Editor’s Note: CNN’s On the Road series brings you a greater insight into the history, customs and culture of Ghana. CNN explores the places, the people and the passions unique to this African nation.

Story highlights

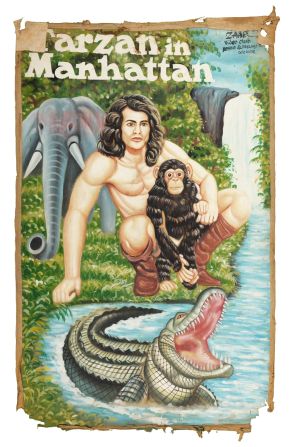

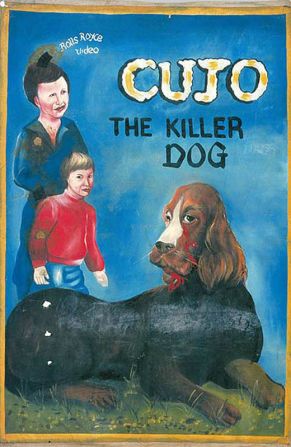

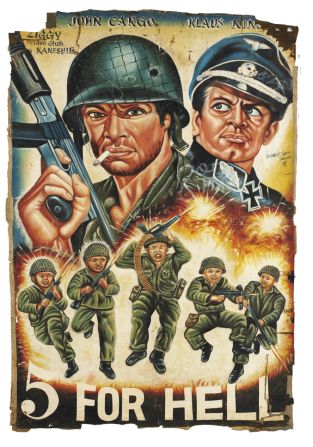

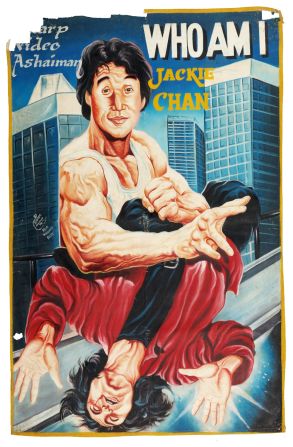

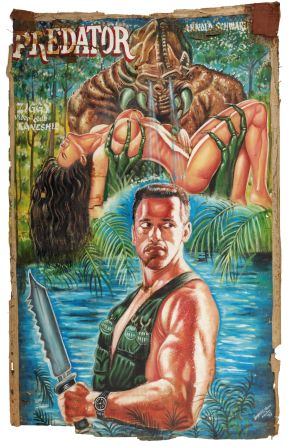

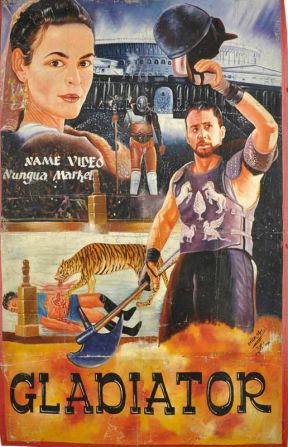

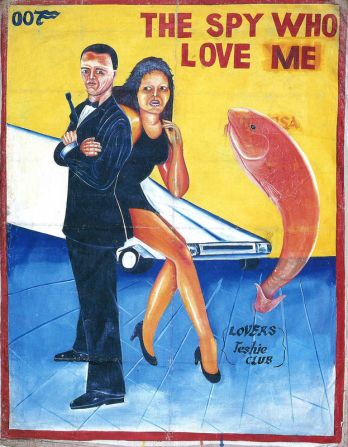

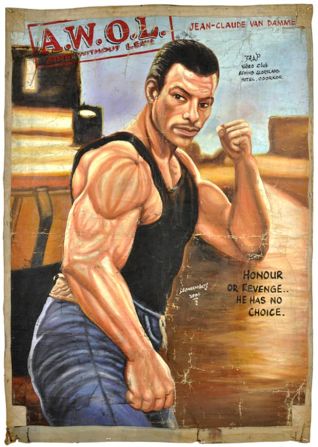

Hand-painted movie posters from '80 and '90s have become collectibles

Originally painted to attract people to local cinema clubs in Ghana

Most were painted on used flour sacks stitched together

Original artists continue to produce imagined versions of current films to feed growing art market

How would you design a movie poster for a Hollywood blockbuster you’d never seen, filled with characters you knew nothing about and actors you’d never heard of?

