Story highlights

Marco McMillian returned to his hometown in the Mississippi Delta to run for mayor

Before his campaign took off, he was killed, and rumors spread quickly

Some called it a hate crime because McMillian was a black man and openly gay

His family and friends believe McMillian found out unsavory things about Clarksdale

Beaten. Dragged. Burned.

The words leave attorney Daryl Parks’ lips like a barrage of gunfire in the sanctuary of Chapel Hill Missionary Baptist Church, where people have gathered not for prayer but for answers.

Some wear “Justice for Marco” T-shirts. They are enraged over the investigation into the death of Marco McMillian, a young black gay mayoral candidate, whose broken body was discovered dumped downhill from a Mississippi River levee on February 26.

Parks’ words suggest the most heinous of murders. Here in the Mississippi Delta, they conjure even more: a chilling history of racial hatred.

“Don’t stop; don’t give up,” Parks says. “Somebody will explain the burn marks on his body. Somebody has to explain the torture he went through.”

“Yes, yes,” responds the crowd gathered on this June day for an NAACP-sponsored town hall meeting on McMillian’s death.

It has been four months, Parks says. Four months, and the sheriff has not come to see McMillian’s family. Four months, and he has not responded to a letter from McMillian’s mother.

Lawrence Reed, the key suspect, who is also black, is behind bars at the Coahoma County jail, awaiting a preliminary hearing early next month. The sheriff’s department says it has the right man in custody.

Beyond that, Sheriff Charles Jones has said little, and the dearth of information stokes suspicion in every corner of this city soundly divided by race and class. Rumors about McMillian’s death spread faster than the Mississippi’s water swells in the Delta.

McMillian’s mother, Patricia Unger, has heard them all.

Some impugn her son’s reputation. Some point to corruption and suggest he died because he knew too much. Unger and other family members are convinced there is more to McMillian’s killing than the one man being blamed for it. And she lacks confidence that local authorities will solve the mystery surrounding the death of her only child.

“Marco was brutally murdered. That much we know,” said Carter Womack, McMillian’s godfather and spokesman for the family. Unger is hearing-impaired and does not feel comfortable speaking in public.

“We have to raise the level of voices,” Womack said. “Otherwise, it’s just another black man dead in Mississippi.”

An angel in a town possessed by the devil

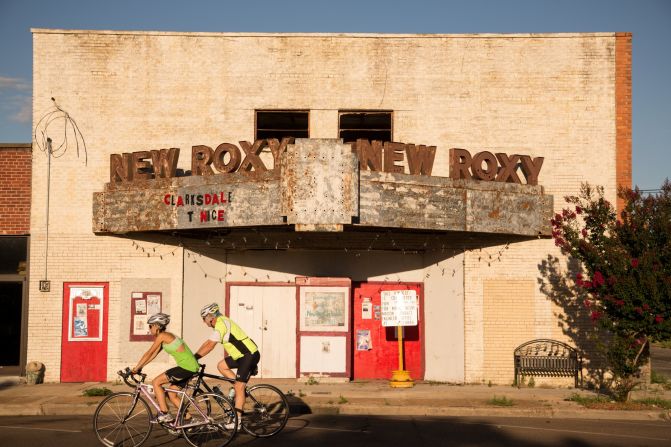

It was not long ago that McMillian returned to his hometown of Clarksdale and announced he was running for mayor.

On paper, his platform was straightforward: reduce crime, improve educational opportunities and spur economic growth.

That would have to be every politician’s agenda in this bleak Delta city where the population of 18,000 is shrinking by the day. About 40% live below the poverty line, though that number doesn’t even begin to convey the despair that hangs as heavy as the damp air.

Many of Clarksdale’s residents, weary of stagnation in their lives, believed McMillian was the right man for the job. He was one of their own, an angel who’d come back to a town possessed by the devil. It was in Clarksdale, after all, at the crossroads of Highways 61 and 49, that music legend says blues man Robert Johnson sold his soul in exchange for unmatched guitar skills.

But before McMillian’s campaign even took off, he was dead.

He had been missing for many hours when deputies discovered his body by a levee 20 miles west of town. They were tipped off by Reed, who was found alone in the wreckage of McMillian’s SUV on the morning of February 26. Critically injured and taken to a Memphis hospital for treatment, Reed reportedly confessed to police that he had killed McMillian and told them where to find his body.

