Editor’s Note: Arianne Chernock is an associate professor of modern British history at Boston University. She’s at work on a book titled “The Right to Reign and the Rights of Women in Victorian Britain.”

Story highlights

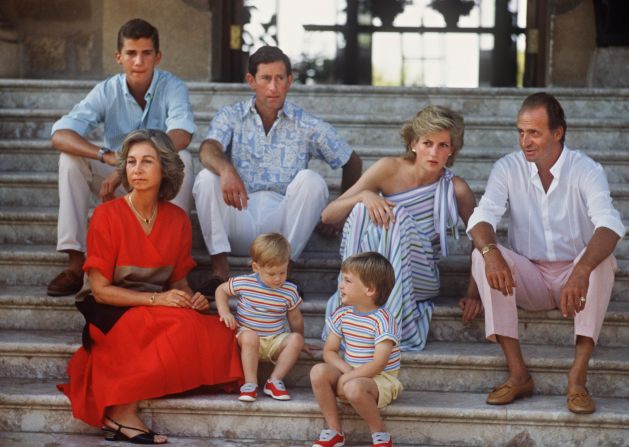

Arianne Chernock: Popular opinion prefers that Prince William and Kate have a girl

Chernock: The fervor has to do with a new succession law that gives girls equal rights

She says another reason is women have worn the crown in Britain in recent history

“I hope you have a boy.” These were the words of a well-wisher to Queen Elizabeth II (then Princess Elizabeth) and Prince Philip on the eve of the birth of their first child in 1948.

Prospects look considerably brighter for royal girls in 2013. Over the past few weeks, as the craze surrounding the birth of the Duke and Duchess’s first-born has reached fever pitch, there’s been very little fantasizing of princes per se. If anything, the pendulum now seems to have swung the other way.

Perusing the web, I’ve been struck by how many comments indicate a popular preference for a girl. To quote one particularly enthusiastic respondent to a recent article on the royal birth, “I’m personally wishing it to be a girl for the good of the entire human race and the sustainability of the planet.”

Why the shift in sentiment?

In part, the enthusiasm for royal daughters can be attributed to the passage of the Succession to the Crown Act, which became law in late April 2013. The act, greenlighted to save the British government from the embarrassment of denying the throne to William and Kate’s first-born – should that first-born be a girl – erases the male preference in royal succession.

The change in law means that the new royal baby, regardless of its sex, will be third in line to the throne. Thus, the refreshing banality of Kate’s recent statement that, “I’d like to have a boy – and William would like a girl!” From a constitutional perspective, the sex of the child no longer makes a difference.

There’s another reason for the eagerness, at least in some quarters, for a female heir. The very uncontroversial nature of the passage of the Succession to the Crown Act reflects a particular historical reality in Britain. Male preference aside, women have worn the crown there for most of the past two centuries.

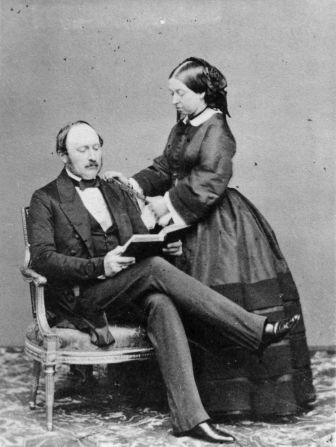

Queen Victoria reigned for almost 64 years; Queen Elizabeth II has already clocked in 61. That’s a lot of time to get accustomed to female sovereigns. And not just accustomed to them, but extremely fond of them in the process.

While Victoria’s reign (1837-1901) was regarded as an “accident” until the very end, it was an “accident” that most Britons came to consider a very happy one. As the muckraking journalist William Thomas Stead proclaimed in 1897, the year of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, “England indeed has been fortunate in her Queens.” So confident was Stead in queens’ abilities to lead the British nation that he would go on to note that, “Many a time and oft has the idea recurred in these later years whether by some inversion of the Salic law our dynastic line could be made to pass only through female sovereigns. This being past praying for, we shall do well to make the most of our good Queens when we have them.”

Surely there was something overly compensatory about Stead’s remarks. Queen’s reigns, under the terms of the old succession laws, were always understood to some extent as aberrational. As Victoria herself once confided to her prime minister, William Gladstone, “The queen is a woman herself and knows what an anomaly her own position is.”

Yet the “anomalousness” of female sovereigns was far more of a problem in the early modern period than in the modern time. After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Britain emerged as a constitutional monarchy, with the king – or queen – taking on an increasingly ceremonial or “dignified” function. Women have shone in this role (both on and off the throne), helping to transform the monarchy into an institution intimately connected with cultural diplomacy, middle-class morality, family life and charity work. (Queen Elizabeth is currently involved with more than 600 different charities.)

Historians often describe this as a “feminization” process. Whatever it is, it’s a role to which women, for a wide range of reasons, are more habituated to playing.

The real question we should be asking, then, in the days leading up to the royal birth, is not ‘boy or girl?’ It’s whether we would have the same levels of enthusiasm, or at least complacency, regarding a female heir, if that heir were to inherit a position that had significant executive, legislative or judicial powers.

Follow us @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions in this commentary are solely those of Arianne Chernock.