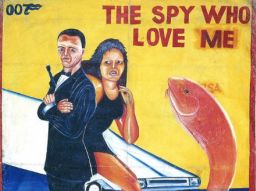

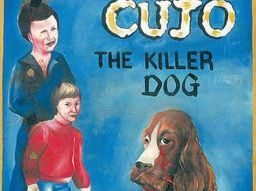

Would Jean-Claude Van Damme look like a surgical glove stuffed full of walnuts? Would Cujo the killer dog look like a guilty spaniel that’d devoured the cake at a child’s birthday party? Would James Bond have the stunned expression of a man who had just received a large electricity bill?

If your only brief was to pack a crowd into a mobile African cinema hall, you might also want to add some incidental aliens shooting laser beams from their eyes.

In Ghana – where the Golden Age of movie posters during the 1980s and 1990s produced these lurid, vibrant and outlandish originals – the movie poster may be a dying art form but it has since become big business.

Western collectors now pay thousands for prime examples of the genre and the artists who once churned out the posters to fill Ghana’s dilapidated cinema clubs are finding a new lease of life reproducing them for art aficionados.

Jeaurs Oka Afutu, 39, began painting the posters when he was 14 years old but now works from his home in Accra, Ghana, to produce them for art dealers, selling them for between $75 and $100 apiece.

Currently putting the finishing touches on a canvas cut from a flour sack, he’s producing a distinctively Ghanaian take on the biopic “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom.”

“Action and war works a lot … and women too: both actually,” Afutu told CNN, showing that Hollywood’s time-honored recipe of sex and violence is an international language.

“It all depends on what the audience prefers.”

Read more: Keeping Africa’s star of democracy shining

When he produced these originals for Ghana’s cinema clubs — often no more than rows of seats in the open air around a gas-powered generator and a TV set with a VCR — his job was to draw crowds.

To do this, he applied his imagination to the canvas, producing scenes that didn’t exist in the original film; placing dripping knives in the hands of zombie assassins or guns at the ready for various heroes who had no weapons in the actual film.

These surreal variations spiced up a whole generation of schlock-horror films that came out of Hong Kong, Hollywood, Bollywood, and its Nigerian equivalent Nollywood. As one critic remarked, the posters are often far better than the films.

African art dealer Ernie Wolfe, who first noticed the movie posters in 1990 while researching Ghana’s phenomenon of fantasy coffins, said that despite the untutored style of the posters, the artists knew exactly what effect they wanted to create.

“They are definitely very, very good artists and they paint exactly what they want,” said Wolfe who has written two books on the genre “Extreme Canvas” and “Extreme Canvas 2.”

“Having looked at hundreds of them, you become aware of their individual hand, their idiosyncrasies and their brush strokes.

“The ones that interest me the most are the ones before the tradition died in about 2000.”

Read more: Bamboo bikes turn around fortunes

Ghana’s economic development – combined with affordable technology that has brought home entertainment within the reach of many Ghanaians – put paid to the movie poster cottage industry.

While they’re still being made by some of the artists that produced them two decades ago, Wolfe explained, they’re now made as commodities for the art market.

“The best of the Golden Age movie posters – from the ’80s to the late ‘90s – are the ones where they just completely went out into the land where there are no rules,” he said. “It gave them an incredible freedom to be expressive.

“They made images that they knew would bring people in and no one was looking over their shoulder to tell them they couldn’t do anything.”

The only restriction, he said, was the size of the canvases which fell strictly into two versions: one side of a 50kg flour bag or two sides stitched together.

“Apart from that, there were no limits.”

He said the works also fall into the realm of art artifact where the evidence of their original purpose is also part of the narrative.

“The work patterns of their use; having been nailed up by their corners and splattered by mud from passing buses also tell a rich story about how they were utilized,” Wolfe said.

With rare vintage works fetching as much as $15,000 and Golden Age posters routinely going for between $1,500 and $3,000, a market in fakes has emerged.

Wolfe, however, remains sanguine.

“It’s possible to say they’re fakes but it’s also possible to say they’re a homage,” he said.

While the commoditized versions are still artworks in their own right, Wolfe said they occupy a different zone to the stark immediacy of the originals.

“There’s a big difference between those works that were produced for them, Ghanaians, and the ones that are produced for us (collectors).”

CNN’s On the Road series often carries sponsorship originating from the countries we profile. However CNN retains full editorial control over all of its reports. Read the policy