Some here believe McMillian was killed because he discovered too much about his hometown. He was a black man who challenged the largely white establishment. “I want to know why this isn’t being called an assassination,” said Darrell Gillespie, a former classmate of McMillian’s.

Parks, who stepped forward to represent McMillian’s family and whose law firm represents Trayvon Martin’s parents in Florida, fuels those theories. He says McMillian discovered information that had “some components of public corruption. It’s very serious.”

So serious that Parks says he is concerned about the family’s welfare.

Others believe McMillian and Reed were sexually involved, that the killing was domestic violence. Or, they say, Reed killed McMillian in a fit of rage after the latter made sexual advances. Reed is not gay, his friends said.

Initial media reports implied that perhaps McMillian, described as Mississippi’s first viable openly gay candidate, was killed because of his homosexuality in a state that has no hate crime laws to protect LGBT people. The story was made out to be a modern-day civil rights case.

New York slaying considered hate crime

One media report even drew a parallel between McMillian’s killing and that of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old boy who was abducted, beaten and shot in 1955 after allegedly flirting with a white woman. His body was found in a river just a few miles south of Clarksdale and galvanized a then-fledgling civil rights movement.

But to call McMillian a trailblazer as an openly gay candidate might be far-fetched. Many in the community did not know his sexual orientation; he hadn’t made it an issue in the mayoral campaign, nor had any of his opponents.

The sheriff’s department charged Reed with McMillian’s murder. Spokesman Will Rooker said there was no evidence to support allegations that it was a hate crime. Reed has not entered a plea.

Still others in Clarksdale questioned why McMillian’s death was even newsworthy. It was just another homicide in a town rife with violence. There were about 40 gun-related crimes just in April and May, the local newspaper reported. Drive-by shootings – even the killing of a 68-year-old grandmother – don’t shock residents anymore.

‘They are coming after me’

Unger was in labor for nine hours before Marco was born at 2:11 p.m. April 23, 1979. He was an energetic baby with strong lungs.

When her son was 6, Unger and her husband divorced, and she raised Marco by herself. He was a good kid who threw tantrums when he didn’t get his way. “In other words,” she said, “he was spoiled.”

People told her she was overprotective. She didn’t care and catered to her son’s every need. She served him breakfast in bed even after he was grown up.

He was furiously curious about the world and loved to learn new things. He liked to skate and bowl with his friends and sang in the church choir. He also spent a chunk of his time around older people and emerged as a leader among his schoolmates. They remember a kid who helped mediate quarrels and stop fights.

“He was the peacemaker,” said LaSonya Wilson, 34, who knew McMillian from childhood.

He led the effort to integrate his high school’s prom in 1997 and to find the money for the first senior trip (to New York and Washington) since the school was desegregated in the 1970s.

Later, people noticed when he began to talk about bringing change to a town where a lot of black kids just wanted to escape.

“Marco dreamed about putting Clarksdale on the map,” Wilson said.

McMillian followed his dreams and made a career for himself, graduating from Jackson State University and then earning a master’s degree in development and philanthropy from Saint Mary’s University in Minnesota. His résumé was impressive.

He’d served as the international executive director of the historically black Phi Beta Sigma fraternity and as an administrator at Jackson State and Alabama A&M. He moved to Memphis to work as a recruiter for New Leaders, an organization that trains school principals.

In 2009, he received the Thurgood Marshall Prestige Award, and in 2004, Ebony magazine recognized him as one of the nation’s top leaders under 30. He proudly showed off a photo of himself with a young Barack Obama.

But McMillian was not without blemish.

He was part of a payroll scandal that ousted Alabama A&M President Robert Jennings, who was found to have hired McMillian in an executive assistant job though he was not qualified and not even present for a few weeks while he was finishing his master’s.

McMillian also started his own consulting firm for nonprofit organizations, though its website provided little information. When a reporter from the Clarksdale Press Register covering the mayoral race inquired about McMillian’s business, McMillian cut him off, saying he was not required to answer those questions.

Some people who knew McMillian described him as the kind of person who got what he wanted and could come off as pushy and arrogant.

“He never took ‘no’ for an answer,” said Brad Fair, another Clarksdale mayoral candidate who’d known McMillian since their school days.

