Editor’s Note: Meg Urry is the Israel Munson professor of physics and astronomy and chairwoman of the department of physics at Yale University, where she is the director of the Yale Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Story highlights

NASA says planet-finding Kepler satellite directional equipment failing

Meg Urry says Kepler has found 2,700-plus exoplanets, some that may harbor life

She says NASA's resourceful scientists working to fix it; loss of its photometry would be huge

Urry: Yale prof has other method to find exoplanets; we're bound to eventually find signs of life

On Wednesday, NASA officials announced a serious problem with the Kepler satellite, the world’s most successful planet-finding machine.

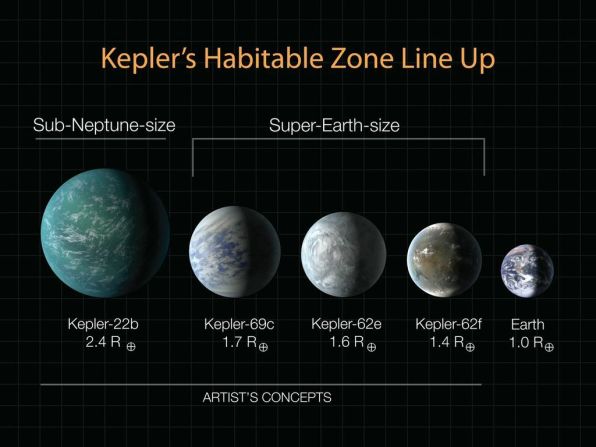

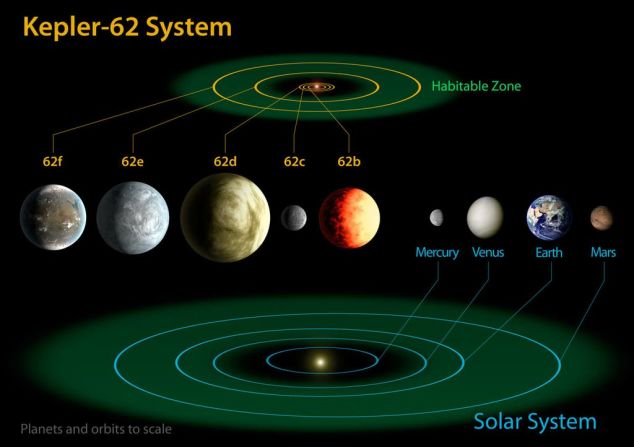

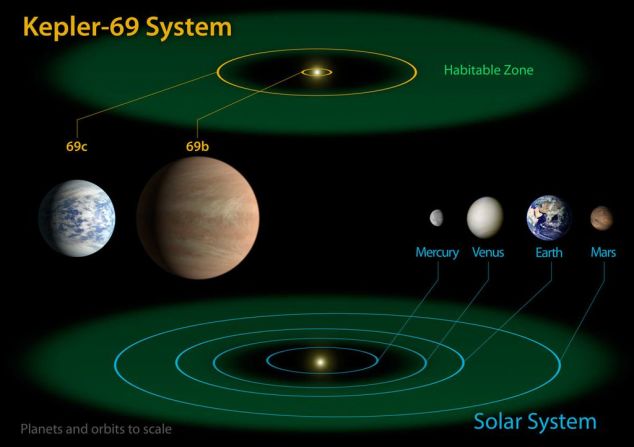

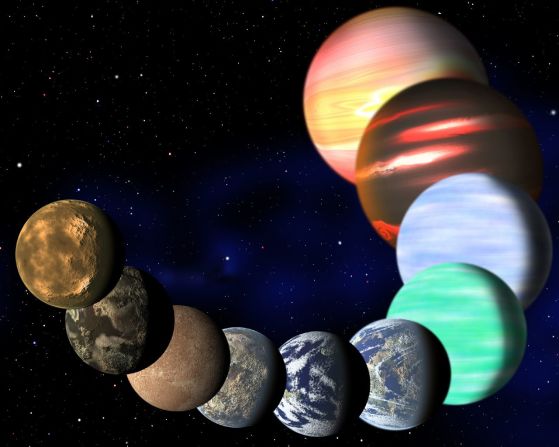

Since its launch four years ago, Kepler has found more than 2,700 possible planets orbiting stars other than our Sun, of which more than 100 have been confirmed. A few of these exoplanets resemble the Earth in size or mass.

