Editor’s Note: Lisa-ann Gershwin has been researching jellyfish more than 20 years and discovered more than 180 new species, including 16 that are potentially lethal. In 1998, she was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship to study jellyfish blooms and fossil jellyfish in Australia. Lisa is the director of the Australian Marine Stinger Advisory Services, and the author of “Stung! On Jellyfish Blooms and the Future of the Ocean” (May 2013, University of Chicago Press). She is based in Hobart, Tasmania.

Story highlights

Lisa-ann Gershwin: Jellyfish taking over vulnerable seas, displacing other creatures

She says jellyfish can kill off fish-sustaining krill that's harvested for omega-3 supplements

Gershwin: Jellyfish thrive as oceans get warmer; they eat the eggs and larvae of fish

Gershwin: We need to make industry stop polluting water and prevent global warming

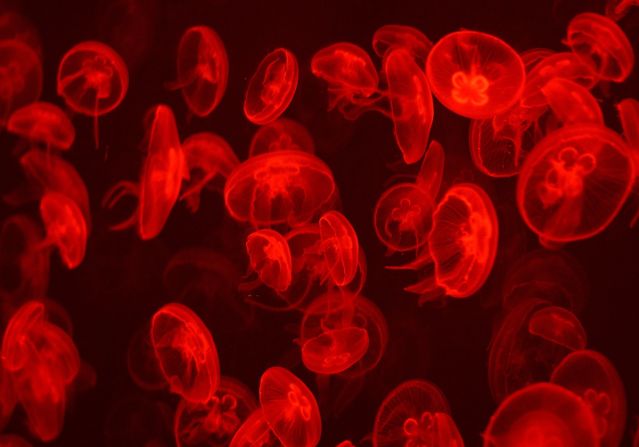

“Ouch!” is what most of us think when we think of jellyfish. They sting. They’re slimy and they have no brains. So who would’ve predicted that the lowly jellyfish could emerge from the shadows as a destroyer of fisheries and ecosystems and even as a threat to penguins and whales.

Far down in Antarctica – the last pristine wilderness, some might say – the balance is shifting from krill to jellyfish. In this harsh land, just about everything bigger than a krill eats krill: whales, seabirds, fish and penguins.

But krill are disappearing, thanks to us and the jellyfish. We fish out vast amounts of krill for our omega-3 supplements; the jellyfish eat vast quantities of plankton, leaving little for the krill to eat.

All over the world, from the Bering Sea to the Sea of Japan, from the Mediterranean to the Gulf of Mexico, from China to the Chesapeake, from the Black Sea to the Baltic to the Benguela off Namibia, any place oceans are in trouble, jellyfish are taking over. Jellyfish do well in warmer waters. Our carbon dioxide emissions are both warming the water and causing it to become corrosive. Warmer water – even a fraction of a degree – holds less oxygen than cooler water and shifts the balance of who survives and who perishes.

News: Jellyfish taking over ocean, experts warn

A strange type of jellyfish-like creature called a salp is particularly taking advantage. Salps are surely one of the world’s most bizarre critters. They can grow 10% of their body length per hour and go through two generations in a day. They are more closely related to humans than to most other types of jellyfish, though they certainly don’t look like it. Their bodies look like clear, gelatinous barrels. Salps don’t sting, but they do their damage in their staggering numbers. Ask the operators of Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant on the coast of central California.

In April 2012, Diablo was plunged into emergency shutdown because of salps clogging up the seawater intake pipes for the cooling system. This might seem freakish, but jellyfish have caused many dozens of such shutdowns at nuclear power plants, coal-fired power plants, desalination plants – pretty much any type of industry that draws seawater. Even seawater-cooled data centers such as Google’s Finnish facility are at risk.

Different types of jellyfish have caused mass fish kills at salmon farms all over the world. Ireland, Scotland, Chile, Australia, New Zealand… you name it. If salmon are being farmed, you can bet there are terrible jellyfish problems.

Jellyfish have also taken over Lurefjorden, one of Norway’s beautiful fjords and previously one of its best fishing spots. There is nary a fish to be found. Recently, two more fjords have also become colonized by jellyfish as their fisheries have declined.

The stings and emergency shutdowns are bad – and let’s face it, that whole slimy thing is a bit off-putting – but the real problem with jellyfish is in their predator-prey dynamic with fish. On the face of it, fish are obviously the superior predator: They are smarter, faster and often bigger. Think of sharks and stingrays and largemouth bass: It’s hard to imagine that jellyfish could possibly hold their own against these fighters. But jellyfish are sneaky. They eat the eggs and larvae of fish, and the plankton that the larvae would eat. And through this double whammy of predation and competition, they can cripple an ecosystem at the ankles.

But jellyfish do other harm, which is only just beginning to be appreciated. They flip the food chain upside down. Normally as you go up the food chain, the energy value increases. For example, shrimp pack more energy than their plankton prey, but big fish that eat shrimp are better still. Hower, jellyfish, a very low-energy choice compared with shrimp or fish, are sequestering the higher energy of these species into their own low-energy bodies. They are, in essence, spinning gold into straw, or turning wine into water.

In a healthy ecosystem, fish are superior competitors and predators over jellyfish. But the things we humans do – we fish, we pollute, we dam, we build, we translocate – are making life harder for fish and better for jellyfish. And so, as we look around the world, we see that many of the most heavily disturbed ecosystems have “flipped” to being dominated by jellyfish instead of fish. Moon jellies and comb jellies in the Inland Sea of Japan. Sea nettles in the Chesapeake and the Benguela current off Namibia. Comb jellies in the seas of Europe. Santa’s hat jellies in the fjords of Norway. Refrigerator-sized jellies growing in the seas of China and drifting into Japanese and Korean waters.

And once in control, they don’t seem to be letting go.

So, we find ourselves in the unimaginable position of being in competition with jellyfish – and make no mistake, they have the home-court advantage.

So, what can we do? What should we do? That’s the problem. The ocean is our life support system – it’s where we get our food, our oxygen, many of our industries and often our inspiration. But we don’t have a solution for the damages we are causing. We need to buy time, so solutions can be innovated.

We need to invest in research to slow down the damage as well as to cope with our rapidly changing world. And we need to begin serious dialogue about what we value and what we are willing to do to preserve it.

We could start by legislating a clean-to-intake standard in which any air or water discharged by industry must be at least as clean as it was going in, or the industry is not permitted to operate. Sure, there would be great gnashing of teeth, but quite quickly, polluting industries would have to innovate ways to be cleaner to stay economically viable. This is just one example, but we must think of many more. And we must do something.

I read somewhere recently that we in all likelihood will go down in history as the generation that could have saved the ocean but chose not to. It made me cry, because I fear it is true.

Follow us @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Lisa-ann Gershwin.