Fair remembers the day McMillian told him he intended to run for mayor after the incumbent, Henry Espy, decided four terms was enough. Fair was upset. McMillian had promised to support him. Now he was saying he would be his primary opponent.

“He was definitely CEO-minded,” Fair said. “He knew how to maneuver to get things he wanted. He knew how to work his way up to the top. He was so confident he was going to win (the mayoral race) – to the point where I began to think, ‘Why am I even running?’ “

In the end, Fair ran as an independent so as to not compete for votes against McMillian in the Democratic primary but lost in the general election.

McMillian thought Fair needed more experience. Besides, he told Fair, he was on a mission from God.

McMillian’s mother could not understand why he chose to return to Clarksdale. She asked, “Why?”

Why would you want to give up a good salary, your standing in life, and move back to this place? she asked. His friends wondered the same thing.

McMillian told them he felt compelled to do something to help improve the quality of life in his hometown.

“Moving Clarksdale Forward.” That’s what he chose as his campaign slogan. An official photo showed him standing in front of a cotton field.

His friends knew he was ambitious. He dreamed of running for Congress one day.

Fair believes McMillian may have discovered unsavory information about local politicians, whom some accuse of corruption and dysfunction in Clarksdale.

“Marco was too smart for his own good,” Fair said. “I am confident Marco knew the facts.”

Fair could not name any specifics but offered his city’s despair as evidence.

“Look at our city. Look at how it’s dying. Do we have corruption? Most definitely.”

What, if anything, McMillian knew might not be known until a trial, but some Clarksdale residents said they have been steadily losing trust in local government. Allegations of scandal that tainted Espy, the previous mayor, did not help.

Espy, who first became mayor in 1989, was indicted – and later acquitted – on charges of conspiracy and making false statements in connection with a $75,000 bank loan to repay debts incurred in a campaign to win a congressional seat vacated by his brother Mike Espy. And Mike Espy resigned his post as agriculture secretary in the Clinton administration because of an investigation into gifts and favors from agribusiness firms. He, too, was later acquitted.

Henry Espy’s son, state Rep. Chuck Espy, was one of several candidates who ran against McMillian for mayor. Neither Espy responded to requests for an interview.

McMillian’s supporters have harsh words about Clarksdale’s politicians, be they white or black.

“Local government has failed us for the past 20 years,” said Angela Maddox, another childhood friend who worked on McMillian’s campaign. “I think there are powerful people who are in hiding.

“This story is not just about Marco,” she said, “but what Marco was about to uncover in Clarksdale.”

Matt Killebrew, publisher of the Clarksdale Press Register, said he was not aware of any wrongdoing at City Hall.

“I think Marco was a bit defensive,” he said, “as any black candidate would be in the Mississippi Delta.”

Asked about allegations against local government, which are not hard to come by in Clarksdale, the man who just took office as mayor said he would look into them.

“In terms of widespread corruption, I don’t know that any exists,” Bill Luckett said, “but I will investigate. Sometimes, the husband’s the last one to know the wife is having an affair.

“I’ve heard some rumors: that I had (McMillian) killed, (that) Chuck Espy had him killed. I just had to let my skin get thick and not even pay attention to things like that.”

But McMillian’s supporters believe people who wield power in Clarksdale wanted McMillian to go away.

In an interview with CNN, Maddox pulled out her cell phone and displayed text messages she said she received from McMillian just a few days before his death. CNN could not independently verify that the number on Maddox’s phone, which showed up as “Marco cell,” belonged to McMillian.

When asked about the number, Parks, the family attorney, said McMillian’s “cell phone is part of the criminal investigation.”

The texts suggest trouble.

“Help me my dear love. Cause they are coming after me,” he wrote on February 6.

“Who is coming after u?” responded Maddox.

“The White establishment,” he said.

“What’s being said? Maddox asked.

“Trying to buy me out of the race.”

Maddox said she told an investigator with the Coahoma County Sheriff’s Department about the texts she received, but she said no one has asked to see her phone messages.

McMillian’s mother says her son had also warned her that something bad might happen to him. This is what she recalls he said:

“If you get a call and they tell you I am missing, or that my body was found in the woods somewhere, do not be surprised. These people are out to get me out of the race. I am uncovering stuff they do not want people to know about.”