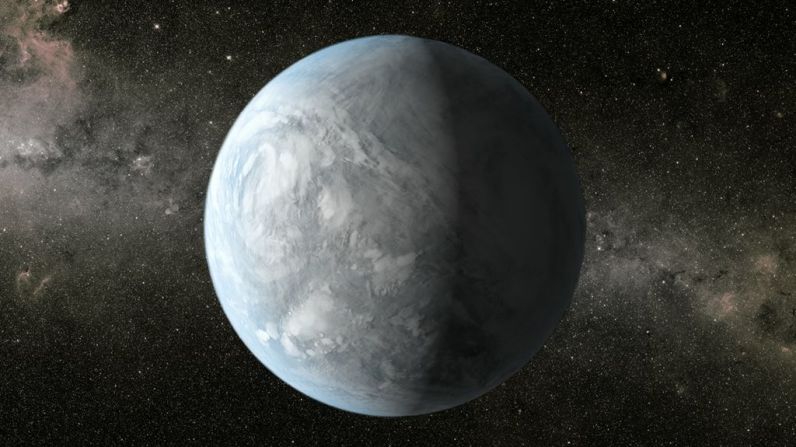

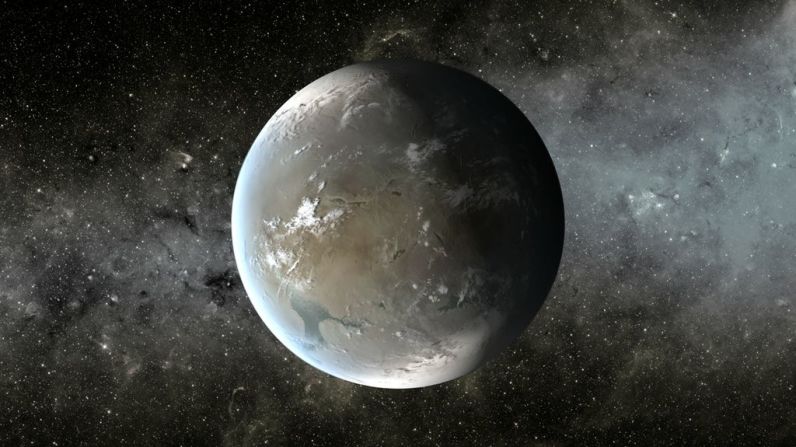

Recently, three Earth-like planets were even reported to be in the habitable zone: close enough to the star they orbit that water is liquid, yet not so close that it is boiling. Planets with liquid water may well harbor life.

Now, the second of four of the Kepler spacecraft’s reaction wheels, which aim the vessel’s instruments, appears to have failed. It remains to be seen whether full repairs are possible.

For the spacecraft to point accurately, at least three reaction wheels are needed, corresponding to the three dimensions (up-down, north-south, east-west). The fourth wheel serves as a backup and provides cross-comparisons of data among the wheels. The first wheel failed last summer; now Kepler has too few reaction wheels to keep pointing with sufficient stability.

When a major component like a thruster fails on any spacecraft, operations software points the craft’s solar panels toward the sun to ensure a continuous power supply.

Power is a satellite’s lifeblood: Lose it and you lose communications, so the satellite can’t be oriented properly or take data. Backup batteries allow the solar panels to be misdirected for a few hours or so, before all power is lost. But batteries drain quickly, so engineers design software to make sure that when something goes wrong, the spacecraft points in a direction that preserves power.

Urry: Three more homes for life in the universe?

Reaction wheels are spinning flywheels that carry “angular momentum,” a term roughly analogous to the force that keeps a car coasting even when the driver’s foot is off the gas.

Spinning objects keep spinning unless they transfer angular momentum to another object. For example, if a flywheel is commanded to spin more slowly (through an electric motor), the spacecraft will pick up spin to compensate. If the flywheel spins faster, the spacecraft will spin in the opposite direction. Increasing or decreasing the spin of a reaction wheel is therefore a way of pointing the spacecraft.

This may sound like a complicated way to make a telescope move, but the problem is, there is nothing in empty space to push on. To close a door, you push on it. This works because gravity holds you firmly on the ground, and your feet stay put because of friction with the floor.

If you pushed on an open door in space, it would push you in the opposite direction. In space, there is no standing still. So Kepler’s reaction wheels are essential for pointing the spacecraft accurately and steadily.

Unfortunately, less stable pointing means less accurate photometry (the measurement of light from the star). Since Kepler finds planets by measuring the tiny dips in a star’s brightness when a dark planet moves across the face of that star, less accurate photometry means Earth-like planets will be too hard to find.

Urry: A meteor and asteroid – 1 in 100 million odds

NASA is trying to figure how to fix or work around the broken reaction wheels. It has done amazing things before; you don’t have to be an optimist to think there is still a chance to turn Kepler around.

But the loss of a fully functional Kepler would be terrible. It has found more potential planets than any other facility or method. Kepler data have yielded an estimate of the total number of Earth-like planets in the Milky Way galaxy: at least 17 billion. That’s an Earth-like planet around one in every six stars.

Fortunately, there are other ways to find planets than by detecting transits (the passage of a planetary body across a sun), as Kepler does. In fact, the first few hundred exoplanets were found by the “radial velocity” technique, which detects tiny motions of a star as it and its planets orbit one another.

A Yale astronomy professor, Debra Fischer, has pioneered clever improvements to this technique so that she can find 100 Earth-size planets, perhaps 10% of which might harbor life. (Hear the full story in Fischer’s TEDx talk, “Why We Need to Find 100 Earths.”)

Fischer is going after Earth-like planets in the habitable zone. After all, the discovery of life on another planet would cause a profound shift in our world view, akin to the Copernican shift from an Earth-centric to a Sun-centric world.

So when Fischer says we should be “the alien civilizations that explore other worlds,” I say: With Kepler or without, it’s only a matter of time until we find signs of life on other worlds.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

Read more space and science news at CNN Light Years

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Meg Urry.