Story highlights

Sunday, February 9, marks 50 years since Beatles appeared on "Ed Sullivan Show"

Telecast was watched by 73 million, changed lives

One person who watched is producing Grammy tribute; another bought archive

Show remains one of the rare collective experiences of many Americans

Two of them watched on television. One of them was on television. And one of them was helping make television.

Andrew Solt, Ken Ehrlich, Debra Supnik and Vince Calandra were all part of the massive audience who watched The Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Solt and Ehrlich were part of the then-record 73 million people who gathered around CBS that Sunday evening, February 9, 1964. Supnik was in the studio audience, one of 728 lucky souls. And Calandra, part of the Sullivan production staff, watched from offstage – when he wasn’t hustling to keep the show going.

Fifty years have passed since that day. Since then, the cultural world has splintered into countless pieces. The Sullivan show was one of the last vestiges of a time before our atomized society, points out pop culture expert Robert Thompson.

“In many ways, (the Sullivan anniversary) is not just about a very, very successful group, but the way Americans consumed culture and the way in which we were all glued together,” says Thompson, director of the Bleier Center for Television & Popular Culture at Syracuse University.

Beatles + Sullivan = Revolution: Why Beatlemania could never happen today

Solt, Ehrlich, Supnik and Calandra have also taken their lives in various directions. But a connection to that evening has bound them together – in ways unimaginable in 1964. Here are their stories.

The witness

It’s a famous photograph: three of The Beatles – John Lennon, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr – playing a Sullivan rehearsal with an unfamiliar fourth figure, a smiling guy in a Beatle wig awkwardly holding a guitar.

That would be Vince Calandra.

Calandra, then 29, was a production assistant on the Sullivan show. He was standing in for George Harrison because the guitarist was laid up with a throat problem.

The moment has only gotten richer over the years, he says.

“I wasn’t just this Sicilian kid from New York who put this Beatle wig on. I was part of history,” he says. “Who on the planet stood on stage and actually had The Beatles singing their songs, standing there like a statue, holding a guitar that’s probably worth now a million and a half dollars?”

He was there for the whole crazy weekend.

