Editor’s Note: Neil Weare represents the plaintiffs in Tuaua v. United States, a case seeking citizenship rights for residents of American Samoa. He is president and founder of the We the People Project, an organization that works to achieve equal rights and representation for the nearly 5 million Americans living in U.S. territories and the District of Columbia. A graduate of Yale Law School, he grew up in the U.S. territory of Guam, and now lives in the District of Columbia. He competed for Guam in the 2004 Olympics in the 1,500-meter run.

Story highlights

Neil Weare: There's a compelling legal case for citizenship for American Samoa residents

He says the 14th Amendment provides citizenship for all people subject to the U.S.

Courts have disagreed on the matter, but Weare's lawsuit is pending in federal court

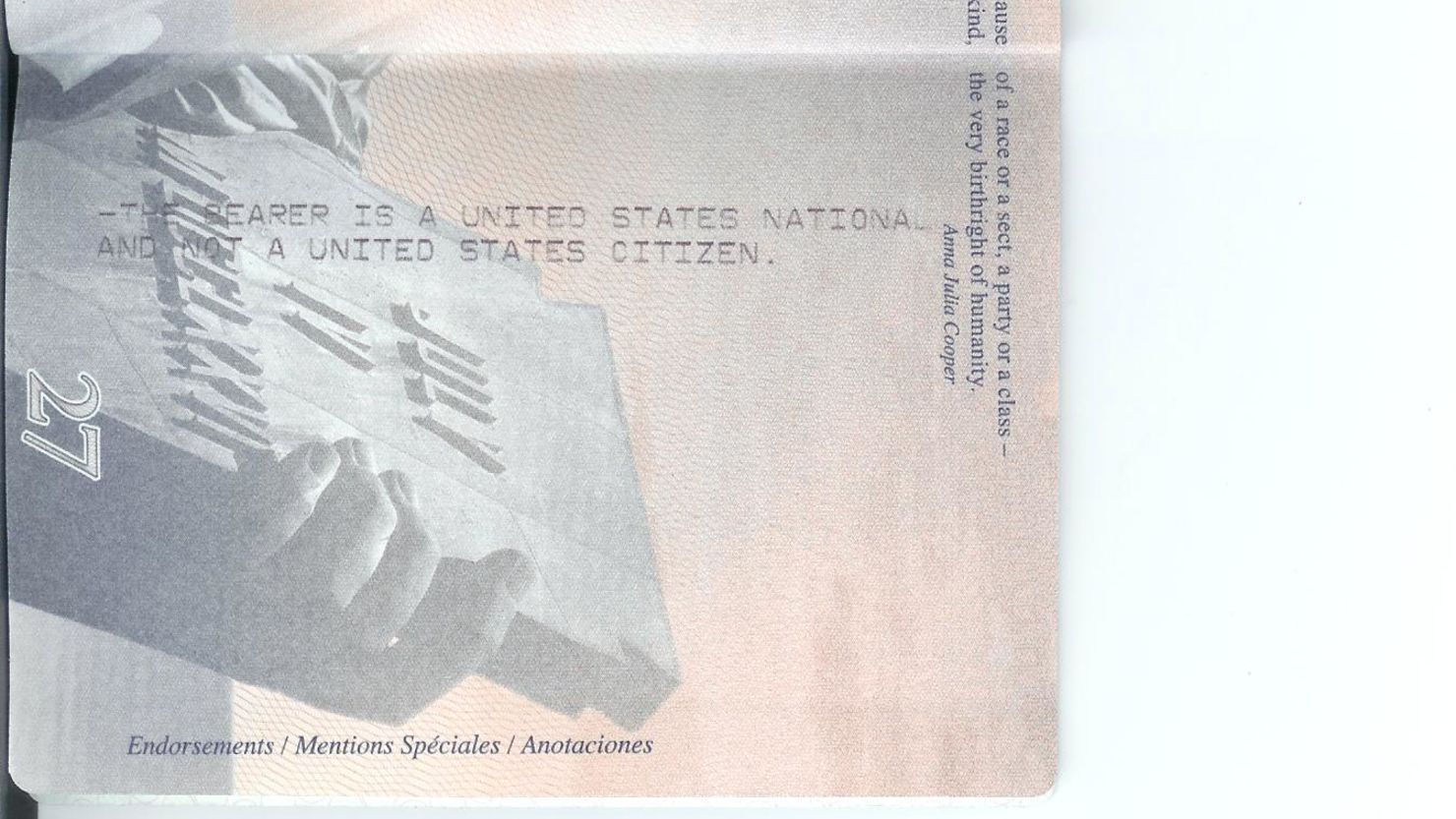

CNN Legal Analyst Danny Cevallos recently highlighted a fact that few in the United States are even aware of: Tens of thousands of Americans who hold U.S. passports are denied legal recognition as U.S. citizens. The reason? They happen to be born in the U.S. territory of American Samoa instead of somewhere else in the United States.