A fatal meeting

About 10 p.m. February 25, McMillian told his mother, a special education teacher, and stepfather, Amos Unger, a custodian, that he was stepping outside to move the cars in the driveway.

He was supposed to be driving the 70-plus miles north to Memphis in the morning. He had moved back to Clarksdale last fall and settled back into his childhood home on Lyon Avenue before announcing that he was running for mayor in January. But he commuted often to Tennessee for his job at New Leaders.

About the same time, in another house just a few blocks away on Grant Place, Lawrence Reed also went out the front door, recalled his friend Kamilla Crump.

Reed graduated from Broad Street High School in the nearby town of Shelby but moved to Clarksdale afterward. Crump met Reed through her husband, Deric, about four years ago. He worked at the Domino’s Pizza around the corner on DeSoto Avenue. One night last year, when it was raining hard, the Crumps let Reed crash in their house. After that, they agreed Reed could live with them if he helped pay the bills.

Kamilla Crump started calling Reed her older brother. “He is one of the best men I know,” she said. The kind of person who was there for her and her family when they were in need. He’d watched her little girl grow up; he was practically family.

She described Reed using the same terms McMillian’s friends used to describe the slain man: hard-working and a real go-getter.

When Reed left the house, Crump thought nothing of it. It was late, but he’d been home all day. Maybe he needed to go out and get some air.

At McMillian’s house, Amos Unger got out of bed about midnight and noticed his stepson was not at home. He thought it was odd; Marco always told his momma where he was going.

It’s not clear whether McMillian and Reed knew each other before that night. A friend of Reed’s said the two were acquainted. McMillian’s friends and family say, “no.”

What happened between 10 p.m. February 25 and the arrest of Reed the next morning may not be known until a trial begins – or ever. But a friend of Reed’s says she saw him just before his arrest. She spoke with CNN on the condition that she remain anonymous because she fears harassment. She offered these details.

The friend said Reed showed up at her house on Highway 49 the morning of February 26. He was bruised and bloodied, she said, and driving McMillian’s 2005 black Chevy Tahoe.

According to the friend, Reed and McMillian planned to go to a party in the nearby town of Marks. Reed told his friend that McMillian had whiskey and marijuana on him. At some point, she said, McMillian drove Reed down a dark road and made sexual advances.

“Marco wanted to have sex. He started taking his clothes off. Lawrence is not gay,” the friend said.

A friend of McMillian’s, LaSonya Wilson, also knew Reed. She’d met him at the Kroger gas station where she worked and when he delivered pizzas at her house. She described Reed as a nice guy.

“I know this boy. He wasn’t even Marco’s type,” she said, meaning McMillian associated with older, more established men, not a 22-year-old, a baby.

McMillian’s friends all knew he was gay, from the time he was a boy. “He always acted feminine. He was flamboyant,” Wilson said.

But McMillian grew up in conservative Mississippi, in an insulated African-American community. Being gay was taboo.

McMillian’s mother said she was not certain of her son’s sexual orientation.

“If I had actually known that he was gay, it would not have changed my love of feelings for him,” she said.

Reed’s friend said Reed panicked when McMillian came on to him.

“I think the boy just snapped and went cuckoo.”

The National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs issued a statement saying it had learned that Reed might use “gay panic” as his defense if and when he is tried. It’s the same tactic that was used to defend the killers of Matthew Shepard, the University of Wyoming student who was tortured and killed near Laramie in 1998.

The so-called gay-panic defense argues that a defendant’s assault against an LGBT person should be excused or classified as a lesser charge because the revelation of a victim’s sexual orientation caused the perpetrator to lose control and turn violent.

In an effort to protect gay victims of heinous crimes, the American Bar Association is considering a resolution that urges governments to curtail the use of that defense.

But that is how Reed’s friend views what happened. When he showed up at her house, he told her he wanted to kill himself; he was already “going to hell” for having engaged in immoral acts.

Then, he turned left out of her driveway, back onto Highway 49. She called 911 and told police what Reed had told her.

CNN requested a copy of the transcript of the 911 call as well as Reed’s arrest report and other documents pertaining to this case. The request is still pending. The sheriff did not respond to an interview request.

Reed was driving south, toward the Tallahatchie County line, when he hit an oncoming car head-on. Deputies responded to the accident about 8:30 a.m.

