Read a version of this story in Arabic.

Story highlights

Social media sites are wrestling with how to police hateful speech

A man in England was arrested after a feminist received rape threats on Twitter

Sites have difficulty policing millions of users

But expectations are high as Twitter, Facebook have become more mainstream

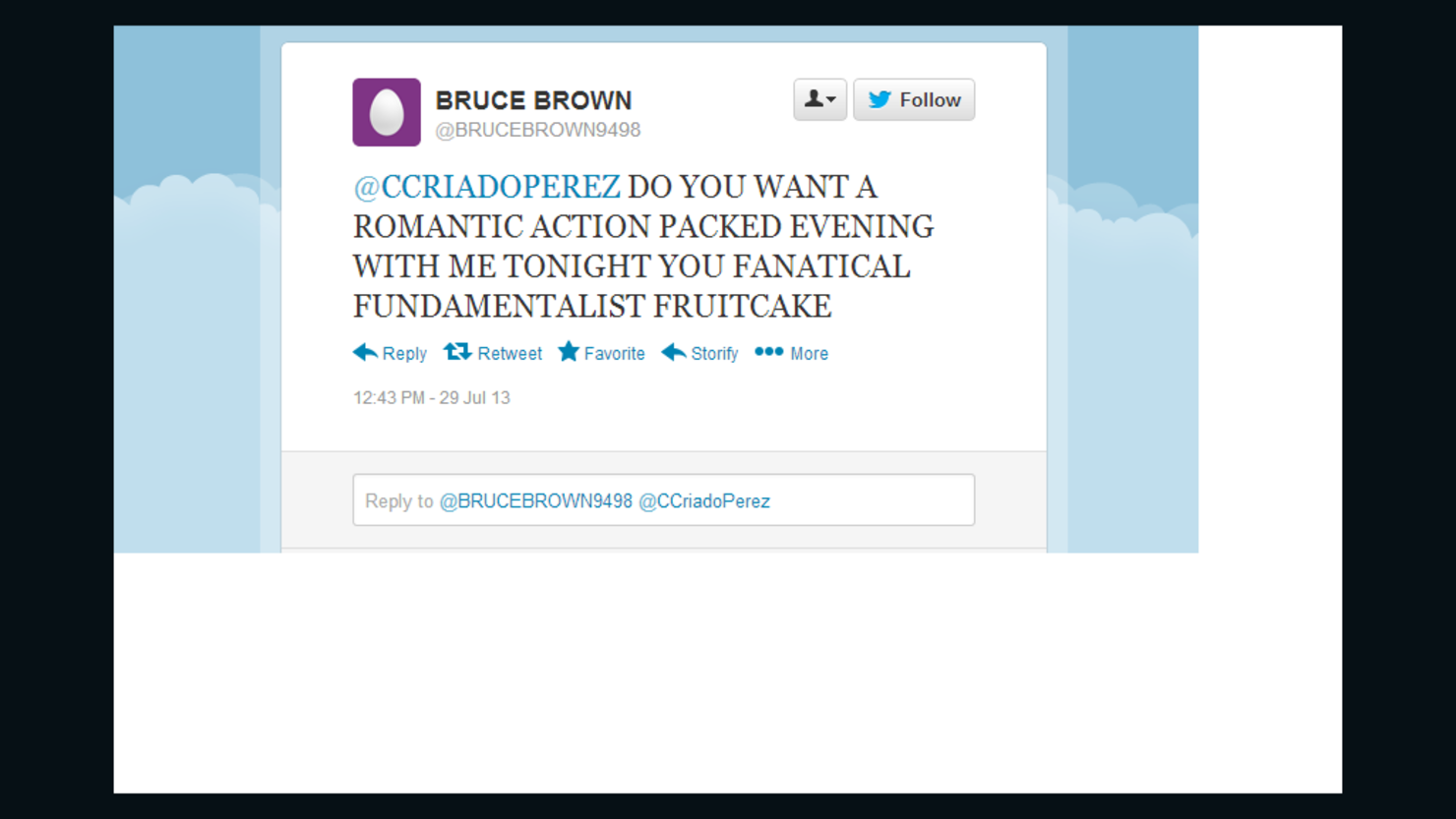

An advocate for honoring women on British currency was thanked for her efforts on Twitter with dozens of rape threats. A female writer who recently spoke out against rape jokes, almost predictably, got the same treatment.

Meanwhile, Facebook was called to task for not being quick enough to stamp out pages such as “Fly Kicking Sluts in the Uterus” and “Violently Raping Your Friend Just For Laughs.”