5 things to know about Beatlemania

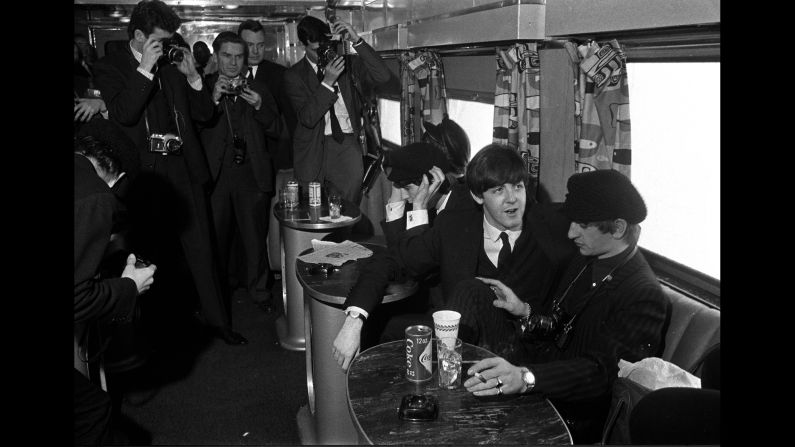

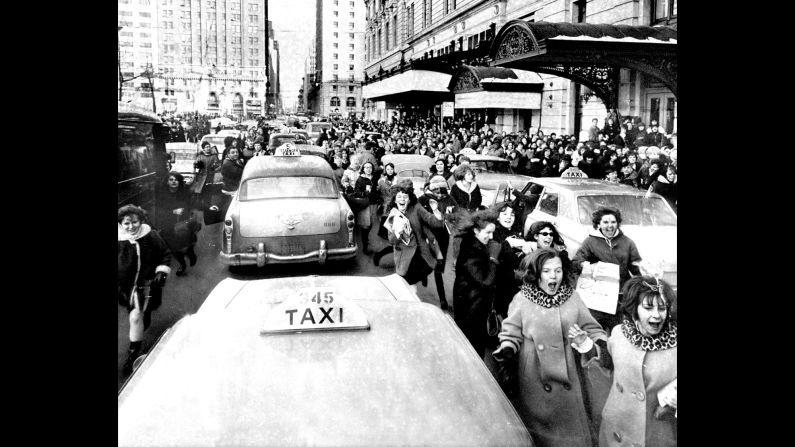

The Beatles arrived in New York on Friday, February 7, and John F. Kennedy Airport was in chaos: 3,000 screaming fans, police protection, a packed press conference. Calandra says Beatles roadie Mal Evans asked him if this happened every time a rock band appeared on Sullivan.

“I said, what? The Charge of the Light Brigade with 20 mounted horsemen going down Broadway chasing after a limousine?” he says.

Security, in fact, was a priority. Studio employees wore special badges. Police barriers blocked off the streets around the theater.

In the midst of it all, Calandra was impressed by The Beatles’ professionalism. After running through their set during a rehearsal, they asked to visit the control room to make sure the audio levels sounded good on playback. That was a first, says Calandra.

“They were very polite, not demanding,” he recalls. “They were 21 or 22, going on 40.”

The actual show passed in a blur. Calandra describes the Sullivan staff as “like a commando squad. There were very few of us, and we all protected each other.” His title of “assistant” is an understatement by today’s standards: Calandra timed the acts, ordered props, marked the floor, edited film, cleared music – jobs that, today, would be handled by a whole staff. The Beatles weren’t the only act on the show, and there was plenty to do.

Calandra, who will turn 80 in April, went on to a long career as a producer and executive for several television shows and the American Film Institute. He crossed paths with The Beatles again, notably in 1965 when he helped with arrangements for the group’s Shea Stadium show.

But those Sullivan shows, he says, were special.

A week later, after The Beatles’ second show in Florida, Sullivan threw a party. It was a small group, Calandra says – the band, their inner circle, a few journalists and some Sullivan staffers. Everybody was happy but exhausted.

“It kind of got a little bit emotional,” Calandra says. “At the end of the night, (Ringo) had this funny look on his face. He just sat there at the table, and he said, ‘This is the best it’s ever going to be. How do you top this?’

“And you know,” Calandra says, “he was wrong.”

The fan

The album sticker said, “If you love The Beatles, why don’t you join our fan club?”

The album was “Please Please Me,” The Beatles’ first UK release, and Debbie Supnik – then 12-year-old Debbie Gendler of Oakland, New Jersey – liked the idea.

“I thought these were the cutest people I’d ever seen in my life. I fell immediately in love,” she recalls. She played the album for all her friends and wrote a letter to England about joining the fan club.

There was a catch. It was April 1963 and nobody in the United States knew who The Beatles were. Supnik’s letter went unanswered.

Until October, when she received a telegram. The Beatles were coming to New York in 1964, and they were looking for fans to welcome them. Supnik convinced her father to drive her into the city to meet with the band’s representatives.

Supnik got some bad news: They wanted someone a little older to run the fan club. However, she got a nice consolation prize: a ticket to attend the February 9 “Ed Sullivan Show.”

The show, she says, was something else. Her mother drove into Manhattan and parked blocks away, thanks to the security. Supnik held her ticket close. Her mother helped with skeptical police officers.

“You needed an adult, because they wouldn’t believe any kids at all,” she recalls.

At the studio, she found her seat. Behind her, a girl screamed and screamed and screamed. Supnik tried to stay calm.

“It was really difficult to do. You had to start screaming,” she says. “Sitting through the other acts was probably the most difficult thing.”

Only future Monkee Davy Jones, part of the “Oliver!” cast, was “tolerated,” she says, because “he had an accent.”

But she brushes off a memory of Sullivan getting a little upset because he believed the audience was impolite.

“We just couldn’t handle anyone else. How could you? It’s The Beatles there!”