The driver of the other car, Chris Talley, was taken to a local hospital where deputies gave him shocking information, he told WMC-TV in Memphis: He learned there that Reed told a deputy that he had killed someone the night before and dumped the body. The alleged confession would also later be cited in an autopsy report.

All that day, there was no word of McMillian. His mother texted people furiously, desperate to know her son’s whereabouts. Deep inside, she feared the worst.

Memories of Emmett Till

The next morning, Scotty Meredith got a call from the chief sheriff’s deputy in Coahoma County. Authorities had found a body and were waiting for Meredith, the county coroner, to come examine it before it was moved.

Meredith had received countless such calls. He’s no stranger to death.

His first encounter came when he was only 12. His daddy died of lung cancer. He was curious about what was done to his father’s body, and by the time he was 15, he’d started working in the funeral business. Now he’s 50, and a downtown funeral home bears his name.

Clarksdale’s high homicide rate keeps him busy. He’s had to walk many a mother to the morgue. They tell him: “You know, Mr. Meredith, I don’t have to worry about where my son’s at anymore.”

Clarksdale is one of those towns where a lot of people know one another, but Meredith had never encountered McMillian. The first time he saw him was down from the earthen levee that ran between the unincorporated communities of Rena Lara and Sherard.

Meredith parked his car and walked down the hilly pasture where fresh tire tracks had led deputies to a barbed-wire fence that keeps grazing horses and cows inside the levee board property line. Beyond it are thick trees and then the river.

McMillian’s body had been dragged under the fence.

Meredith saw a naked man with a burn the size of a half-dollar on his left hand. He had a few blisters, cuts and bruises here and there, and his right eye was swollen.

Meredith bagged McMillian’s hands and feet to protect them in case they turned up evidence and put him in a body bag. He took out his cell phone and clicked a picture before sending the body away to Jackson for a state medical examiner to conduct an autopsy.

Then, Meredith went to see Unger at her home.

“I told the sheriff that his mom needs to know about her son – doesn’t matter whether he’s 3 or 33.”

He took out his phone and showed Unger the photo.

“That is my son,” she told him.

He did not believe that McMillian was beaten to death but thought he had been dragged from the car, maybe 20, 30, 40 yards. He told Unger it looked like it may have been difficult for one person to have done that.

Unger felt frustrated. The sheriff had not come to the house. No one wanted to see McMillian’s things, his laptop. Wasn’t that a part of any murder investigation? Nor had anyone from the victim assistance office contacted her.

Three days after the body was recovered, McMillian’s family released a statement based on their interpretation of what Meredith had told them. They believed McMillian had been tortured before he was killed.

They also believed Reed had not acted alone. McMillian weighed 220 pounds. Reed is a small guy. There was no way, they thought, that Reed could have done this by himself.

“We feel this was not a random act of violence based on the condition of the body when it was found,” they said. “Marco, nor anyone, should have their lives end in this manner.”

By the time McMillian’s funeral was held March 9, many news reports had cast the murder as a hate crime. The family suspected it was a conspiracy of sorts. An autopsy was performed the day after he was found, but it would take six weeks for its release.

The National Black Justice Coalition, whose aim is to empower black LGBT people, said McMillian’s death and the “ongoing investigation highlighted the complexity of life for openly gay black men in Mississippi.”

McMillian’s body lay in a blue casket, his face and body disfigured. The Memphis Commercial Appeal newspaper said he resembled Emmett Till.

The service was tearful. Unger felt faint after seeing her son’s body and had to be helped to her seat. Civil rights activist and Georgia Rep. John Lewis told the crowd that Marco would live on through the good he had done his community.

As days turned to weeks with no word from authorities, Unger’s frustration turned to anger.

Blacks die earlier from homicide, heart disease

Autopsy raises more questions

Finally, on May 1, Mississippi Chief Medical Examiner Mark LeVaughn signed and released McMillian’s autopsy report.

The conclusion: He had died of asphyxiation. Multiple areas of blunt trauma to the head that are consistent with a beating most likely contributed to his death. It could not be determined whether he was burned before or after his death, but a chart showed burns on McMillian’s calves, back, right arm and left hand. The abrasions on his knee were consistent with a “drag type” injury.

The report listed details about blood vessels bursting in McMillian’s right eye and said he had bit his tongue. Everything suggested that McMillian had met with a grisly end.