Hateful words and actions targeting women and other groups are, of course, nothing new. But in our digital age, social media sites must increasingly face the fact that their services have become the new schoolyard or city square, where a majority of friendly discussion and positive interaction comes with an ugly undercurrent of nastiness.

“Expressed hate and abuse is unfortunately part of our society, and it is now also part of our real-time digital culture,” said Brian Solis, a new media analyst for Altimeter Group and author of “What’s the Future of Business? Changing the Way Businesses Create Experiences.”

“As we live the digital lifestyle, our expectations are such that any menace should not only be dealt with accordingly, it should be done immediately.”

The question for sites such as Twitter, which on Tuesday responded to a petition to make reporting abusive behavior easier, is how to police hundreds of millions of people, providing a safe environment for some users while respecting the free speech of others.

At the heart of the problem are the mechanics of policing. The sheer number of users means that flagging misbehavior is like playing a vast, never-ending game of Whac-a-Mole.

“Twitter represents a new medium that the world hasn’t seen before,” Solis said of the site that supports 400 million tweets every day. “To protect its users, it must invest in automated and manual safety and reporting mechanisms as it grows.”

This week, the Bank of England announced that “Pride and Prejudice” author Jane Austen will be featured on 10-pound notes. The move came after a campaign by Caroline Criado-Perez and others.

On Twitter, Criado-Perez wrote that the response got ugly fast: “I actually can’t keep up with the screen-capping & reporting – rape threats thick and fast now,” she wrote now. “If anyone wants to report the tweets to Twitter.” Some of the accounts she cited have since been suspended.

Eventually, one man was arrested Sunday in Manchester, England.

British police also are investigating a threat of rape and murder made to Stella Creasy, a Labour Party member of Parliament, after she tweeted her support of Criado-Perez.

But activists complained that Twitter didn’t act quickly enough. A Change.org petition, calling on the site to add a prominent “report abuse” button, had gotten more than 88,000 signatures as of Tuesday.

The effort prompted Del Harvey, Twitter’s senior director for Trust & Safety, to respond Tuesday in a blog post titled “We Hear You.”

“We see an incredible amount of activity passing through our systems …,” she wrote on Twitter’s UK blog. “The vast majority of these use cases are positive. That said, we are not blind to the reality that there will always be people using Twitter in ways that are abusive and may harm others.”

Harvey noted that three weeks ago the site rolled out a tool for Twitter for iPhone that lets users report individual tweets. That feature will hit Web and other mobile systems soon, she wrote.

She acknowledged, however, that putting eyeballs on every offensive tweet is difficult, if not impossible.

“While manually reviewing every tweet is not possible due to Twitter’s global reach and level of activity, we use both automated and manual systems to evaluate reports of users potentially violating our Twitter Rules,’ Harvey wrote. “These rules explicitly bar direct, specific threats of violence against others and use of our service for unlawful purposes, for which users may be suspended when reported.”

The movement, and response, are not unlike a similar recent effort on Facebook.

In May, a coalition of women’s groups called for the site to get tough on pages that appeared to embrace hate speech, particularly violent language, toward women.

Facebook responded by rolling out a slate of efforts that, among other things, increased accountability for pages that post content that is “cruel or insensitive.”

Speaking Saturday at the BlogHer conference in Chicago, Facebook Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg acknowledged the difficulties in policing abusive behavior among the site’s more than 1 billion account holders. But she said tools to do so continue to improve.

“We have this really big challenge between free expression, which is really important …, and creating a safe and protected community,” she said. “We take both very seriously.

“The No. 1 thing people can do is when you find content that’s inappropriate, there’s a report button. Hit that report button because we can look at and take down inappropriate content as long as we see it, and (it) is really an important part of what we’re trying to do.”

Both the Twitter and Facebook episodes mark what appears to be a shift in online culture. Throughout the Web’s history, a certain amount of bad behavior has come to be expected, be it intentionally provocative online trolling or earnest hatred spewed more freely because of the ability to do so anonymously.

But, in 2013, it’s become nearly impossible to distinguish where “Web culture” ends and culture as a whole begins. Solis, the analyst, noted that as social media become more and more mainstream, bad behavior that would never be accepted on a sidewalk will increasingly be policed, one way or another, online.

“The idea of ‘freedom of tweet’ does not supersede law,” he said. “Expression aimed at hurting or threatening someone is indeed a threat heard around the world.”