Supnik soon started a fan club chapter in New Jersey. In 1965, she met the band at the invitation of Beatles manager Brian Epstein; two years after that, she visited England and met Harrison’s parents, McCartney’s father and some of the London-based staff.

Today, Supnik is a Los Angeles-based TV producer and consultant, currently working on a Hallmark Channel show called “Home and Family.” But when she talks about The Beatles and Sullivan, what emerges is the teenage girl who couldn’t believe her good fortune.

Neither, it turns out, could some of her friends.

That night in February 1964, after the show, Supnik remembers barely being able to contain herself. The next day, back at school, she spoke about the exciting evening.

Years later, one of Supnik’s friends was chatting with Supnik’s mother, who’d waited up for her in Manhattan.

“The girl said to my mom, ‘You know, Mrs. Gendler, I’ve waited all these years. Was that really true? Did Debbie really go to ‘The Ed Sullivan Show’?” Supnik says.

“And my mother said, ‘Yes. I took her.’ And she said, ‘We all just always found it so hard to believe.’ “

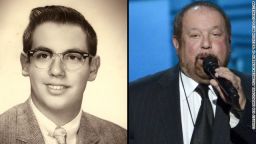

The producer

Ken Ehrlich remembers the moment as if it were yesterday.

“I was in Mrs. Finsterwald’s parlor, in Athens, Ohio, at Ohio University, with my then-girlfriend, and it was – to me – everything that has become the legend,” he says of watching the Sullivan broadcast. It’s late January and he’s chatting over the phone from Los Angeles’ Staples Center, where he’s preparing to produce the Grammy Awards. Behind him, one can faintly make out the organ from “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.”

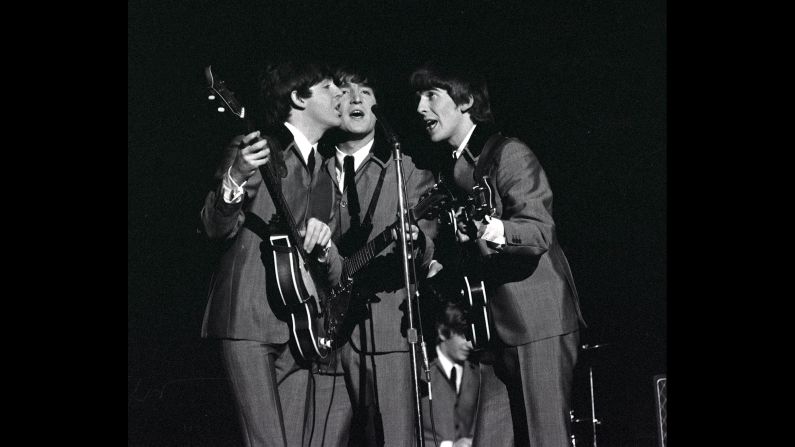

“It was really mind-blowing,” says Ehrlich, then 22 and a senior in college. “We had heard of them, but nobody had ever seen them. It was before VCRs – it was before color – and we were sitting there, and all of a sudden these kids came on. They didn’t really look like us, but they looked like we wanted to look, and they sang these great songs. They sounded familiar but they sounded different.”

Fifty years later, Ehrlich is going to return the favor. He’s producing “The Night That Changed America: A Grammy Salute to The Beatles,” which will air in Ed Sullivan’s old time slot on Sunday night. Among the bands paying tribute: the Foo Fighters, Stevie Wonder, Lady Antebellum and a reunited Eurythmics.

“I purposely went after artists who I knew had a feel for The Beatles and their music,” he says.

Ehrlich has a lot of experience with producing music for television. He’s overseen the Grammys since the early ’80s; he’s also done variety shows, specials, a season of “Fame” and several years of the old PBS performance show “Soundstage.” He never considered a career in the music industry, though; his five decades have been in either public relations or television.

But The Beatles, he adds, have always been a presence in his life. Both Ringo and Paul have appeared on his Grammy telecasts – as they did this year – and Beatles music has animated Ehrlich productions through the years.