But the autopsy raised more questions. How did he choke to death? There were no marks around his neck.

Meredith, the coroner, refused to sign the autopsy, the first time he’d done that in 24 years on the job.

He disagreed with its findings: What the medical examiner said didn’t match what he had seen that day at the levee. He thought the autopsy made McMillian’s injuries far more serious than what he observed.

“I am not comfortable putting my name on it,” he said. “It’s my reputation.”

He said the family wants to believe it was a hate crime, that he was targeted because of race or sexual orientation. But in Meredith’s mind, it wasn’t.

“If it were my child, I’d want it to be on the national news. But it is what it is.”

The friend whom Reed visited after McMillian was killed also believes it was meeting between two men that went terribly wrong. She said Reed was trying to defend himself against rape, that there were two victims that night.

“Everything is not based on race,” said the friend, who – like Reed – is black. “I feel for his family, but we don’t know what happened that night. None of us were there.”

Shortly after the autopsy was released, McMillian’s family held a news conference and demanded a federal investigation. Unger wrote a letter to Eric Holder, the attorney general of the United States, asking him to look into the killing of her son.

“When you hear that a man has been beaten, dragged and burned, what’s the first thing that comes to your mind, regardless of the fact that we are living in the 21st century?” Unger wrote. “Even though most newspapers are reporting the murder as an ‘openly gay mayoral candidate found dead,’ further investigation is needed.”

In her letter, Unger described her son’s warnings that people were out to get him. The Justice Department has encouraged others in the community to send in their concerns.

McMillian’s death made national headlines. The media descended on Clarksdale to write about the murder of a gay black man in a backward Delta town, coverage that rankled some residents.

“I think we’re getting a black eye because we’re the Mississippi Delta,” Meredith said.

Through it all, the mayoral race continued with a runoff and an election on June 4. Luckett, the winner, agreed that his city was getting a bad rap.

“The thinking is if you’re black and you’re gay and you’re running for mayor, then some redneck is going to get you,” he said, sitting inside the restaurant and music venue that he co-owns with actor Morgan Freeman, the Ground Zero Blues Club.

“He wasn’t killed because he was black. He wasn’t killed because he was gay. It’s just a tragic but bizarre set of facts,” he said.

Luckett, a millionaire lawyer and businessman, was born and raised in Clarksdale. He speaks with Southern swagger and draws an unmistakable silhouette with his thick, combed-back hair and portly frame. He takes great pride in showing off Ground Zero and the apartments for rent above it and believes that investments like that can help turn Clarksdale around from decay to renewal.

Luckett made a run for governor of Mississippi – as a Democrat – and lost. McMillian’s supporters said Luckett eyed the mayor’s job so he could try again for governor with a feather in his cap – to be able to say that he was the one who turned things around in his hometown.

McMillian, said his supporters, had momentum and had a real good chance of winning. Without him in the race, Luckett’s victory was a landslide.

‘Mississippi Goddam’

Several speakers take the microphone at the town hall meeting inside Chapel Hill Missionary Baptist Church. They cry injustice and foul play and direct their venom at Charles Jones, the Coahoma County sheriff.

“The sheriff not responding is about as offensive as you can be,” says Parks, the McMillian family attorney who has left George Zimmerman’s trial in Florida to be in Clarksdale on this day.

The sheriff’s name is the final one on the schedule of events. But he is not here.

People look around the sanctuary. Sitting in the back is the only white person in the room, besides members of the media. It’s Will Rooker, the sheriff’s spokesman. He makes his way to the podium; all eyes follow him with the precision of an animal stalking its prey.

Rooker looks nervous. He reads from a prepared statement. He says again that authorities have the right man in custody, that there is no evidence to indicate that this is a hate crime.

“The Coahoma County Sheriff’s Department is committed to building a case that’s completely based on facts,” Rooker says. “We can’t allow ourselves to be influenced by gossip on social media.”

The disappointment is palpable, especially for Unger. She has not learned anything more about why or how her son was killed.

She asks everyone to write to a Department of Justice representative who has come to Clarksdale for this meeting. She is convinced outside help is needed to solve Marco McMillian’s murder.

Toward the back of the church, one woman nods her head in agreement. Then, she whispers the title of singer Nina Simone’s civil rights anthem. “Mississippi Goddam.”