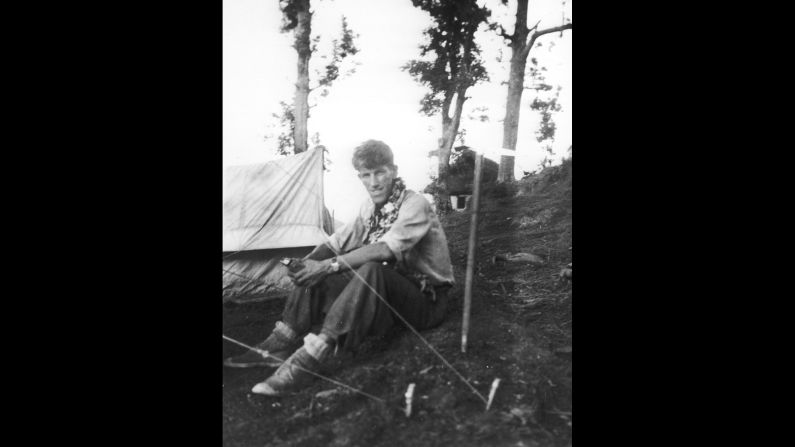

Cut off from the economic tourism opportunities that the rest of Nepal’s Kumbhu region enjoys, uncontaminated by progress, the Thame Valley retains the atmosphere of ancient Himalaya – which for centuries nurtured the Western utopian dream that a secret land of happiness may exist somewhere among the impenetrable snow-capped mountains.

The villages are marked by the vernacular architecture of slate-roofed houses.

Traders still cross the perilous high passes into Tibet with their cargo of salt and wool as they’ve done since ancient times.

Exploring Mount Everest

There’s an abundance of pagodas, monasteries, stone walls carved with mantras, wheels containing prayer scrolls and sacred shrines.

Thousands of colorful flags flutter in clusters, offering prayers to be carried along by the wind.

Everest avalanche: American climber recounts how Sherpa saved his life

A time to earn merit, not mourn

In Ang Tshiring’s home, feelings of sadness are eclipsed by spiritual duty.

“All that matters now are the puja,” says Ang Riku, his widow, referring to a series of prayers and rituals.

Her focus is on directing special prayers aimed at purifying and earning merit for Ang Tshiring’s spirit.

Nothing else holds relevance for her – not the political demands of the Sherpas, nor the discussions raging on social media worldwide, nor whether someone will climb Everest from the Nepal side of the mountain this year.

She’s silencing her mourning and sorrow to give all of herself for the benefit of Ang Tshiring.

The Sherpa follow one of the Tibetan sects of Buddhism, Nyingmapa, and believe that 49 days after Ang Tshiring’s death, his next life is determined and he may reborn.

Ang Riku is concerned.

She says accidental deaths are a bad way to go.

It means Ang Tshiring’s consciousness was in confusion when he died, and that affects his afterlife and rebirth.

The more people involved in the prayers, the better the chances of a superior reincarnation.

Ang Riku and Ang Tshiring’s private quarters have been transformed into a prayer room, and we all sleep together on the floor of the main hall.

Early in the morning, Ang Riku and I plan to go to the three isolated monasteries of Ginupa, Charok and Laudo, located high on the steep hills above Thamo.

Immersed in nature, they’re a retreat for ascetics and much revered by local communities.

On the kitchen table are several kilograms of rice, three bottles of Coke, a few pats of butter and sugar.

Her son, Pemba, has already left for Namche Bazar to meet the management of the company his father worked for to discuss what support they can offer.

“You are my porter,” Ang Riku says, bursting into a laugh, and I’m glad that she finds my presence amusing.

High cost of devotion

Ang Riku climbs the yak trails with determination, stopping every few minutes to catch her breath.

We pass through forests of juniper, continuously climbing until we reach the clouds and the monasteries hidden in them.

At each gompa (monastery), the same ritual takes place.

The lama (priest) offers us butter or milk tea and food.

We politely decline, but the lama insists and we accept.

We barely empty half of our bowls when the lama comes to fill them again.

We decline, he insists, we accept again.

Then Ang Riku offers money for the lama to perform the puja.

The lama declines, she insists, he accepts.

This display of generosity is a fundamental aspect that governs the relationship of the Sherpas.

Next, Ang Riku prepares a copper plate full of rice, the equivalent of $30, and a ceremonial white scarf that the lama will use for the prayers.

We pay our respects in the monastery’s prayer room.

Before leaving, the lama puts the ceremonial scarf around Ang Riku’s neck.

