Story highlights

Hiroo Onoda wouldn't accept Japan's World War II defeat until 1974

He stayed in the jungle on the Philippines island where he had been deployed

His former commanding officer had to travel to the island to persuade him to give up

Onoda died of pneumonia in a Tokyo hospital Thursday, a collegue says

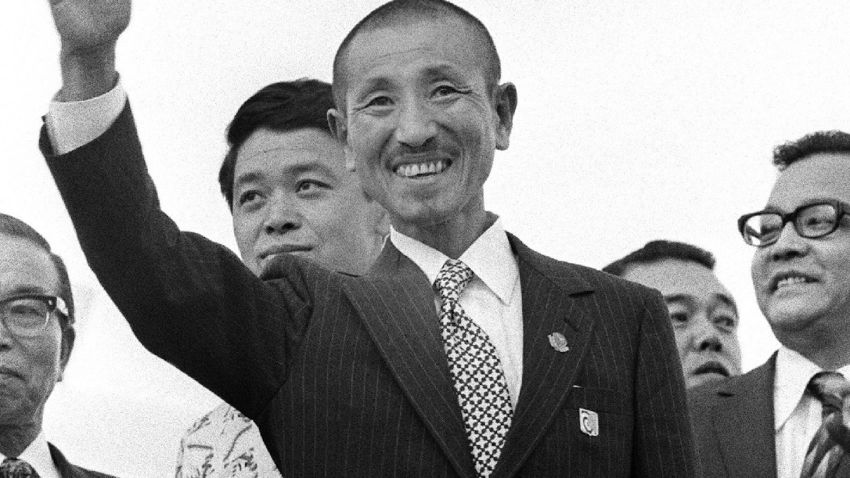

A Japanese soldier who hunkered down in the jungles of the Philippines for nearly three decades, refusing to believe that World War II had ended, has died in Tokyo. Hiroo Onoda was 91 years old.

In 1944, Onoda was sent to the small island of Lubang in the western Philippines to spy on U.S. forces in the area. Allied forces defeated the Japanese imperial army in the Philippines in the latter stages of the war, but Onoda, a lieutenant, evaded capture. While most of the Japanese troops on the island withdrew or surrendered in the face of oncoming American forces, Onoda and a few fellow holdouts hid in the jungles, dismissing messages saying the war was over.

For 29 years, he survived on food gathered from the jungle or stolen from local farmers.

After losing his comrades to various circumstances, Onoda was eventually persuaded to come out of hiding in 1974.

His former commanding officer traveled to Lubang to see him and tell him he was released from his military duties.

In his battered old army uniform, Onoda handed over his sword, nearly 30 years after Japan surrendered..

“Every Japanese soldier was prepared for death, but as an intelligence officer I was ordered to conduct guerrilla warfare and not to die,” Onoda told CNN affiliate, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. “I had to follow my orders as I was a soldier.”

He returned to Japan, where he received a hero’s welcome, a figure from a different era emerging into post-war modernity.

But anger remained in the Philippines, where he was blamed for multiple killings.

The Philippines government pardoned him. But when he returned to Lubang in 1996, relatives of people he was accused of killing gathered to demand compensation.

After his return to Japan, he moved to Brazil in 1975 and set up a cattle ranch.

“Japan’s philosophy and ideas changed dramatically after World War II,” Onoda told ABC. “That philosophy clashed with mine so I went to live in Brazil.”

In 1984, he set up an organization, Onoda Shizenjyuku, to train young Japanese in the survival and camping skills he had acquired during his decades in Lubang’s jungles.

His adventures are detailed in his book “No Surrender: My Thirty-year War.” The Japan Times excerpted some of the book’s highlights in 2007.

Here is a sample:

– “Men should never compete with women. If they do, the guys will always lose. That is because women have a lot more endurance. My mother said that, and she was so right.”

– “If you have some thorns in your back, somebody needs to pull them out for you. We need buddies. The sense of belonging is born in the family and later includes friends, neighbors, community and country. That is why the idea of a nation is really important.”

– “Life is not fair and people are not equal. Some people eat better than others.”

– “Once you have burned your tongue on hot miso soup, you even blow on the cold sushi. This is how the Japanese government now behaves toward the U.S. and other nations.”

Onoda was born in March 1922 in Wakayama, western Japan, according to his organization. He was raised in a family with six siblings in a village near the ocean.

READ: (1996) Former WWII soldier visits his Philippine hideout

Hiroyasu Miwa, a staff member of the organization that Onodo started in 1984, said Onodo died of pneumonia Thursday afternoon at St. Luke’s Hospital in Tokyo. He had been sick since December.

Ever the faithful soldier, Onoda did not regret the time he had lost.

“I became an officer and I received an order,” Onodo told ABC. “If I could not carry it out, I would feel shame. I am very competitive.”

CNN’s Yoko Wakatsuki reported from Tokyo and Jethro Mullen reported and wrote from Hong Kong. CNN’s Junko Ogura contributed to this report.