They were heard at last year’s Ehrlich-produced Emmy Awards in a segment that stressed how The Beatles’ Sullivan appearance helped people overcome the grief of the Kennedy assassination.

“We tried to make the point that (the Sullivan show), coming 2½ months after the Kennedy assassination, marked a turning point, not just in our cultural experience, but in our lives. All of a sudden it was OK to watch teenage girls scream and scream along with them – and to be happy,” Ehrlich says.

So much can be traced back to that evening at Mrs. Finsterwald’s. Indeed, he says, The Beatles were almost enough to make him change livelihoods.

It was 1967, and Beatles manager Brian Epstein had just died. The Beatles were said to be in the market for someone to manage Apple, their new company, and Ehrlich – then a brash 25-year-old Chicago PR man – decided he was perfect for the job.

“In my naive stupor, I actually sent a letter to Apple suggesting I would be qualified to run The Beatles empire,” he chuckles. “I never got an answer.”

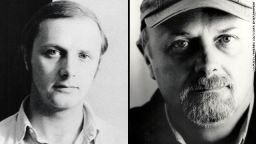

The guardian

Andrew Solt was determined to watch The Beatles.

He was 16 and a student at a Los Angeles-area weekday boarding school, which meant that he and his friends were home for the weekends but generally returned to the school on Sunday evenings. But this time there was a catch.

“We said to the teachers, if they didn’t allow us to see The Beatles on Sullivan we wouldn’t come back on Sunday evening like we always did,” he recalls. “They said, we’ll figure out something.”

The students usually didn’t have access to a television, but one was located and the rest, he says, “was magic.”

“We loved the music and had to see The Beatles,” he says. “Nobody had really seen them walk and talk and move. We had seen the stills on the covers, but no animated activity.”

Today, Solt owns that broadcast – and the rest of the Sullivan archive, all 1,050 hours of it. If people want to use The Beatles on Sullivan in a film or documentary, they have to make arrangements with Solt’s company, SOFA Entertainment.

In a way, his life has come full circle.

He was a huge music fan and thought about going into the business. But he became intrigued with documentary filmmaking, and within two years of leaving UCLA he was working on an Elvis Presley documentary. It was the first of many music-related projects he would do, eventually overseeing several himself, including “This Is Elvis” (1981) and “Imagine: John Lennon” (1988).

“The music synched up with the documentaries and that happened to me, on and off, over the years,” he says.

Inevitably, creating music documentaries meant coming into contact with the Ed Sullivan archive, which featured dozens of the top acts of the ’50s and ‘60s. Solt found himself using the material for works on Presley, the Rolling Stones and a history of rock ‘n’ roll.

One thing led to another and, in 1990, he offered to buy the entire library. Solt can’t reveal the price, but says, “suffice it to say, it was millions of dollars – and I was borrowing it all.”

It also meant that he became the keeper of more than two decades of priceless Americana.

In the years since, Solt has handled the investment wisely. The Sullivan archive has been digitally mastered; after 9/11, copies were made for the Library of Congress and “a salt mine in Kansas” for safekeeping, Solt says. SOFA has issued several Sullivan collections, including a box set of The Beatles shows as originally telecast, commercials and all.

Indeed, Solt can’t help but marvel at the influence of those Beatles episodes.

“It’s one of the most important moments in the history of television,” he says. “It’s in black-and-white, but it’s almost as if they’re appearing in color and the rest of the show is in black-and-white.”

Does he feel a burden, owning such an important piece of history?

Solt chuckles.

“I love it, but it’s a bit like an elephant that’s in the building,” he admits. “You kind of have to feed it in the morning and clean up after it in the evening and then turn the lights off. It’s a living and breathing thing.”

But, he adds, he wouldn’t have it any other way for a 16-year-old, who – once upon a time – had his eyes opened while watching a borrowed television.

“It is really a gift, and I’m very fortunate to be entrusted with it.”