It’s an emotional moment, the only time Ang Riku lets her emotions overtake her.

She cries, holding the hands of the lama, abandoning herself in his support.

After six or seven bowls of noodles and a dozen teas, we head back home.

Ang Riku’s face is relaxed.

She’s carried out important deeds for her husband.

But today was just a small part of the funeral rites.

Ang Riku also sends bags with salt, butter, rice and money to 500 families in the valley, so they’ll recite prayers for Ang Tshiring.

She says she sent similar bags to many monasteries in the Kumbhu and in special holy places as far as India.

The cost of such devotion is high.

To confirm a day of puja in a large monastery costs $1,300.

The total expenditure will be upward of $10,000, significantly more than the life insurance that the government pledged after many protests by the Sherpas.

Ang Riku says she had to ask for a loan at the market at an interest rate of 25% per year – she doesn’t have the collateral to borrow from banks.

Climbers head home as Everest Sherpas refuse to work

“I wonder if I will come back alive?”

Although the world regards them as high altitude guides and porters, most Sherpas don’t want to be mountain climbers on Everest.

Better jobs are available for many in the other valleys of the Khumbu that cater to trekking tourists.

But here in the Thame Valley, there aren’t many options.

“Every time I go on a climbing expedition, I wonder if I will come back alive,” says Pemba.

“I feel sad, but I have to do this job for my family. I’ve summited Everest 14 times and I’ve always brought a photograph of my family with me.”

Though more catastrophic than usual, this year’s tragedy was no great surprise for those in the Thame Valley, who have become familiar the loss of life that almost always occurs in April and May.

The only difference, Pemba tells me, is that “this year was particularly unlucky.”

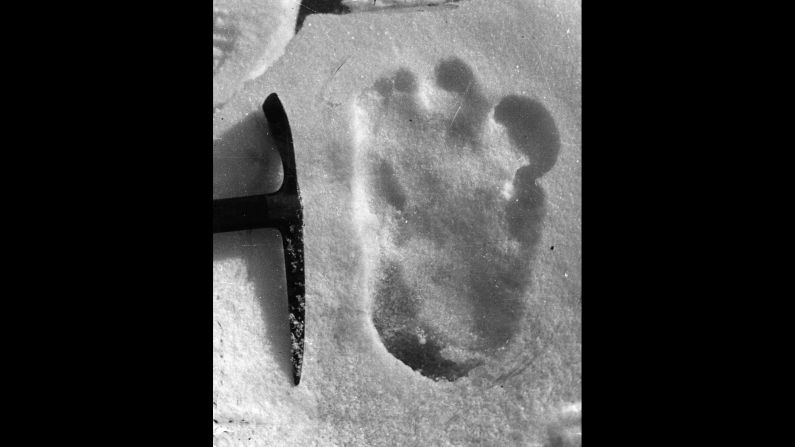

The Sherpas’ approach to religion includes an animist tradition that holds that mountains and other natural features are the abodes of deities that can make men suffer if they fail to respect them.

I offer a puja in the monastery for Ang Tshiring in the afternoon and ask Lopsang, a young monk who says he escaped from Tibet, the reason behind the bad luck.

“I don’t know if the god of the mountain was angry – maybe it was global warming,” the monk tells me, smiling.

The Sherpas climb for their children; they see education as an opportunity for them to have a better life.

Nima, Ang Tshiring’s 17-year-old daughter, attends private school in Kathmandu.

Back in the family home, we clean the brass cups to make new butter lamps, which need to be lit in the prayer room in the house throughout the 49-day funeral period.

“Papi is looking at us and he must be laughing hard, watching his daughter and a foreigner cleaning lamps for him,” Nima says.

Putting the butter in a pot to melt, Nima says her father told her about the difficulties of being a Sherpa, and the promise he made that she would never have to experience them.

Soon, Pemba arrives back from Namche Baazar, bringing good news.

He says Alpine Ascent, the company that he, his father and his brother work for, have committed to help with the two most important issues for the Sherpa of the Thame Valley: they’ll contribute significant funds to pay for the pujas for Ang Tshiring and they’ll pay for Nima’s education until she graduates.

Pemba places a spoonful of tsampa, the roasted barley flour his father loved, on hot coals on the windowsill, as food for his spirit.

In the distance, Mount Tamserku radiates the yellow light of dusk, like it always did and always will.

Everest climbers, widower recount deadly traffic jam on top of the world

Andrea Oschetti is a Hong Kong-based freelance travel writer currently traveling through Nepal and Tibet.