Cevallos gets the basic unfairness of it all right: “The United States laid claim to these eastern islands of a South Pacific archipelago in 1900, and since that time, American Samoans have served in the U.S. military, including the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.” But his conclusion that “citizenship for them is not a constitutional right” because “only Congress can choose to grant citizenship to territorial inhabitants” rests on an assumption that has no basis in the Constitution or any decision by the U.S. Supreme Court.

It is easy to see where this assumption comes from. After the United States acquired Puerto Rico and other territories in 1898 after the Spanish-American War, the Supreme Court decided a series of deeply divided and controversial cases known as the Insular Cases.

While none of these cases addressed constitutional issues relating to citizenship, Justice Henry Billings Brown wrote an opinion in Downes v. Bidwell that suggested, in passing, that citizenship was not a fundamental right in these newly acquired areas, which were populated by what he called “alien races.”

Although his opinion was not joined by a single other justice, it was good enough for those in Congress who thought birthright citizenship was not such a great idea for the inhabitants of these areas, who did not look like or speak like them.

The assumption that Congress controls citizenship in overseas territories has survived since, but not without disagreement in the lower courts.

Leneuoti Tuaua, the Samoan Federation of America, and several others born in American Samoa are challenging this faulty assumption in a federal lawsuit pending before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. They argue that so long as American Samoa is under the U.S. flag, with American Samoa’s sons and daughters fighting and dying to defend that flag, the U.S. Constitution guarantees them birthright citizenship, regardless of what Congress has said.

What does the Constitution itself say? The Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment – part of the Constitution since 1868 – states that “All persons born … in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States.”

The great Chief Justice John Marshall explained decades earlier that the Constitution used the phrase “the United States” as “the name given to our great republic, which is composed of states and territories.”

It is no surprise then that those who drafted the Citizenship Clause understood its guarantees to extend to U.S. territories, explaining that “the first section (of the 14th Amendment) refers to persons everywhere, whether in the states or in the territories or in the District of Columbia.” Just four years after the Citizenship Clause was ratified, the Supreme Court stated that the clause “put to rest” the notion that “those … who had been born and resided always in the District of Columbia or in the territories, though within the United States, were not citizens.”

This original understanding makes sense. The 14th Amendment was intended to overturn the Supreme Court’s infamous Dred Scott decision and put the question of citizenship by birth on all U.S. soil beyond Congress’ power to deny. In 1868, nearly half of all land in the United States was in a U.S. territory. An amendment that failed to guarantee citizenship in U.S. territories would not have been much of an amendment at all.

Birthright citizenship remains a hotly debated topic. But there is a remarkable cross-ideological consensus among legal scholars about what exactly the Constitution guarantees when it comes to birthright citizenship.

Former U.S. Solicitor General Ted Olson, who represented President Bush in Bush v. Gore, and Harvard Law Professor Laurence Tribe, a renowned liberal scholar, argued in a 2008 joint memo that Sen. John McCain was eligible to run for president based solely on his place of birth: the Panama Canal Zone, a former U.S. territory.

Olson and Tribe explained that “birth on soil that is under the sovereignty of the United States, but not within a state” satisfies the requirement for being a ” ‘natural born’ citizen,” in light of “the well-established principle that ‘natural born’ citizenship includes birth within the territory and allegiance of the United States.”

President Clinton’s Solicitor General Walter Dellinger and former Texas Solicitor General James Ho have echoed similar views on the geographic scope of birthright citizenship.

What the Insular Cases mean for U.S. territories today also remains hotly debated. On Wednesday the Harvard Law School is holding a conference titled “Reconsidering the Insular Cases,” with federal Circuit Judge Juan Torruella delivering the keynote address “The Insular Cases: A Declaration of Their Bankruptcy.” Torruella has long compared the Insular Cases to Plessy v. Ferguson, criticizing the Insular Cases as establishing a race-based doctrine of “separate and unequal” status for residents of overseas U.S. territories.

In 2008, the Supreme Court also expressed skepticism of the idea that Congress has the power to deny constitutional rights in current U.S. territories, stating that “it may well be that over time the ties between the United States and any of its unincorporated territories strengthen in ways that are of constitutional significance.” The court went on to explain that “the Constitution grants Congress and the president the power to acquire, dispose of, and govern territory, not the power to decide when and where its terms apply.”

Although the Constitution grants Congress broad powers in U.S. territories, one that it clearly withholds is the power to rewrite the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of birthright citizenship. Denying citizenship in American Samoa is not just unfair, it’s unconstitutional.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Neil Weare.